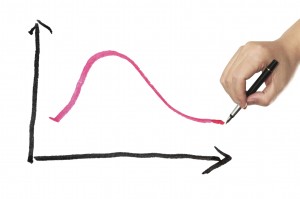

Stress And The Nerve Curve

Nerve Curve.

When I coach an executive on public speaking, I always spend some time reviewing the nerve curve. This is a theoretical curve that plots degree of nervousness on one axis and presentation quality on the other.

The arc of the curve is the same as the arc of a baseball thrown across the diamond. It rises, reaches a peak, and then descends. The lesson is simple: you need to be somewhat nervous to give a good presentation. Nervousness alerts your senses, focuses your mind, and stiffens your spine – all good things for giving a great presentation.

If you follow the nerve curve, you’ll also realize that too much nervousness is a bad thing. The peak of the curve represents your best possible performance. If you become so nervous that you pass the peak, your performance starts to degrade. You might shake, sweat, and stammer. Your audience will be sympathetic; many of them have been there and done that. But they won’t be listening to your message.

Another way to read the nerve curve is that some stress is good for you. A little stress will improve your performance. Too much stress will degrade it. But it’s also true that too little stress will degrade your performance. If we want to maximize performance, being under-stressed may be just as bad as being overstressed.

That’s an interesting perspective for me because my docs have always told me to reduce my stress. They seemed to be saying that all stress – even a small amount – is bad for me. I should strive to eliminate stress. But striving creates stress, doesn’t it?

From my recent readings, I’m beginning to conclude that stress follows the nerve curve. Too little is bad for you; too much is bad for you. You need to attain just the right amount.

So, how do you attain the right amount? Well, not by disengaging from the world. If you try to minimize your stress, you may just get bored. And, as Colleen Merrifield and James Danckert point out in Experimental Brain Research, boredom is stressful. In fact, it may well be more stressful than being sad. (The authors also point out that, “Research on … boredom is underdeveloped.” Sounds like a promising field.)

Your attitude towards stress also seems to play an important role. If you believe that stress is bad for you, and you feel stressed out, you may well conclude that you might drop dead at any moment. That, in itself, is stressful. On the other hand, if you understand the nerve curve, you know that some stress is actually good for you. As you start feeling stressed, you’ll realize that your performance is also improving. You’re more likely to feel energized and engaged rather than stressed and depressed.

So, what’s the lesson here? Try a little stress. It may well be good for you.

My Good Judgment

Who’s the better forecaster?

We’re all familiar with the idea of placing a bet on a football match. You can bet on many different outcomes: which team will win; by how much; how many total goals will be scored on so on. With a large number of bettors, the aggregate prediction is often remarkably accurate. It’s what James Surowiecki calls The Wisdom of Crowds.

Prediction markets aim to do the same thing but broaden the scope. Instead of betting on sports, they bet on political or economic or natural events. For instance, What’s the probability that: Greece will exit the Euro in 2015; or that nuclear weapons will be used in the India/Pakistan conflict before 2018; or that Miami will have more than 100 flood days by 2020?

The forecasting questions are quite precise and always bounded by a time limit. There should be no question whether the event happens or not. In other words, we can actually judge how accurate the forecasts are.

Why is judging so important? As Philip Tetlock pointed out in Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?, we traditionally don’t measure the accuracy of expert political predictions. Pundits make predictions and nobody checks them. Indeed, Tetlock argues that most pundits make predictions as a way to advertise their consulting businesses. The bolder the prediction, the more powerful the ad.

When Tetlock actually measured the accuracy of expert political predictions, he discovered they were essentially useless. Tetlock writes, “The results were startling. The average expert did only slightly better than random guessing.” Remember that the next time you read an expert prediction.

You may remember that I wrote about a prediction market – InTrade – during the 2012 elections in the United States. Based in Ireland, InTrade allowed people all over the world to place bets on who would win the presidential election, as well as various Senate, gubernatorial, and congressional elections. InTrade’s electoral predictions were remarkably accurate. (It did less well in predicting Supreme Court decisions).

Unfortunately, the U.S. government saw InTrade as a form of online gambling. As such, it needed to be tightly regulated or perhaps even suppressed. It’s a complicated story — and may have involved “financial irregularities” on InTrade’s part — but, in 2013, InTrade decided to close its doors.

