Which Companies Are The Most Innovative?

Change Is Coming

Last week, I wrote about which countries are the most innovative. (Hint: Switzerland and Sweden topped the list). This week, let’s discuss which companies are the most innovative.

Boston Consulting Group (BCG) just published their eighth annual compilation of the most innovative companies in the world. BCG collected data from 1,500 executives and rated and ranked the 50 companies that are deemed the most innovative.

Innovation continues to be a very high profile objective. Over three-fourths (77%) of the respondents noted that innovation was among the top three strategic imperatives for their respective companies. This is a steady upward trend since a low point of 64% in 2009, when companies presumably had other things on their mind. This trend seems to match a similar “return to innovation” trend at the national level.

So which companies are the most innovative? Apple continues to claim the top spot but Samsung has leapfrogged over Google to stake a strong number two position. Samsung has built an innovation culture around the slogan, “Change everything but your spouse and your children.” As BCG reports, building a culture that emphasizes and accepts change is one of the keys to success.

High tech companies take six of the top ten positions. In addition to Apple, Samsung, and Google in the top three slots, Microsoft is fourth, IBM is sixth, and Amazon is seventh.

The presence of top tech companies is not a big surprise. The bigger surprise for me was that three car companies vaulted into the top 10: Toyota is fifth, Ford is eighth, and BMW is ninth. Perhaps even more impressive is that car companies accounted for nine of the top 20 slots. GM is 13th, VW is 14th, and Hyundai, Honda, Audi, and Daimler take positions 17 through 20.

BCG suggests that three major factors are pushing the car companies towards greater innovation. First, “…manufacturers are racing to meet higher fuel-efficiency standards”. Second, many companies are investigating and experimenting with electric vehicles. Third, “…safety standards continue to rise”.

What causes companies to be innovative? Based on this year’s crop of leaders, BCG notes that there are five critical factors. I’ll write more about these in the future but here’s a first take:

- Top management is committed to – and fosters a culture of – innovation as a competitive advantage. Like Samsung, the leaders of the leading companies push hard for innovation.

- They leverage their intellectual property. They understand the rules of the IP game and they manage – sometimes buying, sometimes selling – complex portfolios of patents and other intellectual property.

- They manage a portfolio of innovative projects. They generally guide multiple projects simultaneously. Some are world changers; others are incremental enhancements. Management understands the project process and has a good sense of when to fish and when to cut bait.

- They have a strong customer focus. They continually ask the question, “What’s good for the customer?”

- They develop “strong processes, which lead to strong performance”. They often have standardized processes that require inter-disciplinary leaders to make conscious decisions about where to invest (and where not to).

Which Country Is The Most Innovative?

Earlier this year, I wrote about the Global Innovation Index for 2012 (and its relationship to happiness research). The 2013 GII report was recently published and surveys 142 different economies. Here’s how the Top 10 countries shifted from 2012 to 2013.

|

GII 2012 |

GII 2013 |

|

Switzerland |

Switzerland |

|

Sweden |

Sweden |

|

Singapore |

UK |

|

UK |

Netherlands |

|

Netherlands |

USA |

|

Denmark |

Finland |

|

Hong Kong |

Hong Kong |

|

Ireland |

Singapore |

|

USA |

Denmark |

|

Luxembourg |

Ireland |

The first thing you’ll notice is that the same countries dominate the leader board. Luxembourg has dropped out of the Top 10 and Finland has moved in but, otherwise, the countries are the same. The second major item is that the Nordic countries — Sweden, Finland, and Denmark — rate quite well. (Additionally, Iceland is 13th and Norway is 16th — all the Nordic countries are in the Top 20). These countries also dominate the leadership slots in research on national happiness. Apparently, there’s a connection between happiness and innovation.

You’ll also notice that Switzerland and Sweden take the first two positions in both years. The GII uses 84 indicators to rank countries on their ability to innovate. Switzerland and Sweden score high across the board. In terms of innovation, both countries deliver very balanced performance.

With the theme, “The Local Dynamics of Innovation” this year’s report looks not only at national level metrics but also at very specific, local phenomena. Here are some findings:

- Innovation hubs – these are physical locations such as Silicon Valley, Baden-Württemburg in Germany, or the Mumbai region in India. Typically, large enterprises serve as “hub champions” but government programs and policies can also play a major role. The hubs provide ideas, capital, and connections and create a virtuous circle — success breeds success.

- Democratization of innovation – companies and governments all over the world are investing in innovation and innovation hubs. The Internet has democratized innovation as has the rise of English as the global language of business. The report suggests that the region that has made the greatest strides in innovation is Latin America, with Costa Rica leading the way.

- Open innovation is growing – this is the opposite of the not-invented-here syndrome. Ideas are open and shared. Companies grant their ideas to third parties and use ideas from multiple sources. Sources may include companies, universities, or government research programs.

