Branding: Why Do They Buy?

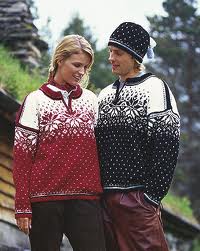

When I lived in Stockholm, I was responsible for customers throughout Scandinavia. One of my favorite customers was Dale of Norway, the creators of richly patterned, thick wool sweaters. The sweaters are very popular with winter sport enthusiasts in my home state of Colorado. They’re stylish and they’re practical … and therein lies a tale.

I visited Dale of Norway’s headquarters and met their CEO. The company is located in a picturesque little town called Dale. (We call it Dale as in Chip and Dale but the Norwegians pronounce it Darla). When I met the CEO I mentioned that I was from Colorado and that my wife and I were both customers. The conversation went something like this:

CEO: “Let me guess. You have one sweater and your wife has three.”

Me (surprised): “Yes. How did you know?”

CEO: “Women see our sweaters as fashion statements and they’re willing to buy more than one. Men see them as a high quality product that will last a life time. If it will last a life time, why would you ever buy more than one?”

Me: “I wish I understood my customers as well as you understand yours.”

There are a couple of lessons here. First, sometimes a satisfied customer is just that: satisfied. I was a very satisfied Dale of Norway customer. If you did a customer satisfaction survey, I would be right at the top. But I was generating exactly zero revenue for the company.

One of Dale of Norway’s challenges was to overcome the satisfied customer curse. They needed to give me (and even my wife) more reasons to buy. To complement their heavy weight sweaters, they introduced two new product lines — mid-weight sweaters and lighter weight accessories. I’m now the proud owner of a mid-weight sweater and some long underwear. I’m still satisfied but, more importantly, I’ve generated new revenues for Dale of Norway.

The second lesson: different people buy for different reasons. Don’t ever assume that what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. To the maximum extent possible, live with your customers. When you see the world through their eyes, you’ll find that different groups see your product differently. There’s nothing surprising in that — it’s just segment marketing. Unless you understand how each segment thinks, you’ll never communicate effectively with them. One message does not fit all.

The third lesson? Dale of Norway makes great sweaters, gloves, mittens, and scarves. So get out there and buy one … or two … or three. You can find them here.

Does Money Matter? (Part 1)

In the Citizens United case in 2010, the Supreme Court effectively removed all constraints on spending for political advertising. The Supremes argued — in a 5-4 decision – that the First Amendment prohibits the government from restricting free speech or, by extension,  from spending money to speak freely. For all practical purposes, this means that corporations, unions, and just plain rich people can spend as much as they want to promote a candidate or a cause.

from spending money to speak freely. For all practical purposes, this means that corporations, unions, and just plain rich people can spend as much as they want to promote a candidate or a cause.

As a result, we’ve seen a tidal wave of money — and a few bizarre billionaires — injected into this year’s presidential campaign. My question is: does it matter?

I come from the tech world and I can think of many examples where a small, poorly funded company took on a well-entreched giant and ate not only their lunch but also their breakfast and dinner. Think of SUN Micro versus IBM. Or Google versus Microsoft. In the political world, the Arab Spring revolts in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt suggest that money (and even coercion) can’t stop a good idea once it starts spreading.

I’ve also seen many expensive promotional campaigns that yielded little or nothing. A recent example from the tech world is Nokia’s big push for the Lumia 900 smart phone. A massive promotional campaign yielded minimal sales. (Anybody remember the Lumia 900?) A well-documented example in the political world was George Bush’s big push in 2004/5 to partially privatize Social Security. Bush launched a well-funded, well-coordinated nationwide campaign and spoke on at least 65 occasions to promote the idea. The more he spoke, the less popular the idea became. (I have an article in the works on this topic).

I see a big difference between changing your mind and changing your values. (In fact, this is a major insight of classical rhetoric). I don’t think many people will change their values just because they see a 30-second commercial. An angry commercial may activate people (and that’s important) but I don’t think it will change people. In fact, an angry and cynical ad may push people in the opposite direction. I’ll discuss reasons for this in my next article.

Of course, if I were running a political campaign, I would prefer to have more money than my opponent. But money isn’t everything. For instance, I’ve worked for small companies battling against larger companies for my entire career. I wouldn’t say that all my adventures ended happily but many of them did.

So, will the massive spending in the 2012 election affect the outcome? It’s a grand experiment. One possible — perhaps probable — outcome is that we’ll get to November 7 and find the politicos saying, “Wow, we just spent a massive amount of money and it had no impact whatsoever. There must be a better way to spend our money.” If that happens, the 2016 election will be a lot more pleasant.

(Speaking of 2016, what do you think? Condoleezza versus Hillary?)