So, how can we use prediction markets in the United States? In its wisdom, another agency of the federal government, the Intelligence Advanced Reesarch Projects Activity (IARPA), started a prediction tournament called Aggregative Contingent Estimation (ACE). IARPA/ACE has run a prediction tournament for the past three years. Various teams – mainly from academic institutions – participate for the honor of being named the most accurate forecaster.

And who wins these tournaments? A team called The Good Judgment Project (GJP) put together by none other than Philip Tetlock. GJP selects several thousand volunteers, gives them some training on how to make forecasts, and asks them to forecast the several hundred questions included in the IARPA/ACE tournament.

The Good Judgment project wins the tournament consistently. They must be doing something right. And who is the newest forecaster on the Good Judgment team? Well… with all due modesty, it’s me.

To say the least, I’m excited to participate – and I expect to write about my experiences over the coming months. I can predict with 70% confidence that I won’t be a world class forecaster in the first go round. But I may just learn a thing or two and improve my accuracy over time. Wish me luck.

When Should You Name Your Baby?

University of Guanajuato

In 1980, Suellen and I moved to Mexico where I was invited to teach at the University of Guanajuato. A lovely mountain town about 200 miles northwest of Mexico City, Guanajuato is rich in history, culture, and tradition. It’s the heart of the Bajío, a broad, fertile region known as the breadbasket of Mexico. Graham Greene’s novel, The Power and The Glory, uses the Bajío as a backdrop.

My students were in their twenties and getting married and having babies. During our year in Guanajuato, Suellen and I were invited to any number of “baby welcoming” parties. About a month after a baby arrived, the parents would host a party to introduce the baby to family, friends, and neighbors. It was like being a very small debutante.

The parties were quite touching. Attendees took note of the fact that a new member of the community had arrived. We implicitly agreed to help the child grow and prosper. We also told stories, offered advice, and gave presents.

At many of the parties, the baby did not yet have a name. I often asked about this: “Why haven’t you named the baby yet?” The more-or-less standard response: “We’ve only just met him. We need to live with him for a while to learn which name fits him best.”

I sometimes noted that, in the United States, we typically named our babies well before they arrived. To which one of my students remarked, “No wonder you gringos are so screwed up. You all have the wrong names!”

So when should you name your baby? It was a question I had never considered before… and that’s the point here. A central tenet of critical thinking is that we should question our own assumptions. As the world has changed, have our assumptions changed as well? Are they still valid? Were they ever?

But how do you question your assumptions if you don’t realize that you’re making assumptions? I assumed that one should name a baby before it arrives. I never questioned it. Why would I? It’s the natural order of things, isn’t it?

So, how do you uncover your unknown assumptions? Here are a few things that have worked for me:

- Learn a new language – many assumptions are bound up in our language; especially the metaphors we use. Learn a new language and you’ll pick up new metaphors and identify hidden assumptions.

- Travel to a different country – paraphrasing Yogi Berra, you can learn a lot just by observing.

- Talk to people who aren’t like you – living in a diverse community (or working in a diverse company) helps you think more clearly. You probably won’t suffer from groupthink.

- Study history – it’s amazing what people used to think.

- Ask yourself a simple question – why do I think that?

Questioning your assumptions doesn’t necessarily mean that you should change them. You may find that they still work quite well. We didn’t change our baby naming assumptions, for instance. We named Elliot well before he arrived and he turned out just fine (I assume).

Innovation Assimilation

Next?

In 1983, when I was a product manager at NBI, we were second only to Wang in the word processing and office automation market. Then along came the personal computer and disrupted Wang, NBI, CPT and every other vendor of dedicated word processing equipment.

I’ve written about this previously as an example of disruptive innovation. But I could also describe it as assimilative innovation. NBI’s products did one thing – word processing — and did it very well. The PC, on the other hand, was multifunctional. It could do many things, including word processing (although not as well as NBI). The multifunction device assimilated and displaced the single function device.

