Chris Christie: The I Guy

Me, myself, and I

In my video, Five Tips for the Job Interview, my first tip is to be careful how often you say “I” as opposed to “we”. If the company you’re interviewing with is looking for team players — and many companies say they are — then saying “I” too often can hurt your chances. You can come across as self-centered and egocentric. Someone, in other words, who doesn’t play well with others.

I thought about this tip the other day when I watched Chris Chrstie’s press conference addressing the bridge closure scandal. (If you haven’t heard about it, you can get a good summary here). As the Republican governor of a very Democratic New Jersey, Chritsie is widely regarded as an appealing candidate for the Republican nomination for president in 2016. In a way, he’s interviewing for the biggest job of all. Perhaps he should have watched my video.

In the press conference, Christie needed to address a scandal that appears to be about naked political payback. The Democratic mayor of Fort Lee, New Jersey didn’t endorse Christie for governor in the recent campaign. As a result (it appears), Christie’s minions shut down traffic in Fort Lee for four days. Christie needed to apologize and distance himself from such nasty political deeds.

Dana Milbank, a columnist for the Washington Post, paid close attention to the press conference. In fact, he went through the transcript and analyzed Christie’s language. The press conference lasted 108 minutes; Christie said some form of “I” or “me” (I, I’m, I’ve, me, myself) 692 times. That’s 6.4 times per minute or a little more than once every ten seconds.

The net result is that Christie comes across as an egomaniac. That may be the case but, generally, you don’t want to come across that way in an important interview. There’s a lot that I like about Governor Christie — he seems to be one of the few politicians in America who can actually pronounce the word “bipartisan”. I hope he can learn to pronounce “we” and “you” as well.

Good News on Dementia?

Harriet speaks to the future.

My mother-in-law, Harriet, is a delightful nonagenarian who is still as sharp as a tack. What’s the secret to her mental acuity? I’m willing to bet that the fact that she’s an avid bridge player has something to do with it.

Indeed, Harriet may be a leading indicator of the changing shape of the dementia demographic. Conventional wisdom holds that our health care system is about to be overwhelmed as the baby boom ages and sinks into dementia.

The logic is straightforward. Major premise: Old age is the leading risk factor for dementia. Minor premise: People are living longer. Conclusion: Everybody will become demented sooner or later and our health care system will collapse.

In the current issue of New Scientist, however, Liam Drew reports on new research that suggests that Harriet may be an emblem of change, not an exception to it. As Drew points out, the conventional wisdom “… is based on the assumption that people will continue to develop dementia at the same rate as they always have.” Drew then reports on two studies that suggest this assumption is no longer true (if it ever was).

The first is a research report from the Lancet that compares two dementia censuses conducted 20 years apart in three regions the U.K. The first census, conducted in 1994, counted 650,000 people with dementia. In 2013, the researchers repeated the study and, assuming that the dementia rate held steady, projected that they would find 900,000 people with dementia. Instead, they found about 700,000. The report concludes that, “Later-born populations have a lower risk of prevalent dementia than those born earlier in the past century.”

The second study, conducted in Denmark, reached essentially the same conclusion. The research compared people born in 1905 with those born in 1915. Drew reports that, “While the two groups had similar physical health, those born in 1915 markedly outperformed the earlier-born in cognitive tests.”

So, what’s going on? Well, for one thing, we’re taking better care of our hearts. In general, healthier hearts provide better circulation. More oxygen-rich blood reaches our brains, which probably improves brain health. A heart healthy lifestyle may also be a brain healthy lifestyle.

Another theory is cognitive reserve, which suggests that we may be able to make our brains more resilient and resistant to damage. In other words, the brain is not just a “given”; it can be developed in much the same way that a muscle can. As Wikipedia puts it, “Exposure to an enriched environment, defined as a combination of more opportunities for physical activity, learning and social interaction, may produce structural and functional changes in the brain and influence the rate of neurogenesis … many of these changes can be affected merely by introducing a physical exercise regimen rather than requiring cognitive activity per se.”

