Do Nudges Work? Should We Use Them?

It’s for your own good.

Ever since Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein published Nudge in 2008, we’ve been debating the ethics and practicality of “nudging” people into making the “right” decisions.

Thaler and Sunstein mine the same intellectual vein worked by Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Dan Ariely, and Charles Duhigg. We may think we make rational decisions but we have biases, habits, and quirks that inject a degree of irrationality into every decision we make. While the other researchers explain how our heuristics work, Thaler and Sunstein give practical advice for nudging people toward rational decisions that serve their best interests.

Thaler and Sunstein refer to their work as “libertarian paternalism”. It sounds like an oxymoron but the basic idea is that you still have the right to screw up your life by making bad decisions. At the same time, we (whoever “we” is) will nudge you into making decisions that are good for you.

Most observers seem to have accepted that nudging by the government or by your employer is ethically acceptable. After all, it’s good for you, right? But there is a minority that objects to the paternalism inherent in the concept. For instance, Michael Beran writes that, “The authors of Nudge seem not to understand that the welfare of a people depends in part on their being free to choose badly. … Probably most people … can point to experiences where their mistakes proved fruitful. … Should we gradually foreclose the freedom to be stupid, we will almost certainly end up being less intelligent.”

So is nudging libertarian paternalism, as Thaler and Sunstein would have it or false benevolence, as Beran would put it? It seems like a debate that’s worth having … but not before we answer a more basic question: does nudging work? Why bother to debate the ethics of a concept if it doesn’t actually work?

So, does nudging work? We have a lot of anecdotal evidence that making one choice easier than another can nudge people in the “right” direction. For instance, if we want to encourage organ donations, we can offer people a choice to donate or not when they get their driver’s license. The driver’s bureau can structure the default option in one of two ways: 1) You’re not a donor unless you opt in; 2) You are a donor unless you opt out. It seems likely that Option 2 would nudge people in the right direction.

As we know, however, anecdotal evidence is very weak. We tend to make up stories that fit our preconceived notions. And Frank Pasquale, writing in The Atlantic, argues that nudges are often too weak to overcome ingrained behaviors. So, is there any controlled, randomized research that would answer a simple question: does nudging work?

Somewhat surprisingly, the first such research was published just last month in Science magazine. (Click here). John Bohannon, the article’s author, reports on 15 controlled trials that involved more than 100,000 people in the United States. The trials involved signing up for various government-supplied social services. In each case, some randomly selected participants were given the “standard application.” Other participants were given a “psychological nudge in which the information was presented slightly differently … for instance, … one choice was made easier than another.”

The results? “In 11 of the trials, the nudge modestly increased a person’s response rate or influenced them to make financially smarter decision.” Bohannon includes data on three of the trials, which moved decisions in the right direction by 2.9%, 3.6%, and 11%. As Bohannon notes, these are modest changes but the costs were probably low as well (no data were given on costs). If so, the cost-benefit may be positive as well.

We now have some solid evidence that nudges actually work. We don’t know the cost-benefit ratios but let’s assume for a moment that they’re positive. If so, the question becomes, should we encourage the government to use them? On the one hand, as Bohannon notes, businesses pay billions of dollars per year for their own nudges, known as advertising. Why shouldn’t the government participate on (closer to) equal footing? On the other hand, libertarians argue that it’s really another kind of nudge – toward the nanny state. I’ll write more about the debate in the future. In the meantime, what do you think?

The Best Way To Disagree

I disagree.

I find that I often disagree with people. It’s not that I’m a bad person or that I have evil intentions. I just have a specific and somewhat idiosyncratic way of looking at the world that doesn’t always fit with other people’s views. There’s certainly nothing wrong with being out of step with the world. There are, however, good reasons to consider how to deal with it.

When I was younger and snarkier, I dealt with it by being competitive. I focused on winning. I’m pretty good with words and I could often come up with a snappy comeback or putdown. I could be sarcastic and snide. I could put the other person in his place. If I left the other person speechless, so much the better. That just proved that I had won the encounter. I felt superior.

Now that I’m a bit older, I realize that it’s more important to win over than to win. When I sarcastically put someone down, I doubt that I won many hearts and minds. Instead of winning people over, I pushed them away. Humiliating another person may feel good but it doesn’t do good.

I’ve learned that the best way to disagree is to begin by agreeing. You start by finding some point of agreement with the other person’s position. It may be small or large, but it allows you to start by validating what the other person has said. You say – metaphorically or literally – “Yes, I’ve heard you. I understand your position.” The other person feels affirmed and recognized.

Then you change the frame, shift the focus, or alter the timeline. Here are some general-purpose ways to do just that:

- Alter the timeline – “I agree that your suggestion would be helpful in the short run. But I worry that the long-term effects would be very detrimental. Here’s why…” (Of course, you can flip long-term and short-term if that suits your argument).

