Innovation and Memory

Do you forget stuff? Yeah, me too. It makes it harder to be innovative.

The trouble is that innovative ideas don’t come all polished up and wrapped in a pretty bundle. When a creative person describes her process, it may seem that innovative new ideas arrive in a flash of insight. That’s a nice way to tell a story but it’s not really the way it happens.

In truth, innovation is more like building a puzzle — when you don’t know what the finished piece is supposed to look like. You collect a piece here and a piece there. Perhaps, by putting them together, you create another piece. Then, a random interaction with a colleague supplies another piece — which is why random interactions are so important.

Each piece of the puzzle is a “slow hunch” in Steven Johnson’s phrase. You create a piece of an idea and it hangs around for a while. Some time later — perhaps many years later — you find another idea that just happens to complete the original idea. It works great if, and only if, you remember the original idea.

In previous posts on mashup thinking, I may have implied that you simply take two ideas that occur more or simultaneously and stick them together. But look a little closer. One of my favorite mashup examples is DJ Danger Mouse, who took the Beatle’s White Album and mashed it up with Jay Z’s Black Album to create the Grey Album, one of the big hits of 2004. But how long was it between the White Album and the Black Album? Well, at least a generation. I remember the White Album but not the Black Album. I think our son is probably the reverse. Neither one of us could complete the idea. DJ Danger Mouse’s originality comes from his memory. He remembered a “slow hunch” — the White Album — and mashed it into something contemporary.

So, how do you remember slow hunches? By writing them down. In fact, that’s one of the reasons I started this blog — so I won’t forget good ideas. I can now go back and search for ideas that I thought were important several years ago. I can recall them, put them together with new hunches, and perhaps create new ideas.

I like to read widely. I’m hoping that ideas — both old and new — will collide more or less randomly to create new ideas. Unfortunately, I often forget what I read. With this blog, I now have a place store slow hunches. And, since it’s public, I’m hoping that you’ll help me complete the cycle. Let’s get your random ideas colliding with my random ideas. That will help us both remember, put our hunches together, and come up with bright new ideas. Sounds like a plan. Now we just need to remember to stick with it.

Innovation: Making the Connection

Anybody want to connect?

Making connections is the basis of creativity and innovation. It’s very rare that somebody comes up with a full-blown idea on their own. Instead, they master a domain and then extend it. They learn a paradigm and then change it. They make the connection between this idea and that one. They put two and two together.

So, how do you actually make connections? I think of it as a three-level problem. First, we make new connections within our own brains. Second, we connect with other people who are more or less like us. Third, we need to expand our horizons and connect with people who aren’t like us. Here are some practical tips for each level.

In our own brains — as numerous authors have pointed out, the brain is plastic. It can change itself and enrich itself even after it stops growing. Can we teach our brains to make new connections? You betcha:

- Read things (or watch things) that you disagree with. If you only read authors who agree with your political or philosophical bent, you’re only reinforcing existing connections. Reading authors you disagree with will help you establish new connections.

- Use you non-dominant hand more often — connect to your “other” side.

- Study a foreign language — we think with words. Learn some new words and you’ll learn to think differently.

- Play games that exercise your brain — try bridge or crossword puzzles or sudoku. They all require you to see things differently and remember things accurately.

Other people like us — let’s take the context of a company’s headquarters building. How do you build connections between employees? We’re all familiar with team-building exercises. Let’s look at a few less obvious ways to connect:

- Reduce the number of coffee stations — get people to congregate at central locations. As they bump into each other, they’ll talk to each other, too.

- Reduce the number of bathrooms — same idea, get people to congregate in central locations.

- Design physical spaces that get people to carom off each other — look at the old Bell Labs architecture. Long, narrow hallways with offices arrayed along them. Step out of your office and you’re on a highway full of people. It’s hard not to bump into somebody.

- Book clubs — sponsor a book of the month club for all employees. Hint: don’t just do business books. Range farther afield into history, sociology, fiction, and so on.

Other people not like us — who is not like us? Well, if I’m in the accounting department, then sales people are not like me. Making connections with sales people might just lead to great new ideas. I see a lot of team building within departments (a team retreat for the marketing department, for instance) but not so much between departments. Here are a few ideas:

- Random seating — why is it important for accountants to sit with accountants and engineers to sit with engineers? Randomize things so that people sit by people who are different.

- Onboarding programs — help new employees make contacts across the company; not just in their own department. Early connections last a long time.

- Team building with other departments — emphasize collaboration rather than competitions. Form coss-departmental teams or go on retreats together. Get people to know each other.

- Travel more — face-to-face meetings are the best way to get to know people, especially people who are different from you.

- Connect with customers — develop programs that require your employees to work with your customers. Make the effort to bridge the gap.

Innovation and the City

I’m looking for a connection.

Let’s say that the city of Groverton has 100,000 residents and produces X number of innovations per year. Down the road, the city of Pecaville has 1,000,000 residents. Since Pecaville has ten times more residents than Groverton, it should produce 10X innovations per year, correct?

