The Structure of Predictions

I like to think about the future. So, in the past, I’ve written about scenario planning, prediction markets, resilience, and expert predictors. What have I learned in all this? Mainly, that experts regularly get it wrong. Also, that experts move in herds — one expert influences another and they begin to mutually reinforce each other. In the worst cases, we get manias, whether it’s tulip mania in 17th century Holland or mortgage mania in 21st century America. Paying ten times your annual income for a tulip bulb in 1637 is really not that different from Bank of America paying $4 billion for Countrywide.

I’ve also learned that you can (sometimes) make a lot of money by betting against the experts. The clearest description of “shorting” the experts is probably The Big Short by Michael Lewis.

I’m also forming the opinion that the reason we call people “experts” is because they study problems closely. They’re analysts; they study the details. Like college professors, they know a lot about a little. That may make them interesting dinner partners (or not) but does it make them better predictors of the future?

I’m thinking that the experts’ “close read” makes them worse predictors of the future, not better. Why? Because they go inside the frame of the problems. They pursue the internal logic of the story. Studying the internal logic of a situation can be useful but, as I pointed out in a recent article, it can also lead you astray. In addition to the internal logic, you need to step outside the frame and study the structure of the problem. If you stay inside the frame, you may well understand the internal dynamics of the issue. But, in many cases, the external dynamics are more important.

The case that I’ve been following is the cost of healthcare in the United States. The experts all seem to be pointing in the same direction: healthcare costs will continue to skyrocket and ultimately bankrupt the country. The experts are pointing in one direction so, as in the past, I think it’s useful to look in the other direction and predict that healthcare costs won’t climb as rapidly as in the past or may even go down.

Here are two interesting pieces of evidence that suggest that the experts may be wrong. The first is a report from the Altarum Institute which notes that 2012 represented the “…fourth consecutive year of record-low growth [in healthcare spending] compared to all previous years in the 50-plus years of official health spending data.” Granted, there’s a debate as to whether the slowing growth is caused by the recession or by structural changes but the experts (yikes!) suggest that at least some of the shift is structural.

The second piece of evidence is a report by Matthew Yglesias in Slate that documents the dramatic decline in spending for healthcare construction. Spending to construct new hospitals dropped precipitously in 2008 and has stayed low, even during the recovery. As Yglesias points out, construction spending is “the closest thing we have to a real-time forecast of what the future is going to look like.”

So, are the experts wrong? As Chou En Lai liked to say, it’s too soon to tell. But let’s keep an eye on them. Otherwise, we could be framed.

Premature Commitment. It’s a Guy Thing.

There’s a widespread meme in American culture that guys are not good at making commitments. While that may be true in romance, it seems that the opposite — premature commitment — is a much bigger problem in business.

That’s the opinion I’ve formed from reading Paul Nutt’s book, Why Decisions Fail. Nutt analyzes 15 debacles which he defines as “… costly decisions that went very wrong and became public…” Indeed, some of the debacles — the Ford Pinto, Nestlé infant formula, Shell Oil’s Brent Spar disposal — not only went public but created firestorms of indignation.

While each debacle had its own special set of circumstances, each also had one common feature: premature commitment. Decision makers were looking for ideas, found one that seemed to work, latched on to it, pursued it, and ignored other equally valid alternatives. Nutt doesn’t use the terminology, but in critical thinking circles this is known as satisficing or temporizing.

Here are two examples from Nutt’s book:

Ohio State University and Big Science — OSU wanted to improve its offerings (and its reputation) in Big Science. At the same time, professors in the university’s astronomy department were campaigning for a new observatory. The university’s administrators latched on to the observatory idea and pursued it, to the exclusion of other ideas. It turns out that Ohio is not a great place to build an observatory. On the other hand, Arizona is. As the idea developed, it became an OSU project to build an observatory in Arizona. Not surprisingly, the Ohio legislature asked why Ohio taxes were being spent in Arizona. It went downhill from there.

EuroDisney — Disney had opened very successful theme parks in Anaheim, Orlando, and Tokyo and sought to replicate their success in Europe. Though they considered some 200 sites, they quickly narrowed the list to the Paris area. Disney executives let it be known that it had always been “Walt’s dream” to build near Paris. Disney pursued the dream rather than closely studying the local situation. For instance, they had generated hotel revenues in their other parks. Why wouldn’t they do the same in Paris? Well… because Paris already had lots of hotel rooms and an excellent public transportation system. So, visitors saw EuroDisney as a day trip, not an overnight destination. Disney officials might have taken fair warning from an early press conference in Paris featuring their CEO, Michael Eisner. He was pelted with French cheese.

