What’s Walking Good For?

I often ask my students a simple question: What were you doing the last time you had a good idea? Whatever they answer, I say: “Do more of that and you’ll have more good ideas.”

So what are they doing when they have good ideas? A fair number – often a majority – are walking. Taking a break and going for a walk stimulates our thinking in ways that produce interesting and novel ideas. Walking takes a minimum amount of conscious effort; we have plenty of mental bandwidth left for other interesting thoughts. Walking also provides a certain amount of stimulation. The sights and sounds and smells trigger memories and images that we can combine in novel ways. By moving our bodies slowly, we create thoughts that move much more quickly.

Going for a walk with a friend, colleague, or loved one can also help us create richer, deeper conversations. Walking stimulates novel thoughts; if a companion is beside us, we can share those thoughts immediately. The back-and-forth can lead us into new territory. A good conversation is not just an exchange of existing ideas. Rather, it produces new ideas – and walking can help.

Walking can also help us have difficult conversations. The key here may be our posture and proximity rather than walking per se. When we walk with another person, we are typically side-by-side, not face-to-face. We’re not confronting each other physically. We’re talking to the air, rather than at each other. We’re slightly insulated from each other, which makes it easier to both make and receive blunt statements.

According to Walk-And-Talk therapists like Kate Hays, walking can also enhance traditional psychotherapy sessions. Walking with a therapist “…spurs creative, deeper ways of thinking often released by mood improving physical activity.” Walking seems especially helpful when the conversation is between a parent and, say, a teenager. We feel close, but not intimidated. (Side note: we often describe deep conversations as “heart-to-heart” but rarely describe them as “face-to-face.”)

What else can walking do? It’s an “active fingerprint.” As the MIT Technology Review puts it, “… your gait [is} a very individual and hard-to-imitate trait.” In other words, the way you walk uniquely identifies you.

Clearly, we can use gait-based identification for positive or negative ends. With so many security cameras in place today, we’re rightly concerned about facial recognition as an invasion of privacy. But we can hide our faces with something as simple as a surgical mask. Disguising the way we walk is much more difficult.

On the other hand, think of a device – perhaps a smart phone – that can uniquely identify you based solely on your gait. You put your phone in your pocket and walk along; it “knows” who you are. Rather than depending on fingerprints or passwords, the device simply monitors your gait. One benefit is convenience – you don’t have to enter a password every time you want to use the device. The second benefit is perhaps more important: security. A thief could steal your password or even an image of your fingerprint. But could they imitate your gait? Probably not.

What else is walking good for? Oh, simple things like health, flexibility, weight loss, mental acuity, sociability, and so on. I’d like to hear your stories about the benefits of walking. Just send me an e-mail. I’ll read them after I get back from my walk.

Innovation & Sociology – Jobs To Be Done

Not to stay warm

Thirty years ago, I was a product manager for a startup company that created high-performance, multiprocessing minicomputers. Powerful, scalable, and based on open standards, they offered exceptional price/performance. In 1988, Electronics magazine gave its Computer of The Year award to the flagship model

As we introduced the system, we described the “ideal” customer: a medium to large organization that used Unix-based systems, and ran large database applications, especially Oracle applications. We trained the sales force, produced some modest direct mail campaigns, and launched.

Then reality set in. In the first three months, we sold about 45 machines to some 30 different organizations. We gathered data about our new customers and looked for correlations that would help us target prospective customers more precisely. We found nothing — no patterns in terms of size, SIC code, geography, application, and so on. The data were almost random.

We were stumped. So, we decided to interview the key decision maker in each account. We created an interview guide and fanned out to visit customers

After our visits, we dug into our findings. Again, we found no useful patterns in the demographic data. Then we started describing the key decision makers. Who were they? Why did they decide on us?

Most of the decision makers were men in their early thirties who had recently been promoted to a position typically described as VP, Data Processing. They replaced an older person who had held the same position for more than ten years. One of our marketers had a flash of insight: “It’s almost like the decision maker is saying, ‘I’m the new sheriff in town. We’re going to do things my way. This is one of my first big decisions … and we’re going to buy a hot new machine from a startup company. I’m going to make my mark.’”

It turned out to be a very accurate description. Nominally, our customers were buying our machines to run large applications. But psychology was perhaps more important. We estimated that roughly 60% of our customers fit the “new sheriff” profile.

