Baseball, Big Data, and Brand Loyalty

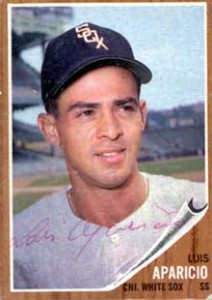

My hero.

I started smoking in high school but didn’t settle on “my” brand until I got to college. My Dad smoked Camels for most of his life but I decided that was not the brand for me. (Cough, hack!) Ultimately, I settled on Marlboros.

How I made that decision is still a mystery to me. In its very earliest days, Marlboro was positioned as a “woman’s brand” with slogans like “Ivory tips protect the lips” and “Mild as May”. That didn’t work very well, so the brand changed its positioning to highlight rugged cowboys in the American west. The brand took off and along the way I got hooked.

Though I don’t know why I chose Marlboros, I do know that it was a firm decision. I smoked for roughly 20 years and I always chose Marlboro. This is why brand owners focus so much attention on the 18-to-24 year-old segment. Brand preferences established in those formative years tend to last a lifetime.

But brand preferences often form quite a bit earlier. Brand owners may actually be late to the party. For example, I chose my baseball team preferences when I was much younger.

I played Little League baseball and was crazy about the sport. In our league, the teams were named after big league teams. Even though we lived in Baltimore, I played shortstop and second base for the Chicago White Sox. (The book on me: good glove/no bat).

At the time, Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox played shortstop and second base for the real Chicago White Sox. They were my heroes. I knew everything about them, including the fact that they both weighed about 150 pounds in the pre-steroid era. I formed an emotional connection with the White Sox at the age of 10 or 11 and I still follow them.

My brand loyalty even rubbed off on the “other” team in Chicago, the Cubbies. Their shortstop was the incomparable Ernie Banks. I had heard of the Holy Trinity and I assumed that it was composed of Luis, Nellie, and Ernie.

I thought about all this when I opened the New York Times this morning and read about the nexus of Big Data, Big League Baseball, and Brand Development. Seth Stephens-Davidowitz has used big data to probe fan loyalty to various major league teams. (Unfortunately, he omits the White Sox).

Among other things, Stephens-Davidowitz looks at fans’ birth years and finds some interesting anomalies. For instance, an unusually large number of New York Mets fans were born in 1961 and 1978. Why would that be? Probably because boys born in those years were eight years old when the Mets won their two World Series championships. Impressionable eight-year-old boys formed emotional attachments that last a lifetime.

How much is World Series championship worth? Most brand valuations focus on how a championship affects seat, television, and auxiliary revenues. Stephens-Davidowitz argues that this approach fundamentally undervalues the brand because it omits the value of lifetime brand loyalty. When he recalculates the value with brand loyalty factored in, he concludes that “A championship season … is at least twice as valuable as we previously thought.”

What’s a brand worth? As I’ve noted elsewhere, it’s hard to measure precisely. But we form emotional attachments at very early ages and they last a very long time. As Stephens-Davidowitz concludes, “…data analysis makes it clear that fandom is highly influenced by events in our childhood. If something captures us in our formative years, it often has us hooked for life.”

The Brighter Side of Spite

In the dumpster?!

In October 2013, a Boulder, Colorado man took some half million dollars out of savings, converted it to gold and silver bars and threw them in a dumpster. What would account for such behavior? Spite. After a bitter divorce, the man didn’t want his ex-wife to get any of the money.

Spite has a long history. As Natalie Angier points out, spite is the driving force behind the Iliad. Achilles wants revenge on Agamemnon, even though it will be very painful to Achilles as well.

Spite is similar to altruism but with a different purpose. An altruistic person pays a personal price to do something helpful to another person. A spiteful person pays a personal price to do something hurtful to another person.

Spitefulness sometimes feels good. You’re getting even; you’re teaching the other person a lesson. But it rarely does any good. Does the other person really learn a lesson – other than to despise you? With spite, both parties lose. So, why does spitefulness stick around?

It could be a form of altruistic punishment. Altruism isn’t always positive for everyone concerned. You might punish somebody — and pay a price to do so — in order to bring a greater good to a larger community. In this sense, altruistic punishment is simply spite for the greater good.

A study by Karla Hoff in 2008 used a “trust game” to probe this phenomenon. In the game, trusting players can earn more money by giving away money. But a “free rider” (also known as an opportunist) could take advantage of the trusting player, hoard the money, and come out ahead. The game uses an “enforcer’ who can choose multiple options, including various punishments for the free rider.

Punishing the opportunist costs the enforcer. Still, in many cases enforcers decided to do just that. By spiting the free rider, the enforcer adds a cost to anti-social behavior. As opportunism become more costly, it also becomes less pervasive. Ultimately the enforcer’s spite encourages cooperation. It’s good for the community even though it hurts the enforcer. (This was a complex study and altruistic punishment varied by culture and by the social status of the various players).