What creates cognitive reserve? Educational attainment seems to play an important role. Physical and social activity also seem to contribute. I can’t help but wonder whether playing bridge – which combines social and cognitive elements – might not be the perfect way to build our cognitive reserves.

Over the years, we’ve all learned a lot from Harriet. She’s smart and she’s wise. And she may just have taught us how to live intellectually rich lives for many years to come. Thank you, Harriet.

Design As A Competitive Weapon

Design thinking

When we think of design, we often think of things. We can design a phone, a car, a coffee maker, or a house. We can make them simple or complex or modern or traditional but, ultimately, it’s a thing, a physical object.

Many business and organizational leaders are now arguing that we’re thinking too narrowly when we define design as for-things-only. Roger Martin, the former Dean of the Rotman School of Management, sums it up nicely, “…everything that surrounds us is subject to innovation – not just physical objects, but political systems, economic policy, the ways in which medical research is conducted, and complete user experiences.”

Two things, in particular, attract me to design thinking:

It starts with a solution – in design thinking, we first imagine what could be. Then we work backwards. What might a solution look like? What would it need to include? Who would need to be involved? Many business leaders start with the problem and focus on what went wrong. Design thinkers focus on the solution and what could go right. It’s a refreshing change.

It includes both the rational and irrational – I studied a lot of economics and I was always a bit uncomfortable with the starting assumption: we’re dealing with economically rational individuals. But are we really economically rational? The whole school of behavioral economics (which evolved after I graduated) says no. As Paola Antonelli points out, design thinking involves “the complete human condition, with all of its rational and irrational aspects….”

In past articles (here, here, and here), I’ve followed Paul Nutt’s lead and written about decision-making that leads to debacles. I’ve recently re-analyzed Nutt’s case studies of several dozen debacles and – as far as I can tell – none of them used design thinking. The debacles resulted from classic decision-making processes driven by successful business executives. Would those executives have done better with design thinking? It’s hard to say but they could hardly have done worse.

Is design thinking superior to classic business decision-making? The absence of design-driven debacles in Nutt’s sample is suggestive but not definitive. Are there positive examples of design-driven business success? Well, yes. In fact, close readers of this website may remember Roger Martin’s name. He was the “principal external strategy advisor” to A.G. Lafley, the highly lauded CEO of Procter & Gamble. According to a report from A.T. Kearney, “During Lafley’s tenure, sales doubled, profits quadrupled, and the company’s market value increased by more than $100 billion”.

Does one success – and the absence of debacles – prove that design thinking is superior to classic business thinking? No … but it sure is intriguing. So, I’m trying to unlearn years of system thinking and teach myself the basics of design thinking. As I do, I’ll write about design thinking frequently. I hope you’ll join me.

(By the way, the quotes from Roger Martin and Paola Antonelli are drawn from Rotman on Design: The Best Design Thinking From Rotman Magazine, which I highly recommend).

I Still Speak Southern

Do I sound like Rhett?

When people ask me where I’m from, I often respond by saying, “I’m from the Air Force”. As a military brat, I bounced around a lot and mainly grew up on or around Air Force bases. I didn’t develop a strong attachment to any one place. I didn’t feel like I was “from” Nebraska – where I was born at Offutt Air Force Base. Nor did I feel like I was from any of the other bases we stopped at along the way.

People sometimes ask me where I’m from because they can’t place my accent. It’s an Air Force accent and, as such, it’s fairly neutral. Since the early 19th century, however, my family has lived in Texas, which certainly has a unique accent and a number of Spanish/Indian/Anglo/Texas regionalisms. You’re probably from Texas if you know who’s in the hoosegow. Or who the original Travis was. Or what a Comanche moon is.

I’ve lived in Colorado since the mid-seventies and I’ve always assumed that my Texan-ness was thoroughly washed away. After all, I never lived in Texas so I must have inherited any Texanisms in my vocabulary from my parents and grandparents. Since they’re long gone, I assumed my Texansims were, too. I thought I spoke more like a Coloradan than a Texan.

It turns out that I was wrong. It’s not my accent that gives me away as a son of the south. Rather, it’s my word choice. Even after all these years, I still use regional words to describe people, things, and activities.