We decided to market specifically to new sheriffs. We trawled through organization profiles and identified those that had a new VP of Data Processing. We sent each new sheriff a fairly intense mail campaign coupled with calls by our local sales rep. The campaign succeeded rather well. From the time of the launch, we grew to $300 million in revenue in about two years.

I didn’t know it at the time, but we were practicing an art that today is called, the “jobs to be done theory of innovation.” (Click here for a good introduction). Developed by Clayton Christensen and his colleagues, the basic idea is that demographic information doesn’t reveal why a person chooses to purchase a new product or service. If we misunderstand the job to be done, our innovations will miss the mark.

Our startup company, for instance, positioned around big machines for big databases. We wanted to offer ever bigger, pricier machines. The new sheriff profile, however, changed our thinking. To get in the door, we needed to make it easy for the new sheriff to buy something on his own authority. So, we introduced an entry-level machine priced just below a typical VP signature limit.

Similarly, think about why men buy pajamas. We might think they simply want to stay warm. But men in America typically don’t buy pajamas until they have a daughter who is three years old. Their motivation is not to stay warm but to preserve their modesty. If we misunderstand that, we’ll produce far too many cozy, warm, flannel pajamas that men will never buy.

In my experience, good marketers and salespeople use the jobs-to-be-done method naturally and intuitively. They’re good observers and naturally ask a basic question: why do people buy these products? They dig into the data but, more importantly, they observe how people behave and ask insightful questions. The management guru, Ted Levitt,was a natural at this. He noted that people don’t buy gasoline for their cars. Rather, they buy the right to continue driving.

The jobs-to-be-done theory suggests that the key to innovation is sociology, not technology. Do you want your company to be more innovative? It’s time to add more marketers and salespeople – and maybe a sociologist and anthropologist – to your development team.

My Buddy, The Bitcoin Broker

My buddy, Yancey, is a Bitcoin broker. He’s been arranging deals part-time for several years now. About a year ago, he went full time. He seems to be doing fine.

It’s ironic that the Bitcoin needs a broker. In my opinion, the best thing about Bitcoin, and the underlying blockchain, is the potential to disintermediate transactions. By eliminating middlemen, blockchain systems may deliver two major benefits:

- Reduce the cost of transactions;

- Make transactions easier and faster to complete.

Conceivably, the blockchain can produce a world of frictionless commerce where we no longer need trusted intermediaries. It’s ironic that Yancey serves as an intermediary for a technology that aims to eliminate intermediaries.

This suggests the blockchain has not yet reached its full potential. My question for Yancey: will it ever? I chatted with Yancey for about an hour last week. Here are some of the highlights.

- Bitcoin was an experiment. Nobody expected it to sweep the world. It’s more like a science fair project than a NASA space shot. The surprise is that it works not that it’s imperfect. Don’t judge the viability of blockchain or of digital currencies based solely on the Bitcoin experience.

- Bitcoin’s base software ensures that the system can never produce more than 21 million Bitcoins. People can “mine” the coins through computationally intensive transactions. The more miners participating, the more challenging the transactions become. The world has now mined approximately 17 million Bitcoins; we’re still several years away from the limit. This architecture delivers two additional benefits:

- It’s so difficult to create coins that no one entity can dominate the entire system. Dispersed responsibility and record keeping are the keys to Bitcoin’s security, veracity, and trust.

- When the limit is reached, no more coins can ever be created. Thus the currency can’t be inflated as fiat currencies can. If demand rises and supply can’t respond, the value of each Bitcoin will also rise. (As values rise, we’ll need to subdivide Bitcoins into ever-smaller units for day-to-day use. Today, a satoshi is the smallest available sliver – it’s one-hundredth of one-millionth of a Bitcoin or .00000001 BTC.)

- While Bitcoin has captured the headlines, the blockchain is potentially a much greater disrupter. We can make virtually any information fraud-proof. As I’ve reported before, Peruvian landowners are storing their titles in blockchain databases to prevent land fraud. Sports memorabilia collectors want to create a chain of evidence that proves that this baseball was the one Mark McGwire hit for number 70 on September 8, 1998. Antique and fine art dealers similarly want a tamper-proof record of provenance. Authors, artists, and scientists want to prove that their important discovery or manuscript or painting existed on or before a given date. Before blockchain, we needed trusted intermediaries to verify these facts. With blockchain, perhaps we don’t.