We’ve seen many examples of assimilative innovation. When I bicycled across America, I bought a near-top-of-the-line digital camera to record my adventures. It took great pictures. It still takes great pictures. But I hardly ever use it. My smartphone does a lot of things, including taking great pictures. Though my smartphone’s pictures are not as good as my camera’s, they’re good enough. Additionally, the smartphone is a lot more convenient.

Years ago, the automotive industry produced an odd example of innovation assimilation. American cars had a big hole in the dashboard (fascia) where you could slot in a radio and cassette player. You were supposed to buy the audio equipment from the car manufacturer but consumers quickly figured out that they could get it cheaper from after-market vendors.

So, did the auto manufacturers lower their prices? No way, Instead, they re-designed their dashboards so that the audio equipment came in several pieces that an after-market vendor couldn’t easily mimic. In other words, the manufacturers tired to assimilate the competition.

In this case, it didn’t work. The after-market vendors sued, claiming illegal restraint of trade. The courts agreed and ordered the manufacturers to go back to the big hole in the dashboard. I suspect this was a precedent when Nestlé sued to stop third-party vendors from selling coffee capsules for the popular Nespresso coffee maker. Nestlé lost. The courts ruled that Nestlé had created a platform that allowed for permisionless innovation.

What will be assimilated next? I suspect it’s going to be fitness bands. I wear the Jawbone band on my wrist to keep track of my activity and calories. It’s pretty good and seems to compete well with three or four other fitness bands on the market. The new Apple Watch, however, appears to have similar (or even better) functionality built into it. The Apple Watch is, of course, multi-functional. If history is any guide, the multi-functional and convenient device will displace the single purpose device, even if it doesn’t offer better functionality.

What’s the moral? When you buy a single function device, be aware that it’s likely to be assimilated into a multi-function device in the future. That’s not a bad thing as long as you’re aware of the risk.

How Are You? Your Keyboard Knows.

Know-it-all.

Some months ago I took an online course — a MOOC — offered through Coursera. To identify me, Coursera’s security system asked me to type in approximately three sentences of text. Whenever the system needed to identify me again, it sampled my keystrokes. It could tell by the way I type that I was indeed the one and only G. Travis White.

That’s a pretty neat trick. The Coursera system doesn’t need to read my fingerprint or do an eye scan. It just needs to observe my typing skills. The system can easily distinguish me from all the other students in class and, conceivably, from every other human on earth. It’s simple, cheap, and hard to mimic.

So, what else can a keyboard do? Normally, when we interact with a computer, we’re transferring information. We’re asking questions and receiving answers. We’re issuing command and expecting responses. Whether we type fast or slow or hard or soft, we expect the computer to react the same way to the same input. We’re transferring information and nothing else.

But if a keyboard can uniquely identify us, could it also do more? Could it detect our emotions? And, if so, could it change the computer’s behavior based on the emotions it detects?

These are questions that several researchers at the Islamic University of Technology in Bangladesh investigated in an article recently published in Behaviour & Information Technology. As the authors point out, “Affective computing is the field that detects user emotion… [and if a machine]… can detect user emotions and change its behavior accordingly, then using machines can be more effective and friendly.”

So, how do you teach a machine to detect emotions? The researchers chose keystrokes for the same reasons that Coursera did: they’re cheap and available. The researchers also chose to combine two different methods of analysis that had previously been studied:

- Keyboard dynamics – including dwell time (how long your finger stays on a key), flight time (how long it takes to get to the next key), and content attributes (number of deletes, backspaces, etc.).

- Text pattern analysis – this usually involves identifying “affective content” by spotting specific keywords and analyzing syntax as the user chats with other users.

The researchers aimed to identify seven different emotions – anger, disgust, fear, guilt, joy, sadness, and shame as defined in the International Survey on Emotion Antecedents and Reactions (ISEAR).

And how did it work? Remarkably well. Using the two methods together produced better results than either method independently. Better yet, the results were surprisingly consistent across the range of emotions. Here’s how often the system detected an emotion correctly:

Joy 87%

Anger 81%

Guilt 77%

Disgust 75%

Sadness 71%

Shame 69%

Fear 67%

What’s next? How about a computer that responds to your emotional state by changing its behavior in a variety of subtle and not-so-subtle ways? In other words, it becomes a true personal assistant rather than merely mechanical device. Imagine the possibilities.