Computers Are Useless. They Only Give You Answers.

I’ve worked with some highly creative people during my career. I’ve also worked with very insightful thinkers, both in business and in academia. Oftentimes, the two skills overlap: creative people are also insightful thinkers and vice-versa. I’ve often wondered if creativity leads to insight or if insight leads to creativity. Lately, I’ve been thinking that there’s a third factor that produces both — the ability to ask useful questions.

I’ve worked with some highly creative people during my career. I’ve also worked with very insightful thinkers, both in business and in academia. Oftentimes, the two skills overlap: creative people are also insightful thinkers and vice-versa. I’ve often wondered if creativity leads to insight or if insight leads to creativity. Lately, I’ve been thinking that there’s a third factor that produces both — the ability to ask useful questions.

Indeed, the title of today’s post is a quote from Pablo Picasso, who seemed both creative and insightful. His point — computers don’t help you ask questions … and questions are much more valuable than answers.

So, how do you ask good questions? Here are some tips from my experience augmented with suggestions by Shane Snow, Gary Lockwood, Penelope Trunk, and Peter Wood.

It’s not about you — too often, we ask long-winded questions designed to show our own knowledge and erudition. The point of asking a question is to gather information and insight. Be brief and don’t lead the witness.

You can contribute to a better answer — even if you ask a great question, you may not get a great answer. The response may wander both in time and logic, looping forward and backward. You can help the respondent by asking brief, clarifying questions. Don’t worry too much about interrupting; your respondent will likely appreciate your help.

Remember your who, what, where, when, how … and sometimes why — these words introduce open-ended questions that often result in more information and deeper insights. Be careful with why. Your respondent may become defensive.

Don’t go too narrow too soon — decision theory has a concept called premature commitment. We see a potential solution and start to pursue it while ignoring equally valid alternatives. It can happen in your questions as well. Start with broad questions to uncover all the alternatives. Then decide which one(s) to pursue.

Dumb questions are often the best — asking an (open-ended) question whose answer may seem obvious often uncovers unexpected insights. Even if you’re well versed in a subject, don’t assume you know the answer from the respondent’s perspective. He or she may have insights you know nothing about.

Be aware of your ambiguities — even simple, seemingly straightforward questions can be ambiguous. Your respondent may answer one question when you intended another. Here’s a simple example: what’s the tallest mountain in the world? There are two “correct” answers: Mt. Everest (if you measure from sea level) or Chimborazo (if you measure from the center of the earth). Which question is your respondent answering?

Think of parallel questions — I’m reading a Kinsey Millhone detective novel (U is for Undertow). One of the important questions Kinsey asks herself is, “why were the teenage boys burying a dog?” It gets her nowhere. But a slight tweak to the question — “Why were the boys burying a dog there?” — provides the insight that solves the mystery. (Reading detective novels is a good way to learn questioning techniques).

Clarify your terms — my sister is an entomologist. She knows that there’s a difference between a bug and an insect. I use the terms more or less interchangeably. If I ask her a question about bugs, she’ll answer it in the technical sense even though I mean it in the colloquial sense. We’re using the same word with two different meanings. It’s a good idea to ask, “When you talk about bugs, what do you mean?”

Think about how you answer questions — when you respond to questions, observe which ones are annoying and which ones lead to interesting insights. Stockpile the interesting ones for your own use.

Silence is golden — when speaking on the radio, I might say “over” to indicate that I’m finished speaking and it’s your turn. In normal conversation, we use body language and tone-of-voice to make the same transfer. Breaking the expected etiquette can lead to interesting insights. You ask a question. The respondent answers and turns it back to you. You remain silent. There’s an awkward pause and, often, the respondent continues the answer … in a less rehearsed and less controlled manner. Interesting tidbits may just spill out.

Don’t be too clever — Peter Wood probably says it best, “A few people have a gift for witty, memorable questions. You probably aren’t one of them. It doesn’t matter. A concise, clear question is an important contribution in its own right”.

Will Sweden Ever Build a Las Vegas? Not On Your Lagom.