- Innovation is recovering – after a sharp drop in 2009, companies and governments have resumed investing in innovation. For instance, worldwide patent applications grew 7.5% in 2010 and 7.8% in 2011, significantly higher than before the crisis.

I’ve always thought that innovations result from collisions. As people, ideas, and cultures collide, creative combinations emerge in the form of innovations. The Global Innovation Index seems to confirm this on a global scale. Democratization, openness, and the hub concept suggest that “collisions” are happening more frequently and more pervasively. If so, we should see an acceleration of innovation over the next decade.

Innovation – The Wide View

Showroom Online

Suellen used to work for a company founded on a great idea – there’s a lot of information out there and, if you can organize it, you can sell the organized information for a lot more than the raw data. The company, Information Handling Services (IHS), got its start by organizing and re-selling government information and military and technical specifications. (Today, the company offers a whole range of analytic and forecasting services as well).

Though IHS is very successful, I’d like to use one of their less successful products to illustrate an insight about innovation. In the early 90s, IHS identified an underserved market: home furnishing suppliers and designers. The information about home furnishings – furniture, carpets, upholstery, cabinets, fixtures, etc. – was highly fragmented. Designers who wanted to buy furnishings had an extremely difficult time identifying, locating, and evaluating their choices.

It seemed a perfect market for IHS. After all, they were experts at gathering and organizing information and making it easily searchable. And that’s just what they did. They contacted furnishings suppliers, gleaned the necessary information, and put it into an electronic system – called Showroom Online — that designers could search in a variety of ways. (For instance, “Find all Louis XIV style chairs that cost less than $1,000 and are available within six weeks”).

Then the IHS designers made a fateful technology decision. They chose to store and distribute the data on 12-inch LaserDiscs. LaserDiscs were among the first optical/laser, random-access storage and retrieval media. They were way ahead of their time. And that was the problem. Not many people had LaserDiscs, or understood them, or could afford them.

From what I remember, Showroom Online was a well-designed system. It just had one flaw. It didn’t fit.

I thought of Showroom Online as I was reading The Wide Lens, Ron Adner’s new book on innovation. Adner argues that, all too often, innovations fail because we take a narrow perspective. We focus on what we need to do. Adner calls this execution focus: “What does it take to deliver the right innovation on time, to spec, to beat the competition?”

Adner argues that execution focus is what causes failures like Showroom Online. We need to take a wider perspective. Specifically we need to recognize two types of risk:

Co-innovation risk – “…the extent to which the success of your innovation depends on the successful commercialization of other innovations.” (This seems to be what took down Showroom Online).

Adoption chain risk – “ the extent to which partners will need to adopt your innovation before end consumers have a chance to assess the full value proposition.”

This all relates to the issue of framing (which I’ve written about before). If you define your frame narrowly, you’ll miss a lot of important information. Other people – politicians, salespeople, teachers – may try to define the frame for you but you can also frame yourself. The trick is to take a step back, look around, and broaden your horizons. That’s important to you personally. It’s even more important to your innovation.

Creativity Templates – 2

Pictorial Analogy

A few days ago, I wrote about the study that Jacob Goldenberg et. al. used to demonstrate the effectiveness of creativity templates. Goldenberg and his associates used several different methods to create and test ads. They found that six creativity templates – though not foolproof – consistently created better ads than alternative methods.

So what were the templates? Here they are. (Note: Some of the examples used come from the original article, others come from my experiences).

Template 1 – Pictorial Analogy – uses a picture to exemplify the product (or product attribute) in a compelling way. Two basic versions exist:

Version 1 – Replacement – in illustrating the complexity of warehouse management, we used a picture of a gumball machine filled with different colored gumballs. The picture “replaces” the warehouse and emphasizes the difficulty of getting the right inventory off the shelf and delivered to customers.

Version 2 – Extreme analogy – the picture represents something extreme about the product. For instance, running shoes that cushion the shock might be illustrated with landing gear on a space ship touching down on Mars.

Template 2 – Extreme Situation – creates an unrealistic situation to emphasize key attributes.

Version 1 – Absurd alternative – a security alarm ad shows a woman barking at intruders to scare them away. You don’t have to use our alarm system. You can always learn to bark like a dog – an absurd alternative.

Version 2 – Extreme attribute – exaggerate a product attribute to the absurd. To communicate that a Jeep can go anywhere, show it driving along the bottom of the ocean

Version 3 – Extreme worth – exaggerate the worth of a product feature to the absurd.

Template 3 – Consequences – illustrates the (exaggerated or extreme) consequences of using or not using the product.

Version 1 – Extreme consequences – at a B2B software company, we sent hammocks to a select group of CIOs to give them a place to relax after they bought our software.

Version 2 – Inverted consequences – we also sent straitjackets (real ones – very creepy) to another group of CIOs to show them how they would feel if they didn’t buy our software. Note: the straitjackets worked better.

Template 4 – Competition – the product (or attribute) is shown competing with a product from a completely different class

Version 1 – Attribute in competition – to illustrate the speed of a car, show it racing a bullet.