Actually, no. Other things being equal, Pecaville should produce far more than 10X innovations. In predicting innovation capacity, it’s not the number of people (or nodes) that counts, it’s the number of connections. The million residents of Pecaville have more than ten times the connection opportunities of the residents of sleepy little Groverton. Therefore, they should produce much more than ten times the number of innovations.

In Where Good Ideas Come From, Steven Johnson makes the point that connections are the fundamental unit of innovation. The more connections you can make, the more likely you are to create good ideas. Scale doesn’t matter — more connections are better at a very small scale or a very large scale. This is where cities come in. In terms of innovation, larger cities have multiple advantage over smaller cities, including:

- There are more “spare parts” lying around — Johnson points out that most new ideas are created by combining — or connecting — existing ideas. Existing ideas are “spare parts” that an enterprising “mechanic” can assemble in new ways. (In an earlier post, I referred to this as mashup thinking. Click here.) Cities have more of everything, including more spare parts to fool around with.

- More information spillover — I know a lot about information science. If I keep it to myself, it doesn’t do a lot of good. If I share it with, say some sociologists, we might just come up with something useful. My information spills over to them and vice versa. In Johnson’s terms, the information I share becomes spare parts that the sociologists can plug into their framework. The question is: how likely am I to meet up with a bunch of sociologists? It’s much more likely in a big city than a small town.

- Not only are there more connections, the connections are more varied — if I mainly talk to people who are like me, the chances of something innovative happening are fairly low. It’s when I talk across boundaries — to people who aren’t like me — that interesting ideas begin to emerge. It may happen when I bump into a random sect of sociologists. But if it doesn’t happen then, well… maybe it will happen when I encounter an enclave of entomologists. Or maybe I’ll bump into a bevy of brewers who need to know about information science. In a big city, I’m likely to interact with many more disciplines, opinions, experts, and enthusiasts than I am in a small town.

Does this work in real life? Johnson provides some very interesting anecdotes. More recently, last Friday’s New York Times had an article (click here) on manufacturing and innovation. The article argues that more innovation happens when designers are close to the manufacturing floor. Why? Because of information spillover. Researchers claim that offshore manufacturing reduces our ability to innovate precisely because it reduces information spillover. Connectivity seems to work on the manufacturing floor as much as it does in big cities. Scale doesn’t matter. Bottom line: if you want to be more innovative, get connected.

Innovation and Diversity

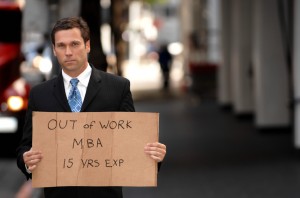

Do you have an MBA? So do most of the people I work with at my client organizations. One of the ways I add value is merely by the fact that I don’t have an MBA.

It’s not that having an MBA is a bad thing. It’s that so many companies are run by people educated in the same way — they all have MBAs. The fact that I don’t have an MBA doesn’t mean that I think better than they do. But I do think differently. Sometimes that creates problems. Oftentimes, it creates opportunity.

If all your employees think alike, then you limit your opportunity to be creative. Creativity comes from connections. By connecting concepts or ideas in different ways, you can create something entirely new. This works at an individual level as well as an organizational level. If you read only things that you agree with, you merely reinforce existing connections. If you read things that you disagree with, you’ll create new connections. That’s good for your mental health. It’s also good for your creativity.

At the organizational level, connecting new concepts can lead to important innovations. Indeed, the ability to innovate is the strongest argument I know for diversity in the workforce. If you bring together people with different backgrounds and help them form teams, interesting things start to happen.

In this sense, “diversity” includes ethnic, economic, and cultural diversity. It especially includes academic diversity. As a leader, you want your engineers, say, to mix and mingle with your humanities graduates. Perhaps your lit majors could improve your MBAs’ communication skills. Perhaps your philosophers can help you see things in an entirely new light. In today’s world, innovation requires that you bring together insights from multiple disciplines to “mash up” ideas and create new ways of seeing and doing.

Most companies keep data on ethnic diversity within their workforce. However, they don’t usually keep statistics on the different academic specialties represented among their employees. You may well have enough MBAs. But do you have enough linguists? Philosophers? Sociologists? Anthropologists? Artists? If not, it’s time to start recruiting. The result could well be a healthier, more innovative company.

Mash, Mash, Innovation

What do DJ Danger Mouse and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) have in common? They’re examples of one of the main engines of innovation: the mashup. Some innovations involve the creation of something entirely new. More often, innovations combine existing concepts from different domains. The concepts are well understood. The innovation comes from mashing them up — combining concepts to create something new.

What do you get if you combine wheels with luggage? Rollable luggage. (Why did it take us so long to figure that out?) What do you get if you add a power supply? Self-propelled luggage. That sounds like a good business idea.

We even have jokes that follow the same pattern. What do you get when you cross a snowman with a vampire? Frostbite. (I didn’t say they were good jokes).

Mashup thinking can lead to stunning new product development, devices, tools, and processes. What do you get when you cross an X-ray with data processing? The MRI. Mashup thinking is also fairly easy to master. You just add things together. Sometimes the result doesn’t make sense but often times, it leads you to an intriguing discovery. If you want to be more innovative, think about doing the mash.

So, what do DJ Danger Mouse and IEDs have in common? Well, watch the video.