- Agree conceptually then shift to the literal or practical aspects of the issue – “I think you’re right. A successful businessman should make a good president. I would just feel better if we had an example of that actually happening.”

- Agree with your interlocutor’s frame of reference and then change the frame. Often, you’ll want to broaden the frame, like this: “I certainly agree that this would help first graders. But I’m concerned about all primary school students. How can we determine if this will help all students, not just beginners?” On other occasions, you may want to narrow the frame, like this: “I agree that this tax change will be good for most companies in our industry. But our company is an exception because of the way we account for our overseas profits.”

The general technique is known as concession-and-shift. It’s been in use at least since the days of Aristotle and his rhetorical colleagues. The idea is simple: start on a positive note rather than a negative note. Agree before disagreeing. If your interlocutor senses that you’re agreeable and reasonable, she’ll be much more likely to listen to your side of the argument. That’s exactly what you want.

When I Met Muhammad Ali

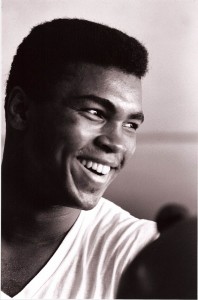

The smile.

In 1968 or 69, when I worked on the student newspaper at the University of Delaware (UD), I drew an assignment to interview Muhammad Ali. I was a fairly random choice since I didn’t cover sports. But the angle of the story was Viet Nam and the antiwar movement. Since I wrote about politics, I volunteered eagerly to meet the man behind the legend.

At the time, Ali was in his three-and-a-half year exile from boxing. In 1967, Ali had refused to be drafted in the army and filed for conscientious objector status. He also made the memorable statement, “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong. No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.” His political positions coupled with his fame made him one of the most polarizing figures of American history. Boxing commissions stripped him of his title and no state would grant him a license to fight. (The Supreme Court later unanimously granted him conscientious objector status and he resumed his boxing career).

My assignment was straightforward. Ali was on a speaking tour of college campuses and was preparing to give a speech at Delaware State University. I was to drive to DSU and, with a dozen or so other journalists, spend an hour interviewing him. The fact that Ali was speaking at DSU, instead of UD, was telling. Though the state of Delaware was a not “southern”, its educational system was highly segregated. The University of Delaware was for white students; Delaware State was for black students. Indeed, Delaware State was founded in 1891 as the State College for Colored Students. Perhaps for obvious reasons, Ali chose to speak at Delaware State.

Ali was a member of the Nation of Islam, often referred to as Black Muslims. (He later converted to mainstream Islam). At the time, the Nation of Islam advocated the separation of races and viewed “white devils” as an inferior race created by an evil scientist. On judgment day, white people would be destroyed.

I had followed Ali’s career closely and knew something about his strength and speed. It’s a little known fact that I boxed in the Golden Glove preliminaries in high school. I wanted to box like Ali. I knew that we were both the same height – 6 foot 3. His reach was 78 inches. So was mine. He was fast. So was I. The difference: he weighed 215 pounds and was athletic. I weighed 160 pounds and was nerdy. I could float like a butterfly but my sting was like a damp Kleenex.

I found my way to the right building on the Delaware Sate campus. The meeting room was just down the hall and around the corner. I rounded the corner and practically tripped over Muhammad Ali.

I wasn’t prepared and didn’t know what to expect. I was eager to meet him but also nervous. He was the most famous person I ever met (still true today). But perhaps he wouldn’t be happy to see me. Perhaps he would deem me a white devil and ban me from his presence. But, in fact, he was one of the most gracious people I have ever met. I was stammering awkwardly and he had no particular reason to be nice to me but he welcomed me warmly and offered me a hand that seemed twice as large as mine.

Since we were the same height, I assumed that I could look him in the eye. But no – he seemed so much bigger than I was. I don’t know where charisma comes from but he had it in vast quantities. He was far more charismatic than Bill Clinton, whom I met many years later. Ali seemed to float in the air in front of me.

I’ve just read several obituaries of Muhammad Ali. They discuss his athletic prowess, his political views, his religious development, and, course, his verbal jousting. What I saw was a thoughtful, caring, magnetic individual who invited me into his world for about an hour.

During the press round table, I know I asked some questions, but I don’t remember them. I know I wrote an article, but I don’t remember it. What the obituaries don’t mention was his smile. It was magnanimous and all encompassing. That’s what I’ll remember.

Filtering Water In The Information Desert

It’s a desert out there.

In organizations, large transformation efforts create information deserts. Traditional sources of information dry up. We search for new sources but they’re few and far between. When we do find them, we can’t be sure if the information is tainted or pure. Should we consume it or not?

The lack of information creates additional stress. We know we’re going on a “journey” but we don’t know where. We don’t even know how we’ll know when we get there. Perhaps we’ll never get there. Perhaps we’ll just continue transforming.

We also know that there will be some winners and losers in the process. Some people will get plum assignments; others will be relegated to minor roles. It’s not always clear who will make these decisions or how they will be made. So we don’t know how to behave to improve our chances of success.