How to Be a Team Player While Saying “No”

You’re a team player. You like to help your teammates. You like to say “yes”. But you also like to deliver results. You hold yourself accountable for fulfilling your commitments. You like to under-promise and over-delvier.

You’re a team player. You like to help your teammates. You like to say “yes”. But you also like to deliver results. You hold yourself accountable for fulfilling your commitments. You like to under-promise and over-delvier.

Let’s say that you have a mountain of work to attend to. You’ve made lots of commitments and now you’re trying to fulfill them. You’re working hard and making progress. Then somebody (who outranks you) asks you to take on another major project. Saying “yes” to the new project means that you won’t be able to fulfill your commitments on existing projects. So how do you say “no” without letting the team down? Just watch the video.

90 Days of Anger

What’s wrong with people laughing? The short answer: they just want to go on laughing. That’s good for teaching but not good for politics.

People love to laugh. If you’re trying to persuade an audience to your way of thinking, it’s good to get them to laugh. They’ll trust you more and, more importantly, they’ll think, “Oh good, she’s funny. Maybe she’ll tell some more jokes.” If they’re anticipating more jokes, the audience will pay more attention. You can get your point across more easily because the audience is primed and attentive. (By the way, this doesn’t work if you tell lame jokes. You have to tell funny jokes).

So why is this bad for politics? Because in political speeches, you’re aiming to motivate people and humor doesn’t motivate. People who are laughing just want to go on laughing. They don’t want to canvas neighborhoods, call friends, give money, storm the barricades, or even get off the sofa to vote.

The emotion that motivates is anger. That’s why political speeches and advertisements are so angry. The politicians want you to do something. Making you angry (and scared) is the simplest way to accomplish their objective. Making you laugh is counter-productive.

In rhetorical terms, the simplest way to make an audience angry is a technique known as “attributed belittlement”. You tell the audience that your opponent (or competitor) belittles them. “They don’t respect you. They think they’re superior to you. They think they have the right to tell you what to do, because you’re dumb. They’re elite and you’re not.” Sound familiar? No one likes to be belittled, so this is a very effective technique. (I’ve used it myself in commercial competition and it works).

So what can you expect in the 90 days leading up to the presidential election in the United States? A flood of angry messages and, more specifically, a tidal wave of attributed belittlement. If you’re like me, you’ll just want to tune out the whole mess.

This is a different kind of communication than I normally teach. I usually focus on “deliberative” presentations — you present a logical argument and the audience deliberates on it. A political presentation is usually a “demonstrative” presentation — you’re demonstrating solidarity and group loyalty, partially by demonizing the opposition. There’s no need for logic. You can learn more about deliberative and demonstrative presentations here.

Does your e-mail address say you’re a psychopath?

The first thing I know about a person is often their e-mail address. From that small scrap of information, I start building an image of what the person is like. If you think first impressions are important, think about what your e-mail address says about you. Your e-mail address is often the first element of your personal brand.

The first thing I know about a person is often their e-mail address. From that small scrap of information, I start building an image of what the person is like. If you think first impressions are important, think about what your e-mail address says about you. Your e-mail address is often the first element of your personal brand.

Some people use their e-mail addresses to identify their hobbies or interests, like bookworm@xyz.com or bikerbob@wxy.com. But I’m usually more interested in the information after the @ sign. If I receive an e-mail from an @aol.com address, I think the sender is over the hill and out of date. If it comes from a cable company (e.g. @comcast.net), I think they’re not very technically astute. If they change cable companies, they’ll have to change their e-mail address as well. How boring!

I thought I might be alone in these perceptions so I was interested to learn that no less an authority than the New York Times‘ David Pogue has similar biases. In an article in yesterday’s Times, Pogue introduced Microsoft’s new e-mail service. In passing, Pogue referred back to Microsoft’s previous service, Hotmail. Pogue writes that, “Even today, a Hotmail address still says ‘unsophisticated loser’ in some circles.”

For these reasons, I was deeply disappointed when Apple tried to shift its e-mail service from @mac.com to @me.com. My e-mail address has long been a variant of myname@mac.com. Part of my personal brand is that I use a Mac. It’s OK with me if people know that. Maybe they’ll think that I “think different”. When Apple changed it to me.com, I was horrified. In my humble opinion, anyone who uses an e-mail address of myname@me.com is self-centered at best or a psychopath at worst. Even if I think “it’s all about me” (and I do sometimes), I don’t want to project it in my personal brand. Thankfully, I can still use @mac.com designation and I hope I always will.

I teach my students that they need to think about their personal brand. It’s important for getting a job or a promotion. Your brand is a combination of how you behave, how you speak, how you dress, and so on. Each of those sends clues about who you are and whether you’d be good teammate or not. When you think about your brand, begin at the beginning — your e-mail address.