- It’s still the Wild West in crypto/block land but settlers are bringing barbed wire to set up fences. Banks, in particular, sense that they are ripe for disintermediation. Why should customers wait for days for a check to clear – while the bank reaps the float – when we can make instantaneous transfers without a middleman? Banks would prefer to cannibalize themselves than have someone else do it for them. To do so, they need some guardrails but would rather not invite full-bore government regulation. They need to show that they can police themselves. (J.P. Morgan’s announcement of JPM coin– which debuted while I was chatting with Yancey – is a step in this direction.)

- People worry about the use of cryptocurrencies to support terrorism, but some constraints are already in place. These include:

- KYC – Know Your Customer – helps institutions identify “bad actors” throughout their transaction chain.

- AML – Anti-Money Laundering – a set of procedures and regulations that help to identify and stop money laundering.

- CTF – Counter-Terrorist Financing – helps institutions identify, trace, and recover illegally obtained assets.

Additionally, the structure of the blockchain itself can help prevent fraud. What’s stored in the blockchain can’t be changed. A bad actor could conceivably add to the blockchain but such additions are easy to identify and trace.

- Arbitrage by hedge funds is driving much of the trading in Bitcoin (and other digital currencies) today. Hedge funds can lock in a price (for two or three hours) and find a buyer at the same time. The fund buys at the spot price minus one or two percent and immediately sells at the spot price. I asked Yancey how I could play this game. He asked if I had $40 million to get started. Not yet.

- Stablecoins are the next wave. Bitcoin has no assets behind it – its value is simply a question of supply-and-demand. In other words, it’s just like a fiat currency. Stablecoins are based on some asset – like Venezuelan oil or Zimbabwean gold. Stablecoins aim to reduce the wild price fluctuations seen in so many digital currencies. The downside? Someone or some entity has to manage the physical asset. Once again, we have to place our trust in an intermediary.

- The JPM Coin is an interesting variant of a stablecoin. It’s linked to the dollar: one JPM coin = one dollar. So, the coin is based on an asset. But the asset – the dollar – is not based on anything. It’s a fiat currency. It’s not clear if this will help or hinder the adoption of JPM Coin.

- The next wave of competition will come at the platform level. Several different companies have created platforms for creating blockchain systems. It feels like the database wars of the early 80s. Which one (or ones) will dominate? More on that the next time I catch up with Yancey.

Tongue-tied On Valentine’s Day?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

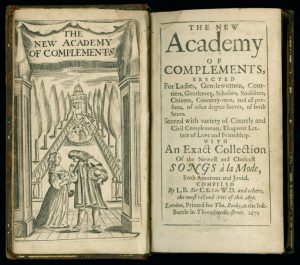

By happy accident, I discovered a partial answer in the Newberry Library in Chicago. The Newberry holds a copy of The New Academy of Complements published in London in the 17th century. The small book – easily tucked in a pocket — is addressed to “both Sexes” and contains a “variety of Courtly and Civil complements” as well as “Eloquent Letters of Love and Friendship … both amorous and jovial.” Happily, the compliments are compiled by “the most refined Wits of the Age.”

What were the best amorous compliments of 17thcentury England? Here are a few of my favorite selections. *

Complemental Expressions towards Men, Leading to The Art of Courtship.

Sir, Your Goodness is as boundless, as my desires to serve you.

Sir, You are so highly generous, that I am altogether senceless.

Sir, You are so noble in all respects that I have learn’d to love, as well as to admire you.

Sir, Your Vertues are so well known, you cannot think I flatter.

Complements towards Ladies, Gentlewomen, Maids, &c.

Madam, When I see you I am in paradice, it is then that my eyes carve me out a feast of Love.

Madam, Your beauty hath so bereav’d me of my fear, that I do account it far more possible to die, than to forget you.

Madam, Since I want merits to equallize your Vertues, I will for ever mourn for my imperfections.

Madam, You are the Queen of Beauties, your vertues give a commanding power to every mortal.

Madam, Had I a hundred hearts I should want room to entertain your love.

