An Evolutionary View of Innovation

My sister has a Ph.D. in biology. For her dissertation, she randomly divided fruit flies into two groups and treated them exactly the same except for one variable. She introduced a specific chemical to one group but not the other. Then she followed the effects through multiple generations. I don’t remember what she discovered but her method allowed her to conclusively link cause to effect.

My sister has a Ph.D. in biology. For her dissertation, she randomly divided fruit flies into two groups and treated them exactly the same except for one variable. She introduced a specific chemical to one group but not the other. Then she followed the effects through multiple generations. I don’t remember what she discovered but her method allowed her to conclusively link cause to effect.

Why did she choose fruit flies? Because she wanted to look at the effects of the chemical over multiple generations and fruit flies create generations quickly. She wanted to know not just how the chemical affected fruit flies. She wanted to know how the chemical affected the evolution of fruit flies.

Could we use evolutionary thinking to solve business problems in innovative ways? Well, there’s a theory that we could develop software more quickly and at less expense through evolutionary techniques.

First we identify a problem that we want software to solve. Then we create, say 10,000 identical sets of code. We introduce random variations into each set, execute the code, and then determine which set comes closest to solving the problem. We take the winner, make 10,000 copies, introduce random variations into each one, then execute the code. We pick the winner and repeat the process. It’s like breeding dogs, only less messy.

With modern computing power, we can generate thousands of generations in very short order. We could almost certainly solve the problem. Additionally, we might generate some very novel solutions. The random variation might lead us down paths that we never would have imagined on our own.

While I suspect we’ll make evolutionary software before long, it does seem a bit exotic. Are there ways we could apply evolutionary thinking to solve more practical, day-to-day problems?

Sometimes I think it’s as simple as asking the question. Too often we make yes/no, either/or decisions – whether-or-not decisions as Chip Heath calls them. But we can always ask the question, is there an evolutionary way of looking at the problem? We might find that there are multiple sub-decisions we could make along the way to the big decision. We can decide smaller issues, test the results, and repeat the process. Each time we do, we create a new generation.

A “generation” in this sense might be a set of market trials, a series of studies, or surveys, or focus groups, or trial balloons. We can find many ways to identify and/or validate market needs. But first we have to ask the question. So the next time you participate in a big decision – especially a big risky decision – be sure to ask yourself, could an evolutionary approach help us here? The answer may be no, but don’t close the door too soon.

Should We Work?

What? I still have to work?

Which of these two government policies is most appropriate for the next 50 years?

- Strive to reduce unemployment; aim for 4% unemployment.

- Eliminate the need to work; aim for 100% unemployment.

It’s a question we’ll need to wrestle with soon. It appears that we’re at the beginning of another great wave of job destruction. The last wave, starting roughly in 1980, eliminated or outsourced blue collar and clerical jobs. We used to have secretaries; now we have word processing software. We used to have factory workers; now we have robots.

The next wave will eliminate white collar jobs. This will happen in two ways:

Type 1 – through advanced communications and software support, a small number of “augmented knowledge workers” can do the work of thousands of traditional knowledge workers.

Type 2 – machines and systems will become smart enough to replace many knowledge workers.

I’ll illustrate with two examples from my life.

Type 1: The MOOCs. Massive Online Open Courses find very talented professors and augment them. With video, web, and online testing support, these professors can literally reach thousands of students. They give great lectures. (You should watch them). Why do we need other professors to cover the same material? A few professors can replace thousands. By the way, this will also accelerate the dominance of English.

Type 2: Automated Essay Grading. I’m rather proud of my ability to read essays and make useful comments that help students think more clearly and communicate more effectively. So what? Within the next few years, we’ll see software systems that can do almost as good a job as I can. OK … maybe they could do it even better since they never get tired. I’ve always thought that this would be a difficult task to automate because it’s “fuzzy”. But computers are mastering fuzzy logic even as we speak.

Much of what we call “knowledge work” is actually easier to automate than essay grading. Any process based on rules is fairly easy to computerize. Deciding which stocks to buy or sell is a good example. It’s just a set of rules. So today, “quants” and high-speed computers dominate much of our stock trading.

Diagnosing an illness may be another good example. Today, as many as 15% of diagnoses made by humans are wrong. But diagnosis is just a rules-based process. Surely, a computer can do better.

Within the next three decades, we may well reach a point where nobody needs to work. So what will we do? Good question. Perhaps we should ask a computer.

Crowd Sourcing Your Mail

You’ve got chain mail.