Suellen and I lived in Stockholm for three years and generally loved it. The winters are long and dark but the people are sunny and positive. Taxes are high but services are great. And they write some of the best murder mysteries in the world. Here are some things we’ve found out about Sweden, Scandinavia (Sweden, Denmark, and Norway) and the Nordic countries (Scandinavia plus Iceland and Finland).

They’re innovative — Sweden produces more patents per capita than any other country. Finland is second; Denmark is sixth. The U.S is ninth. In the Bloomberg Survey of Innovative Countries, the U.S. is first. Finland in fourth; Sweden is fifth; Denmark is ninth.

They’re happy — The Danes are the happiest people in the world. Finland is second; Norway is third; Sweden is seventh. The U.S. is 11th.

They’re free (from prison) — Sweden has about 70 people in prison per 100,000 population. The U.S. has 700.

Women are close to equal — Sweden is widely considered the best place in the world for a woman to pursue a career. Iceland usually ranks first in surveys of overall gender equality. Even in the Nordics, however, men still make more money than women.

They’re healthy — On the Bloomberg Survey of the World’s Healthiest Countries, Sweden ranks ninth. Finland is 22nd and Denmark is 26th. The U.S. is 33rd.

They get great vacations — typically six weeks of paid vacation plus various national holidays. If you want to take four weeks in a row, your company is obligated to permit it.

They’re egalitarian — the Nordic countries rank among the most egalitarian in the world in most measures of income distribution.

They’re well governed — according to The Economist‘s ranking of the best governed nations in the world, the top four are: Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Norway. The U.S. is eighth.

What explains all this? I think some of it is the Swedish concept of lagom. We have no equivalent word in English but lagom is usually translated as “just enough” or “just the right amount, not too much”. Here are two examples:

The Swedish soccer (football) team played another nation and won by a score of 5 to 0. The Swedish coach worried aloud, saying, “I wish we had won by 2 to 0. We humiliated them. It’s not lagom. They’ll be looking for revenge the next time.” Have you ever heard any coach, anywhere in the world wishing they had won by less?

Suellen got into a long conversation with some Swedish friends about public education. Somehow, the subject of special programs for gifted and talented kids in the U.S. came up. The Swedes were dumbfounded. “Why on earth,” they asked, “would you invest extra money to help kids who already have all the advantages? If they’re so gifted and talented, they’ll figure out how to succeed.” The Swedish way would be to invest more in kids who are below the norm to help them come up to the middle. That’s lagom.

Could lagom explain Sweden’s (and the Nordics’) successes? Probably not all of them. But it does provide a sense of balance and fair play that lubricates the country’s society and economy. It also prompts a questioning attitude — Why are we doing what we’re doing? What does it lead to? What do we hope to achieve? The answer is not just more. It’s more balance. Perhaps that’s why this week’s issue of The Economist claims that Sweden is leading a “quiet revolution”, “thinking the unthinkable”, and fundamentally re-inventing capitalism. It’s a great read — just click here.

Social Media for Business Leaders

As a marketing guy, I understand (sort of) the marketing aspects of social media. If you can start a conversation — and keep it interesting — you can engage your market in ways that are impossible with “interruption marketing”. You can exchange ideas, gather suggestions, support charities, and engage in positive social activities. Along the way, you can mention your products. You offer something of interest (or utility) and the products tag along for the ride.

As a marketing guy, I understand (sort of) the marketing aspects of social media. If you can start a conversation — and keep it interesting — you can engage your market in ways that are impossible with “interruption marketing”. You can exchange ideas, gather suggestions, support charities, and engage in positive social activities. Along the way, you can mention your products. You offer something of interest (or utility) and the products tag along for the ride.

But social media is not just about marketing. Executives should be able to use social media to enhance both internal and external communication. Yet, I haven’t found many examples in the literature. Fortunately, McKinsey just published an interesting case study based on GE’s experience. The authors, who are GE leaders themselves, point out that GE is not a “digital native” and its experiences may, therefore, be relevant to a wide range of organizations. They then outline six social media skills that all leaders need to learn. The first three are personal; the last three are strategic or organizational.