In both these cases — and all the other cases cited by Nutt — executives rushed to judgment. As Nutt points out, they then compounded their error by misusing their resources. Instead of using resources to identify and evaluate alternatives, they invested their money and energy in studies designed to justify the alternative they had already selected.

So, what to do? When approaching a major decision, don’t satsifice. Don’t take the first idea that comes along, no matter how attractive it is. Rather, take a step back. (I often do this literally — it does affect your thinking). Ask the bigger question — What’s the best way to improve Big Science at OSU? — rather than the narrower question — What’s the best way to build a telescope?

Circuses and Oceans

The first time we went to Cirque de Soleil, we took Elliot and a bunch of his 12-year-old buddies. After all, circuses are for kids, right? As it turned out, Suellen and I enjoyed the show just as much — maybe more — than the kids did. I didn’t expect that.

Cirque de Soleil is an excellent example of a mashup innovation. Traditional circuses were for kids. I remember going to Ringling Brothers with my folks. I was dazzled by Uno — the man who could do a handstand on one finger. My parents were troupers but I don’t think they were dazzled. They took me because … well, circuses are for kids.

On the other hand, Broadway musicals are from grownups. They have a bit of a story to follow, they have some conflict, perhaps some mushy stuff, and a resolution. Most of all they have singing. This is where young kids start squirming. I mean, really … how many seven-year-olds want to know that when you’re a Jet, you’re Jet all the way?

The genius of Cirque de Soleil is that it mashes up the traditional circus — get the kids — with Broadway musicals — bring the grownups, too. There’s enough of a story to appeal to Mom and Dad and enough cool (and weird) stuff to appeal to seven-year-olds. It’s family entertainment for modern city dwellers.

While Cirque is a great mashup story, it may be more than that. According to W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, it’s also a great example of a Blue Ocean Strategy. For Kim and Mauborgne, there are red oceans and blue oceans. A red ocean is full of the blood of competitive strife — it’s red in tooth and claw. The red ocean represents a market of a given size. It’s not going to get any bigger so the only way for one company to grow is to make another company shrink. Strategy is all about defeating the competition rather than winning the customer. As Kim and Mauborgne point out, the market for traditional circuses was very much a red ocean.

A blue ocean, on the other hand, allows you to jump beyond the competition. You create something new and, in doing so, you create a new market where your traditional competitors are irrelevant. The authors offer some great examples of blue ocean strategies and some intriguing and very instructive tips for how to develop one. For Kim and Mauborgne, the genius of Cirque de Soleil is that they have leapt out of the red ocean and into a blue ocean where they rule the waves. Indeed, they’re the only ship in sight.

I’ll report on more blue ocean examples in future posts. At the same time, however, I have a nagging feeling that a blue ocean is not that different from the classic marketing strategy of creating a new category. Once upon a time, for instance, sedans were practical but not much fun to drive. (For my British readers, what Americans call a sedan, you call a saloon). On the other hand, sports cars were fun to drive but not very practical. Then BMW mashed up the two categories and created a sports sedan — practical yet fun to drive. Was the BMW sports sedan a new category or a blue ocean? I’ll report more on that in the future. No matter what you call it, however, mashups are a great way to get there.

Seven Strategies (But Not For Success)

What strategies don’t work? I had been trying to organize bad strategies into a mental map when I came across an article in The Economist that did the heavy lifting for me. In its own pithy way, The Economist names and shames six strategies that just don’t work. To that, I’ll add a seventh.

What strategies don’t work? I had been trying to organize bad strategies into a mental map when I came across an article in The Economist that did the heavy lifting for me. In its own pithy way, The Economist names and shames six strategies that just don’t work. To that, I’ll add a seventh.

Here are The Economist’s six along with my own pithy observations.

The Do-It-All strategy — don’t make the hard product choices. When you find market opportunities, pursue all of them. If you build enough products, something is bound to sell. This is sometimes known as the Food-Fight strategy — throw a bunch of food at the wall and see what sticks.

The Don Quixote strategy — launch a frontal attack on your strongest competitor. Take the fight right to them. It sounds bold — and everybody wants to be bold these days — but it’s well nigh suicidal. Its main advantage compared with the Do-It-All strategy: it’s over quickly. As Sergeant York taught us, don’t fire at the lead goose in the flying wedge. Fire at the last one and work your way forward.