I don’t have room to quote many of the gems contained in the book, but here are a few of the categories. Each category provides several models of what to say or write to address the situation. Who knows – you might need one from time to time.

A Gentleman of good Birth, but small Fortune, to a worthy Lady, after she had given a denial.

The Ingratiating Gentleman to his angry Mistriss.

The Lover to his Mistriss, upon his fear of her entertaining a new Servant.

The Jealous Lover to his beloved. The Answer: A Lady to her Jealous Lover.

A crack’t Virgin to her deceitful Friend, who hath forsook her for the love of a Strumpet.

A Lover to his Mistriss, who had lately entertained another Servant to her bosom, and her bed. The Answer: The Lady to her Lover, in defence of her own Innocency.

As you can see, The Academy provides the words to address (and perhaps remedy) most any situation. Is a bald man bothering you? Here’s how to respond:

Sir…while I could be content to keep my Coaches, my Pages, Lackeys, and Maids, I confess I could never endure the society of a bald pate.

I think the Newberry might find an interesting niche market by publishing high quality Valentine’s cards with extracts from The Academy. I know I would buy some. In the meantime, I hope you can find an appropriate quote for whatever your needs are this Valentine’s Day

* The edition held by the Newberry Library was published in 1671. The selections in this article are drawn from the 1669 edition

Will AI Be The End Of Men?

A little over two years ago, I wrote an article called Male Chauvinist Machines. At the time, men outnumbered women in artificial intelligence development roles by about eight to one. A more recent report suggests the ratio is now about three to one.

The problem is not just that men outnumber women. Data mining also presents an issue. If machines mine data from the past (what other data is there?), they may well learn to mimic biases from the past. Amazon, for instance, recently found that its AI recruiting system was biased against women. The system mined data from previous hires and learned that resumés with the word “woman” or “women” were less likely to be selected. Assuming that this was the “correct” decision, the system replicated it.

Might men create artificial intelligence systems that encode and perpetuate male chauvinism? It’s possible. It’s also possible that the emergence of AI will mean the “end of men” in high skill, cognitively demanding jobs.

That’s the upshot of a working paper recently published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) titled, “The ‘End of Men’ and Rise of Women In The High-Skilled Labor Market”.

The paper documents a shift in hiring in the United States since 1980. During that time the probability that a college-educated man would be employed in a

“… cognitive/high wage occupation has fallen. This contrasts starkly with the experience for college-educated women: their probability of working in these occupations rose.”

The shift is not because all the newly created high salary, cognitively demanding jobs are in traditionally female industries. Rather, the shift is “….accounted for by a disproportionate increase in the female share of employment in essentially all good jobs.” There seems to be a pronounced female bias in hiring for cognitive/high wage positions — also known as “good jobs”.

Why would that be? The researchers consider that “…women have a comparative advantage in tasks requiring social and interpersonal skills….” So, if industry is hiring more women into cognitive/high-wage jobs, it may indicate that such jobs are increasingly requiring social skills, not solely technical skills. The researchers specifically state that:

“… our hypothesis is that the importance of social skills has become greater within high-wage/cognitive occupations relative to other occupations and that this … increase[s] the demand for women relative to men in good jobs.”

The authors then present 61 pages on hiring trends, shifting skills, job content requirements, and so on. Let’s just assume for a moment that the authors are correct – that there is indeed a fundamental shift in the good jobs market and an increasing demand for social and interpersonal skills. What does that bode for the future?

We might want to differentiate here between “hard skills” and “soft skills” – the difference, say, between physics and sociology. The job market perceives men to be better at hard skills and women to be better at soft skills. Whether these differences are real or merely perceived is a worthy debate – but the impact on industry hiring patterns is hard to miss.

How will artificial intelligence affect the content of high-wage/cognitive occupations? It’s a fair bet that AI systems will displace hard skills long before they touch soft skills. AI can consume data and detect patterns far more skillfully than humans can. Any process that is algorithmic – including disease diagnosis – is subject to AI displacement. On the other hand, AI is not so good at empathy and emotional support.

If AI is better at hard skills than soft skills, then it will disproportionately displace men in good jobs. Women, by comparison, should find increased demand (proportionately and absolutely) for their skills. This doesn’t prove that the future is female. But the future of good jobs may be.