Producer — creating compelling content. Digital video tools are now widely available and easy to use. Even busy senior executives can weave them into their communications. As compared to traditional top-down communications, the emphasis shifts from high production quality to authenticity. The goal is to invite participation and collaboration. Speaking plainly and telling stories in an authentic voice invites participation much better than a highly produced video.

Distributor — leveraging dissemination dynamics. Instead of sending a message and expecting it be consumed, you now send a message and expect it to be mashed up. A successful social message will be picked up by people at all levels of the organization, commented on, “recontextualized”, and forwarded along. You want this to happen which means giving up a significant amount of control — not always an easy concept for executives. You also want to build up a followership within the organization long before you need it.

Recipient — managing communication overflow. We’re already drowning in information. Why take on social media? Because it’s more credible than top-down media. By learning to use filters effectively, you can also use social media to manage the flow of information to and from your desk. You should practice when and how to respond to postings and tweets. You don’t need to respond frequently but you do need to respond thoughtfully.

Advisor and orchestrator — driving strategic social media utilization. Fundamentally, executives need to promote the use of social media and guide it to maturity. Your company may be enthusiastic but inexperienced. Or you may have leaders who wish to avoid it altogether. A good leader can harness the enthusiasm of “digital natives” and even use them as “reverse mentors” to build capabilities within the organization.

Architect — creating an enabling organizational infrastructure. On the one hand, you want to encourage collaboration and free exchange. On the other hand, you need some rules. It helps if you have well-established values of integrity, collaboration, and transparency. If your company hasn’t established these values, it’s time to get started. Social media will arise in your organization whether you’re ready or not.

Analyst — staying ahead of the curve. As your organization masters social media, something new will emerge. Perhaps, it’s the Internet of Things. As I’ve noted before, this could help us reduce health care costs. It could also have huge implications for your organization — both good and bad. Better stay awake.

And what do you get if your company’s leaders master these skills? The authors say it best: “We are convinced that organizations that … master … organizational media literacy will have a brighter future. They will be more creative, innovative, and agile. They will attract and retain better talent, as well as tap deeper into the capabilities and ideas of their employees and stakeholders.”

Want to Be More Innovative? Move to Boulder. Or Sweden.

In an earlier post, I pointed out that cities generate much more than their “fair” share of innovations. The reason is simple: there’s more opportunity to run into new ideas, concepts, and people. It turns out that innovation is even more concentrated than I thought. Just 20 of the America’s 370 metropolitan statistical areas — accounting for 34% of the population — produce 63% of the nation’s patents. The top five patent-producing metropolises in the U.S. (in order) are: San Jose, CA, Burlington, VT, Rochester, MN, Corvallis, OR, and Boulder, CO. These areas account for 12% of the U.S. population but 30% of American patents.

In an earlier post, I pointed out that cities generate much more than their “fair” share of innovations. The reason is simple: there’s more opportunity to run into new ideas, concepts, and people. It turns out that innovation is even more concentrated than I thought. Just 20 of the America’s 370 metropolitan statistical areas — accounting for 34% of the population — produce 63% of the nation’s patents. The top five patent-producing metropolises in the U.S. (in order) are: San Jose, CA, Burlington, VT, Rochester, MN, Corvallis, OR, and Boulder, CO. These areas account for 12% of the U.S. population but 30% of American patents.

The finding comes from a new Brooking’s Institute report on patents. Some other highlights:

- The pace of patenting in the U.S. continues to climb. The growth of patent applications slowed after the IT bubble burst but is now at an all time high.

- Though the pace has increased, the U.S. ranks ninth in the world in terms of patents per capita. The countries ahead of the U.S are (in order): Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, Israel, the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, and Japan. (Those pesky Scandinavians are at the top again).

- The average patent is worth about $500,000 in direct market value — and much more as it diffuses through the economy.

- The last period of great patent growth in the United States fell between the Civil War and the early 20th century. We “democratized” invention during that period — with many patents coming from blue-collar workers who were not professional researchers. Today, patents are more complicated, more difficult and expensive to obtain, and require more education. The ability to create patents is concentrated in fewer organizations in fewer places.