The Waterloo strategy — fight on too many fronts at once. Rather than carving up the battlefield to your advantage, attack multiple enemies at once. That’ll teach ’em. Just like at Waterloo.

The Something-for-Everyone strategy — what’s our target market? Anyone who has money. This is often found in combination with the Do-It-All strategy. We’ve got lots of products, so let’s find lots of customers. One of the strengths of Lawson Software’s strategy is that we were very clear about who we served and who we didn’t. We turned down prospective customers who didn’t fit our profile. We couldn’t serve them successfully without distracting attention from our priority customers.

The Programme-of-the-Month strategy — first it was Pursuit of Excellence, then it was Built to Last, then it was … well, whatever the latest hot business book is. We’re dedicated to pursuing the fashionable strategy of the moment. Better to pick a simple strategy and stick with it.

The Dreams-That-Never-Come-True strategy — ambitious mission statements are never translated into clear choices. At some point, you have to come down out of the clouds and pursue this market (as opposed to that one) with this plan (as opposed to that one). It’s about making choices.

To The Economist Six, I’ll add a seventh:

The Military/Territorial strategy — the market is like a piece of territory that multiple armies are fighting over. There’s only so much territory; it can’t be expanded. If a competing army wins more of it, we will win less of it. It’s a zero sum. We have to stay focused on the competition and counter every maneuver. It’s a popular analogy but a bad one. War is about defeating the enemy. Business is about winning the customer. Focusing on the competition won’t get you there.

As I’ve written before, strategy is about what you don’t do. It’s about making hard choices that allow you to focus on markets or products or customers where you have the greatest chance of success. Forget everything else.

Strategy: Five Components

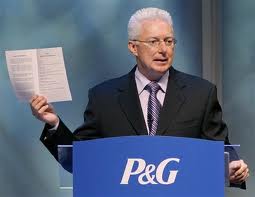

A.G Lafley is justifiably famous for taking over Procter & Gamble (P&G) and converting an insular company into a customer-centric, outward-looking culture known for a string of successful innovations. When Lafley became CEO in 2000, innovation was driven by thousands of in-house R&D designers, researchers, and engineers. They created neat stuff and “pushed” it to customers. Partially as a result, P&G’s success rate with new products and brands hovered around 15%. The R&D teams focused internally; only about 10% of new products came from outside the company.

Lafley essentially turned the company inside-out by putting the customer at the head of the innovation process. P&G called it Connect + Develop and emphasized collaboration with other departments, customers, and even outside research organizations. Lafley changed the culture from “not invented here” to “proudly found elsewhere”. P&G signed more than 1,000 collaborative agreements with outside organizations. It was a fundamental cultural change and the results were spectacular. According to a report from A.T. Kearney, “During Lafley’s tenure, sales doubled, profits quadrupled, and the company’s market value increased by more than $100 billion”.

Now Lafley has written a book, Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works, with Roger Martin, the Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the Univeristy of Toronto. Martin was Lafley’s “principal external strategy advisor”. In addition to Martin, Lafley built a brain trust of outside thinkers including designers and business professors. The eclectic nature of the group created many different “idea collisions” that generated process innovations as well as product innovations.

I’m sure that I’ll write a lot about the book in the future but it’s not quite out yet. It debuts in February. Today, I’m depending on the report from A.T. Kearney and a lengthy review from The Economist. One of the key insights is that P&G followed a strategy composed of five elements, each designed to help managers make the right decisions. These are:

- What does winning look like? What are we aiming for and what information do we look for along the way to help us understand if we’re making progress? Do we seek global domination, regional, or local?

- Which markets should we play in? Of course, this also implies another question: which markets should we ignore (or exit)? How do we determine which is which?

- How do we win? What’s our distinctive strategy in each market and category?

- What are our strengths and weaknesses and how do we deploy them in each market, against each competitor?

- What needs to be managed for the strategy to succeed? Of course, the inverse of this question is what doesn’t need to be managed? The Economist reports that one of Lafley’s “most important innovations was a slimmed-down strategy-review process … [that] replaced needlessly sprawling bureaucratic meetings….”

It’s a good story and an intriguing look at strategy. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have an entirely happy ending. The Economist reports that P&G has “stumbled badly” since Lafley left in 2009. Similarly, Martin’s consulting firm “got into financial difficulty and has been sold at a discount.” Still, the questions are relevant to any company’s strategy and the story is intriguing. I’ll report more soon.