We also fear that we’ll lose something. We know what we have today. While it may not be all we want, just knowing what we have brings some degree of comfort. As the organization morphs, we don’t know what we’ll have tomorrow. We could be worse off. Our loss aversion bias makes the possibility of loss seem more likely – and more painful – than the possibility of gain.

When we’re in a real desert, we want to find water. Indeed, we want to find good water. Drinking bad water could be worse than drinking no water at all. So we carry water filtration systems. When we find water, we can purify it and ensure that it will help us rather than harm us.

Similarly, in an information desert, we want to find good, trustworthy sources of information. Since traditional sources of information have dried up, we need to find new sources. But how can we tell if the new sources are trustworthy? Perhaps they’re tainted with rumor and conjecture. Perhaps consuming the information will do us more harm than good.

It’s not easy to create accurate and effective information for a transforming organization. But there are some good filters that can help employees distinguish good information from bad. The simplest one I’ve found is called the triple filter. Some writers say that Socrates created the filters. Others claim Arab philosophers developed them. Regardless of the source, it’s a good communication technique to keep in mind.

According to legend, when someone offered Socrates information – especially information that might be based on conjecture or rumor, he asked three sets of questions:

- Is it true? How do we know? How can we verify it? What’s the source? What’s the evidence?

- Is it good? This is especially important if the information is about a person. Does it portray the person in a good light? Is it kind? Does it assume positive intent?

- Is it useful? Is the information useful to me, the recipient? Can I use it to accomplish something positive?

The process is analogous to deciding what evidence is admissible in court. If the information didn’t pass all three tests, Socrates simply refused to hear it.

I think of these questions as three steps in a linked process. If the information can’t pass the first test – truth — there’s not much point in asking the other two questions. If the information is verifiably true, then it’s useful to continue the process. If the information passes all three tests, then it’s admissible and should be considered in decision making.

Organizations in transition are under a great deal of stress. Bad information only increases the pressure. The triple filter doesn’t make the desert bloom but it helps employees find oases of trust and certitude in a difficult and demanding environment.

Consciousness Is A Verb

It’s not in here.

We live in an individualistic culture and I wonder if that doesn’t bias our understanding of how we behave and think. For instance, we view humans as self-contained and self-sufficient units. There’s a clear boundary between one human and another. Similarly, there’s a clear boundary between each individual and the environment around us. We are separate from each other and from the world.

But what if that’s not the case? What if humans are entangled with each other in much the same way that quantum particles are entangled? Mirror neurons are still somewhat mysterious but what if they allow us to entangle our thoughts with those of other people? Similarly, we’ve learned in the recent past that we think with our bodies as much as our brains. What if our thinking actually extends beyond our bodies and interacts with other thoughts?

Similarly, what if the environment is not separate from us but part of us? What if the environment shapes us much like a river shapes a stone? In a sense, it would mean that we’re not entities but processes. We’re not things but actions. The Buddhists might be right: impermanence is the very essence of our being.

If these things are true, it may give us a key to understanding consciousness. Defining consciousness is known as the “hard problem”. Neuroscientists often phrase the question simply: “What is consciousness?” What if that’s the wrong question? The question implies that consciousness is a thing. It also suggests that consciousness exists somewhere, most likely in the brain. But what if consciousness is not a thing but an action? What if it’s something we do as we interact with the environment? What if we’re swimming in consciousness?

You may have guessed by now that I’ve been reading the works of the philosopher, Alva Noë. (See here and here). Noë studies perception and consciousness and tries to understand how they are entangled. Noë states flatly that, “Consciousness is not something that happens in us. It is something we do.”

Noë goes on to compare consciousness to a dancer, who is influenced by myriad external factors, including the music, the dance floor, and her partner. Dancing is not within the dancer. Noë writes that, “The idea that the dance is a state of us, inside of us, or something that happens in us is crazy. Our ability to dance depends on all kinds of things going on inside of us, but that we are dancing is fundamentally an attunement to the world around us.” Similarly, Noë suggests, consciousness is not within us, rather it is “…a way of being part of a larger process.”

Noë similarly argues that consciousness is not located in a given place. The analogy is life itself. If we look at other people, we can tell that they’re alive. But where is life located in them? We quickly realize that we don’t think of life as a thing that is located in a certain place. Life is not a thing but a dynamic. Noë argues that the same is true of consciousness.

Noë also suggests that cognitive scientists are pursuing the wrong analogy – the computer. This “distinctively nonbiological approach” converts consciousness into a mere computational function that is “…very much divorced from the active life of the animal.” The active life – and engagement with the world around us – creates consciousness in a way that a “brain in a vat” could never do.

What’s it all mean? We’re looking for consciousness in all the wrong places. As Noë concludes, “…the idea that you are your brain or that the brain alone is sufficient for consciousness is really just a mantra, and … there is no reason to believe it.”