- The price per patent is rising in the U.S.. From 1953 to 1974, $1.8 million in R&D spending generated one patent. Since 1975, the cost has been $3.5 million (in inflation adjusted dollars).

- Almost half (48%) of the patents granted in the U.S. from 2006 through 2010 could be grouped into the Big Ten categories: Communications, Computer Software, Semiconductors, Computer Hardware, Power Systems, Electrical Systems, Biotech, Measuring & Testing, Information Storage, Transportation. The top five categories account for slightly more than 30% of all patents.

- Patent ownership has become broader and more competitive. Of the top ten patent producing companies from 1976 to 1980, only four were in the top 10 in 2011-2012: IBM, GE, GM, and AT&T.

- The federal government dominated R&D spending up to approximately 1970. By the late 1970s, the federal government share fell below half. In 2009, the government share of R&D spending was about one-third. Roughly 60% of federal R&D spending goes to private companies, 30% goes to universities (including university-administered national labs).

- Metropolitan areas that lead in patent production also lead the nation in terms of of productivity growth. They also enhance local employment opportunities and generate a disproportionate number of initial public offerings (IPOs).

The Brooking Report provides ample evidence that the research and innovation that lead to patents has a dramatic impact on local economies, employment, and growth. Bottom line: if you want your city to grow, don’t build a football stadium. Build a research university. Or move to Boulder.

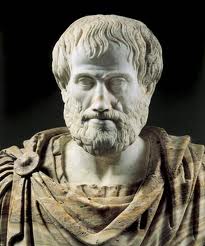

Aristotle, HBR, and Me

I love it when the Harvard Business Review agrees with me. A recent HBR blog post by Scott Edinger focuses on, “Three Elements of Great Communication, According to Aristotle“. The three are: ethos, logos, and pathos.

Ethos answers the questions: Are you credible? Why should I trust your recommendations? Logos is the logic of your argument. Is it factual? Do you have the evidence to back it up? (Interestingly, the more ethos you have,the less evidence you need to back up your logos. People will trust that you’re credible). Pathos is your ability to connect emotionally with your audience. If you have high credibility and impeccable logic, your audience might conclude that you could take advantage of them. Pathos reassures them that you won’t — your audience knows that you’re a good citizen.

When I teach people the arts of public speaking, I generally recommend that they start by establishing their credibility (ethos). The trick is to do this without overdoing it. If you come across as a braggart, you reduce your credibility rather than burnishing it. A good tip to remember is to use the word, “we” rather than “I”. “We” implies teamwork; “I” implies an egocentric psychopath.

After establishing your credibility, you proceed to the logic (logos) of your argument. What is it that you’re recommending and why do you think it’s a good solution for the audience’s needs? It’s often a good idea to start by defining the audience’s needs. Then you can fit the recommendation to the need. Keep it simple and use stories. Nobody remembers abstract logic and difficult technical concepts. They do remember stories.

Think about pathos both before the speech and in the conclusion. Ideally, you can meet the audience before your speech, ask insightful questions, and make personal connections. The more you can talk to members of the audience before the speech, the better off you’ll be. Look for anecdotes that you can use in your speech — that also builds your credibility. If nothing else, spend the last few minutes before your speech shaking hands with audience members and thanking them for coming to your speech. At the end of your speech, you can return to similar themes and express your appreciation. It’s also appropriate (usually) to point out how your recommendation will affect members of the audience personally. For instance, “We believe that our solution will help your company be more efficient. It will also help you build your career.”

Those of you who have followed my website for a while may remember my videos on ethos, logos, and pathos. I made them when I worked at Lawson Software and was teaching communication skills internally. Again, I’d like to thank Lawson for allowing me to use these videos on this website as I build my own practice.

By the way, all these suggestions apply to deliberative speeches. You present a logical argument and ask your audience to deliberate on it. On the other hand, you can also give a demonstrative speech where you throw the logic out altogether. They’re often called barn burners or stem winders. You can learn more here.