I discovered this by taking a quiz on regional dialects in the New York Times. (You can find it here). The quiz asks 25 questions about the words you use and how you pronounce them. For instance, one question is “What do you call a sweetened carbonated beverage?” Is it a coke, a pop, a soda, etc.? A question on pronunciation is: “How do you pronounce cot and caught?” Do you pronounce them the same way or differently?

I took the quiz and – much to my surprise – found out that I speak more like a person from east Texas or west Louisiana than like a person from Colorado. I was struck by the result and so I passed the quiz along to my online students, who are scattered all over the country. The students who took the quiz said it was spot on and could easily distinguish a Utahn from an Indianan from a Mississippian.

Regional accents may have evolved to help us identify who is like us and who is not. Who’s a friend and who’s a stranger? Who can be trusted and who needs to prove themselves? We’re so mobile in the United States (and we watch so much TV) that I thought most regionalisms had disappeared. It’s interesting to find that they haven’t. I wonder how that affects our politics, communication, and commerce.

It’s a topic worth studying and I hope you’ll take the quiz and let me know the results. In the meantime, I’ll just say that it’s been a real pleasure visiting for a spell and I hope I’ll see y’all again in the by and by. Oh, and be sure to bring your Momma and Daddy. I’d like to sit with them for a spell.

Groups Get It Wrong (All Too Often)

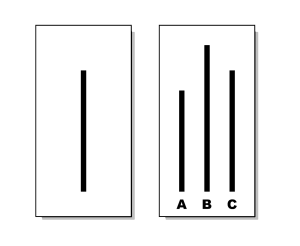

The right answer is obviously B.

Why do decisions go wrong? Many times, it’s because the decision is made by a group, not by an individual. Individuals tend to look at the evidence and make a decision. It may not be the right decision but it’s often based on an assessment of the facts.

Groups may assess the facts as well but they also assess the politics of the situation. The issue may be decided on group dynamics rather than a dispassionate review of the evidence.

Bain & Company recently published a white paper (Decision Insights: How Group Dynamics Affect Decisions) that provides a useful summary of the issues. Here are four ways, for instance, that group dynamics can lead to debacles.

Conformity – if you’re a team player, you may go with the team’s decision even if you realize it’s wrong. The graphic above shows Solomon Asch’s classic experiment. Which line – A, B, or C – is the same length as the line to the left? Working alone, you’ll probably figure out that C is the right answer. However, if you’re in a group that says B is the right answer, you’re quite likely to go with the group. Many companies say they want team players, but they need to be aware of the implications. (See also Group Behavior – The Risky Shift.)

Group Polarization – let’s assume for a moment that you belong to a politically conservative group. You talk to conservatives regularly. Indeed, you talk only to conservatives. You reinforce each other and the group gets more and more conservative. In many cases, the group becomes more conservative than any of its individual members. (See also, Will The Internet Cause Dementia? and Where You Stand Depends on Where You Sit.)

Obedience to Authority – the quickest way to stifle innovation is to let the boss speak first. We all want to please our bosses, so if the boss expresses a preference for X over Y, we often begin to find reasons why X is indeed better than Y. It’s hard to argue with your boss … unless you’re specifically asked to play the role of devil’s advocate, which is often a good idea. Note to bosses: keep quiet. (See also, Want A Good Decision? Go To Trial.)

Bystander Effect – when we’re not sure what to do, we often look to others to see what they’re doing. If they’re panicking, we get panicky. If they’re cool, calm, and collected, we calm down (even if we think we should panic). Individuals often understand a situation better than groups do which is why you should never have a heart attack in a crowd.

So, what to do? Diversity in a group often helps overcome groupthink and polarization, so pull people together from different backgrounds and risk profiles. Playing roles can help. You might stage a mock trial or ask someone to play the devil’s advocate. You can also ask each individual to write down his or her recommendation anonymously, put them all in a hat, and then discuss all of them. You can also prime the team by discussing what it means to be a team player. Emphasize the need to make the best decision, not just the most comfortable one.

And, if all else fails, just ask the boss to leave the room.