Version 2 – Worth in competition – not how it performs (speed) but how much it’s worth to you

Version 3 – Uncommon use – a young couple’s car breaks down. A friend offers to tow them but doesn’t have a towrope. They use the husband’s jeans as a towrope. An uncommon use that illustrates the product’s toughness.

Template 5 – Interactive Experiment – invites the viewer into an experiment which demonstrates the need for the product or service

Version 1 – Activation version – you actually engage in the experiment. For instance, you’re invited to scratch your head over a black patch in a magazine. If white flakes appear on the black patch, you need our dandruff shampoo

Version 2 – Imaginary experiment – well, imagine this …

Template 6 – Dimensionality Alteration — change the relationship between the product attribute and the environment.

Version 1 – New parameter – change an attribute in the environment to accentuate the product attribute. To accentuate the color of a shirt, create a photo in which everything is in black-and-white except the shirt.

Version 2 – Multiplication – multiply the product (or product attribute) and then compare it to something in the environment. Example: early Hyundai ads, where two Hyundais cost less than one entry-level Toyota.

Version 3 – Division – divide the product into component parts and compare them to each other and/or to the environment.

Version 4 – Time leap – present an ordinary scenario but make it interesting by shifting it to the past or future. A wife argues with her husband about why he cancelled the life insurance. Sounds ordinary, until you realize that it’s set in the future, when the husband is already dead.

Do these templates always work? Well…. no. But I can attest that they are more efficient and effective than classic brainstorming techniques where no answer is wrong and we throw everything on the white board to see what sticks. Go ahead, give ’em a try.

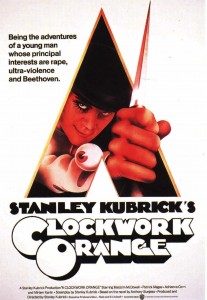

Super Sad Clockwork Orange

What would happen if we mashed up Super Sad True Love Story and A Clockwork Orange?

What would happen if we mashed up Super Sad True Love Story and A Clockwork Orange?

Published in 1962, A Clockwork Orange was set in the not-so-distant future when a gang composed of Alex and his droogs (friends) could wreak ultra-violence all about them. Super Sad True Love Story, published in 2010, was set in a “near-future dystopian New York … dominated by media and retail.” Could they be the same story?

I read A Clockwork Orange in college and re-read it last year when the 50th anniversary edition came out (with the missing last chapter). The author, Anthony Burgess, worried that a novel about the future would age badly if he used contemporary language. Just imagine reading about mods and rockers flipping you the bird while shouting, Climb it, Tarzan. It’s so 60’s

So Burgess famously invented a language – called Nadsat – that included roughly 600 words derived from Russian. Droogs are friends, a britva is a blade or razor, chepooka is nonsense, devotchka is a girl, polezny is useful, rot is a mouth, zheena is a wife, and horrorshow is cool, great, or super. It takes a little while to get used to Nadsat but, once you do, it flows easily.

I re-read A Clockwork Orange because I wanted to see how it had held up. Did Burgess’s trick work? Did Nadsat still sound futuristic? I have to say that it did; it still seemed to be a future language in an undefined but somewhat familiar landscape.

While the language held up, everything else seemed so 60’s. At one point, Alex and his droogs invade a house where an author has nearly finished typing a novel (called A Clockwork Orange). The gang seizes the typescript and shreds it in front of the author. It’s the only copy. The work is forever lost. But wait … a typewriter in the not-so-distant future? How lame is that? The language worked but the technology forecast didn’t.

Gary Shteyngart, the author of Super Sad True Love Story, may have the opposite problem, which is why a mash-up might work. I got to thinking of this when I read Shteyngart’s article, “O.K., Glass” in a recent issue of The New Yorker. The article recounts Shteyngart’s adventures as he wanders around New York wearing Google Glasses. (Shteyngart is one of the Google Glass Explorers, who are sometimes known as Glassholes).

Shteyngart uses his Glass experience to ruminate on Super Sad True Love Story. He notes, for instance that he set the novel in the near future because “…setting [it] in the present in a time of unprecedented technological and social dislocation seemed … shortsighted.”

Shteyngart is addressing the same problem as Burgess: how do you keep a novel fresh? Burgess approached it through language, Shteyngart through technology.

As Shteyngart admits, he didn’t solve the problem of predicting the far future. A lot of what he wrote has already come to pass. He writes that he feels like a “…very limited Nostradamus, the Nostradamus of two weeks from now.”

Still, I submit that Shteyngart did a better job on future technology than Burgess, while Burgess did a better job on future language. That’s why I’m proposing a mashup. Burgess died in 1993 so any mashup will have to come from Shteyngart. Plus, Shteyngart was born in Russia so Nadsat should be a snap for him. So what do you say, Gary? Would you give us a mashup of two great novels? It would be totally horrorshow.