More recently, Rory Smead and Patrick Forber used an “ultimatum game” to study spite and fairness. In some versions of the game, “gamesmen” emerge who make only unfair offers. Other players will spite the gamesman. Even though they pay a cost in the short run, fair players who spite the gamesman can benefit in the long run. Indeed, “Fairness actually becomes a strategy for survival in this land of spite.”

How do you measure spitefulness? David Marcus and his colleagues have developed a 17-point Spitefulness Scale “…to assess individual differences in spitefulness.” They then applied it across a large random sample of college students and adults. They found (among many other things) that men are generally more spiteful than women and young people are more spiteful than older people. Spitefulness is positively correlated with aggression and narcissism but negatively correlated to self-esteem. The researchers are now going to use the scale to predict how different players will act in trust and ultimatum games.

I’ve previously written about seemingly “good things” that produce bad outcomes. Spite is a good example of a “bad thing” that can produce good outcomes. Not always and not in all situations, but more often than we might guess. It’s useful to keep in mind that, if something exists, it often does so for a good reason.

Liar, Liar, Confabulator

Uh oh. His lips are moving.

How can you tell when humans are lying? Their lips move.

It’s not necessarily the case that we lie with the intent to deceive or defraud. It’s just that many of the stories that come out of our mouths simply aren’t true. You can call it non-malicious fabricated storytelling. More generally, it’s called confabulation.

Neurologists originally thought confabulation resulted from mental deficits caused by injuries or strokes or dementia. People with such deficits might tell entirely cohesive stores that were simply not true. Some people might recall old memories and assume that they were fresh and current. Others might invent stories to explain their physical limitations like blindness or paralysis. In Oliver Sack’s well-known book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, the man in question mis-identified not only his wife but most everyone he met.

The more we study confabulation, the more we recognize that “normal” people do it as well. We all have an innate desire to connect the dots. We want to explain how things happen and why. We want to be able to say that X caused Y and – if it was true in the past – it should also be true in the future.

The more we can construct effective stories about the past, the more we believe we can control the future. This gives us a sense of confidence and security. But, of course, we can’t predict the future. (Experts are especially bad at it). I wonder if our inability to predict the future doesn’t result from confabulation. We confabulate the past and, therefore, the future.

Here’s a little thought experiment. If you see five similar objects arrayed left to right, which one do you prefer? In the absence of distinguishing information, people tend to pick the object on the right. Richard Nisbett and Timothy Wilson used this bias in an early study of “normal” confabulation. The study simulated a consumer survey and asked subjects to pick an item of apparel from a left-to-right array of four items that were essentially the same.

Nisbett and Wilson noted that, “… the right-most object in the array was heavily over chosen.” This was expected; it’s normal behavior. However, when the researchers asked people why they chose a particular object, they gave all kinds of answers that had nothing to do with position. In other words, they were confabulating even under perfectly normal conditions.

Similarly, I have a story that explains my career. I have an explanation for why I was promoted in a certain case and not in another. I can explain how I got from Job A to Job G in a very linear, logical fashion. But do I really know these things? Am I really sure what caused what? Do I really know why the boss made a given decision? No, I don’t. But I can make up a good story.

The only way to prove cause-and-effect is through an experiment. I would have to replicate myself and run the two versions of me in parallel. I obviously can’t do that, so I’ve made up a convenient story. It seems plausible; it works for me. But is it true? Even I don’t know.

Confabulation happens before and beneath our consciousness. Nisbett and Wilson cite George Miller: “It is the result of thinking, not the process of thinking, that appears spontaneously in our consciousness.” We can’t readily control confabulation because we don’t know it’s happening. We only see the results.

When you ask someone a question like, Why did you choose your career? (or your spouse, or your suit, etc.), you’ll likely get a plausible answer. But is it true? Even the speaker can’t know for sure. Can it help us understand the past and predict the future? Probably not.

For a good overview of confabulation, see Helen Phillips’ article in New Scientist.

Are Computers Funny?

Pretty funny for a computer.

My friends sometimes say that they can’t tell if I’m joking or not. I wonder if they’re more like computers than we might like to think.

As you may know, computers can actually create jokes. They have a much more difficult time identifying jokes. Sort of like some of my friends.

Constructing a joke often means following a pattern and, as we know, computers are pretty good at following patterns. As Margaret Boden points out, , “Humor is essentially a matter of combinatorial creativity.” Scott Weems seconds the notion, “When we create a joke we’re not inventing new thoughts or scripts, we’re connecting ideas in new ways.”

We’ve seen this before with innovation and creativity. Some of our most successful innovations are mashups of two or more relatively prosaic ideas. Rather than thinking outside the box, we pull old ideas from multiple boxes and combine them in new ways. The wheel is not a new idea. Nor is luggage. Only recently did we think to combine the two to create wheeled luggage.

Can a computer combine ideas in a humorous way? Well, sure. This morning I created about a dozen new jokes using the Joking Computer on the University of Aberdeen website. Here are the two best ones:

What do you call an American state that has a lip? Mouth Carolina.