Let’s say you want to send a package to my personal trainer, Alison. If you know two facts about me, you can have the package delivered for free. Fact 1: the local dairy delivers milk to my front door very early each Thursday morning. Fact 2: I see Alison every Thursday morning (after the milk is delivered).

So, if you could get the package to the dairy, the milkman could deliver it with my weekly supplies (without going out of his way). I could pick up the package (without going out of my way) and deliver it to Alison. Everybody is happy, nobody has gone beyond his or her normal routines, and the package is delivered quickly, efficiently, and cheaply.

How would you know those two facts about me? By following my Twitter feed. Yep, Twitter. By analyzing where my Twitter feeds come from, a system could conceivably track my whereabouts and predict where I might be at a given time. Theoretically, it could do this for thousands of people and plot an efficient series of hand-offs from one person to another. (I probably don’t tweet enough for this to work, but lots of people do).

The concept is known as TwedEx. It’s not here yet but it might soon be – you can read more about it here.

Here’s the creepy part, in my opinion. If a system can predict my movements based on my tweets, what can the government figure out based on the PRISM program?

MOOCs and Me – 1

Nothing’s changed.

As an adjunct professor at the University of Denver, I teach in University College (UCOL), the school’s professional and continuing education program. UCOL focuses on non-traditional students, especially people who have been out of school for some time and are returning to study for an advanced professional degree.

I teach at the Master’s level and most of my students are in their 30s and 40s. Many see the Master’s degree as a key to greater career opportunity. They’re mature and motivated. They’re focused on acquiring certified knowledge, not on growing up.

I teach my courses in two completely different formats: on campus and online. The on-campus courses meet one night a week. The online courses never meet at all – we interact with each other through a web-based electronic college.

I’ve taught on-campus courses off and on for many years. I know what I’m doing and I feel comfortable and confident in the classroom. On the other hand, when I started teaching online – two years ago – I felt very unsure of myself. Though I was very familiar with the technology, I didn’t know how to use it to teach effectively.

Two years later, I feel much more comfortable teaching through the web. In fact, in some ways, I prefer it. The major advantage is that I don’t have to be anywhere at any specific time. As long as I have an Internet connection, I can teach my class.

The same is true for my students. In my online classes, I typically have students in six to eight different states and two to three different countries. Through the magic of the web, I can potentially reach hundreds, even thousands of students.

And that brings us to MOOCs – the Massive Open Online Courses that are roiling college campuses across the country. MOOCs take some of some of our best professors — often from places like Stanford, MIT, and Harvard – put them in front of a camera and ask them to teach thousands of students across the web.

MOOCs are massive; some enroll 50,000 students or more. They’re open; anyone with an Internet tap can register. They’re also free. Yikes!

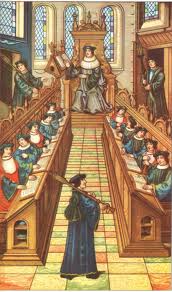

MOOCs challenge virtually everything we do in universities today. A fundamental problem of higher education is that it hasn’t increased productivity for 700 years or so. While every other industry has increased productivity and thus can offer more for less, higher education offers the same for more. Without productivity increases, tuition will always rise at least as fast as inflation.

MOOCs promise to change that. Put a great professor online and – presto! – we can educate the masses. We can also save a lot of money. Why should states pay millions to support brick-and-mortar campuses? Why should students spend thousands to attend schools with second-string faculty? Why indeed?

So, will MOOCs destroy academic life as we know it? Or will they be more like correspondence courses – an interesting niche but only a niche? As a teacher of MOOC-like courses, I do have an opinion. But, let’s talk about that tomorrow.

Snails and Innovation

What does a huge snail have to do with innovation? It’s all about the platform.

What does a huge snail have to do with innovation? It’s all about the platform.

The jungle – much like a coral reef – is an incredible platform for innovation. It creates an environment with billions of niches where flora and fauna can grow and evolve. There’s no particular plan, just a grand variety of nutrients. Ultimately, we get a cornucopia of life that we never could have predicted, even including a snail as big as your hand. (That’s Elliot’s hand in the photo, by the way, in the jungle of eastern Peru).

What’s the lesson here? We need to create more jungle-like platforms if we want to spur innovation. Platforms don’t have to be hot and steamy but they have to be rich in “mental nutrients” – food for thought. One of my favorite platforms, for instance, is the land-grant college system in the United States. It started small but grew into a “jungle” engendering a welter of useful (and sometimes bizarre) ideas and innovations.

On the other hand, if we tried to create a huge snail, we would inevitably fail. The trick is to create the platform that allows the snail to evolve naturally. Let’s focus on building jungles, not snails.