What’s the difference between aluminum foil at noon and an amusing garden? One is a sunny foil; the other is funny soil.

They both follow a pattern involving rhymes, word substitutions, puns, and antonyms. I doubt that either one of them made you laugh out loud but they’re kind of cute.

Then I went to the Humorous Agent for Humorous Acronyms – HAHAcronym – website. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to be active any more. I found two things humorous about this project. First, it could generate acronym definitions like:

MIT – Mythical Institute of Theology

FBI – Fantastic Bureau of Intimidation

Second, the project was funded by the European Union. Can you imagine the U.S. Congress funding something similar? It would almost certainly win a Golden Fleece award.

You may think that these software programs are not clever at all. They simply repeat a pattern. But we humans often follow similar patterns (sometimes called scripts) to create humor. Here’s one that I learned long ago and still use on occasion:

You can make most any sentence mildly funny by appending to it one of two endings:

….., said the Bishop to the chorus girl. Or

….., said the chorus girl to the Bishop.

So, are we no better than computers? In some forms of joke production, we’re similar. But there are many forms of joke production. But the big difference is joke recognition and appreciation. Weems provides an example of a joke that we would get but a computer wouldn’t:

He is so modest that he pulls down the shades before changing his mind.

Why wouldn’t a computer get it? Because a computer doesn’t have world knowledge. It doesn’t understand that you might pull the shades before changing your clothes but that changing your mind is quit a bit different than changing your clothes.

Will computers ever catch us in humor appreciation and production? I suspect they will and fairly soon as well. I was surprised at how quickly computers solved the problem of driving cars. Or of grading essays almost as well as I can. It shouldn’t be long before computers can actually make us LOL.

Laughtivism

Can laughter change the world? I’d like to think so. That seems to be the basic motivation behind an increasingly popular form of activism known as laughtivism. According to Foreign Policy magazine, “Today’s non-violent activists are inciting a global shift in protest tactics away from anger, resentment, and rage towards a new, more incisive form of activism rooted in fun.”

Can laughter change the world? I’d like to think so. That seems to be the basic motivation behind an increasingly popular form of activism known as laughtivism. According to Foreign Policy magazine, “Today’s non-violent activists are inciting a global shift in protest tactics away from anger, resentment, and rage towards a new, more incisive form of activism rooted in fun.”

Plato, of course, banished humor and laughter from The Republic. He thought humor would distract the populace from the more serious issues of the day. Today’s laughtivists turn that logic on its head. The world is malign and malevolent; laughter is the only cure.

The phenomenon (I hesitate to call it a movement) is widespread. Beppe Grillo is one of the most popular and incisive politicians in Italy. Srdja Popovic used humor in opposition to a man who never seemed to smile, Slobodan Milosevic. Bassem Youssef in Egypt is widely known as the Arab Jon Stewart. The Yes Men have now made two films aimed at raising awareness of “problematic social issues.” And, of course, Jon Stewart is widely known as the American Bassem Youssef.

Laughtivism aims at political enlightenment and activism by undermining the legitimacy of ruling elites, especially those that scowl. I mean, really, how hard is it to make fun of Dick Cheney?

It’s also spiritually akin to culture jamming, which aims more broadly at undermining the established culture and mainstream media. As Wikipedia notes, culture jamming “purports to ‘expose the methods of domination’ of mass society to foster progressive change.” As such, laughtivism harks back to Abby Hoffman, the Yippies (with their nude radio show), Dr. Strangelove, and, perhaps, even to Marshall McLuhan.

Laughtivism aims to speak truth to power. That’s all well and good, but as Kei Hiruta points out in Practical Ethics, laughter “can also be used to conceal truth and reinforce cynicism.” We’ve all heard racist or sexist or homophobic jokes that aim to do exactly that.

While I enjoy laughtivism, I wonder how effective it is in changing the social order. For instance Yes! Magazine identified “Five Protests That Shook The World (With Laughter)”. Here’s how it describes the protest it ranks as number one:

In 1967, Abbie Hoffman and members of the Yippies, a radical activist group, threw 300 one-dollar bills from the New York Stock Exchange balcony onto the trading floor. According to Hoffman, as brokers grabbed for petty cash, trading ground to a halt. The famous stunt mocked the unregulated greed that still pervades Wall Street.

I happen to remember that protest. I laughed very hard and admired Abby Hoffman very much. But did it really change anything? I’m sure that it inspired some people and enraged others, but I didn’t see the pillars of society waver even a tiny bit.

Aristotle and other Greek rhetoricians taught that humor can help us learn and remember but that it doesn’t motivate us to take action. Humor can inspire and educate and even go viral but it doesn’t get us off the couch. Anger is the emotion that motivates action, which is precisely why our political rhetoric is so filled with anger.

I admire laughtivism because it can open a crack in the social facade. But I don’t think it has the force to drive the wedge home. As Hiruta says, “Mockery, jokes and satire are powerful tools to destabilise the existing order, but they are ill-suited to the different tasks of ending chaos, filling a power vacuum and installing a new order.”