Featured

This week’s featured posts.

This week’s featured posts.

Rock climbing, biking, or violent crime?

My resting heart rate is 56 beats per minute. I’ve always interpreted that as a sign of good health. It may also mean that I’m a natural born killer.

That’s one of the conclusions that Adrian Raine might like you to draw from his new book, The Anatomy of Violence: The Biological Roots of Crime. Raine’s work is essentially a continuation of E.O. Wilson’s research on sociobiology. Wilson linked evolutionary and genetic influences to human behavior and, especially, to our reproductive habits, urges, and processes.

Raine takes sociobiology a step farther. If our genes can influence our reproductive behaviors, could they not also influence violent and criminal behavior? Are criminals different than non-criminals in some biological way? If so, can we use biology to predict who will commit crimes? Then what?

Let’s take low heart rate, for example. Raine reports evidence that a significant number (much higher than chance) of antisocial criminals have lower than average resting heart rates. Further, the condition points toward violent crime and not to other forms of behavior. It’s not only a predictor; it’s also a specific predictor.

Why would low heart rate point to violent crime? Raine offers three theories. First, there’s the fearlessness theory — “A low heart rate is thought to reflect a lack of fear.” Second is the low empathy theory – “Children with low heart rates are less empathic than children with high heart rates.” Third is the stimulation-seeking theory – low heart rate is associated with low arousal and “…those who display antisocial behavior seek stimulation to increase their arousal levels…”

I’m going with stimulation-seeking theory. Perhaps that’s why I took up rock climbing at the tender age of 18. I just needed some stimulation.

So, what might we have predicted about my behavior when I was, say, 15? It might have been this: “Travis has a low heart rate. Therefore, we can safely predict that he will either become a rock climber or a psychopathic serial killer.” Hmm… now what?

Let’s say I do commit a crime. Does my low heart rate absolve me of responsibility? Should a jury put me in jail or simply require that I take stimulants to boost my heart rate? Or should the government require me to take such stimulants before I commit a crime, just to be on the safe side?

It’s a debate we need to have and Raine begins to frame it up. Unfortunately, he’s rather sloppy. For instance, he seems to make a fundamental error in explaining correlation and variability.

Raine, with fellow researcher Laura Baker, studied whether violent behavior can be inherited. They used “sophisticated statistical techniques” (multivariate analysis) to estimate the heritability of such behavior. Raine writes that he and Baker found, “Heritabilities that ranged from .40 to .50. That means that 40 to 50 percent of the variability among us in antisocial behavior is explained by genetics.”

Multivariate analysis, however, sorts out correlations, not variability. The degree of variability is not the correlation itself but rather the square of the correlation. With a correlation of .40, for instance, the square is .16. If X and Y have a correlation of .40, then 16% of the variability in Y is explained by X. Thus, Raine and Baker can explain between 16% and 25% of the variability in antisocial behavior through inheritance. That’s an important finding but not nearly as strong as Raine claims. It’s a fundamental mistake and weakens the argument considerably.

Elsewhere, Raine writes that Ted Bundy killed approximately 35 women. A few pages later, Bundy’s victims total more than 100. Raine informs us that his wife, sister, and cousin are all nurses. Therefore, he picks a nurse, “Jolly” Jane Topppan, to illustrate the “breakdown in the moral brain”. I don’t understand why Jolly Jane illustrates such a breakdown better than, say, Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber (who, by the way, has a resting heart beat of 54).

I find this irksome because I generally agree with Raine’s claims. Biology does influence our behavior. Through poor editing and sloppy statistics, however, he undermines his own argument. Raine’s book is a good start but I hope a stronger, more tightly reasoned book comes along soon. In the meantime, I need some stimulation. I think I’ll take up nude skydiving.

Budget this!

Time, cost, and quality. Pick any two.

It’s a good thought to keep in mind when managing a project. You can choose to optimize two — and only two — of the three parameters. The third parameter will always go in the other direction. Let’s say you want something done in less time and at lower cost. By optimizing those two parameters, you’ve sub-optimized the third – quality will suffer. If you want high quality at low cost, well… it’s going to take a long time. Pick any two.

Interestingly, we only measure two of the three parameters. We have armies of accountants to keep track of how we spend our money. We have quality control experts to measure quality. We have no one who keeps track of how we spend our time. Are we spending our time wisely? Are we allocating our time based on strategic objectives? Who knows? We treat time as an infinite resource.

Though we treat money and assets and goodwill as corporate resources, we treat time as a personal resource. How you spend your time is pretty much up to you. This higher you rise in the ranks, the more you control your own time.

And that’s a practice that needs to change according to “Making Time Management the Organization’s Priority,” a recent article from the McKinsey Quarterly. As the article notes, “Time management isn’t just a personal-productivity issue … [it’s] an organizational issue whose root causes are deeply embedded in corporate structures and cultures.”

How can you change the “time culture” in your organization? The McKinsey article provides six suggestions. To save time, I’ll cover three today and three more in an upcoming post.

Create a time leadership budget – this may sound obvious but far too few organizations actually do it. When you create a proposal for a new project, you always include a cost budget. How about a leadership time budget? You can think of leadership time as a general corporate resource – just like money. Let’s say you have ten executives working on new projects. Assuming, that each works 2,000 hours per year, that’s an overall “budget” of 20,000 hours. If you add a new project, how much leadership time will it take? What will you take away to make the budget balance?

Think about time when introducing organizational change – organizational change takes enormous resources, much more than we typically estimate. That includes time. Yet we often ask managers to change things while also doing their “day” jobs. Establishing a leadership time budget can help here. So can managerial restructuring. My rule of thumb — call it the Travis rule — is that more managers mean more meetings. Reducing the number of managers can (within reason) reduce the number of hours spent in meetings and re-balance the time leadership budget.

Measure and manage time – ask your leaders to keep track of their time by keeping a simple diary. As McKinsey points out, “Executive are usually surprised to see the output from time analysis exercises, for it generally reveals how little of their activity is aligned with the company’s stated priorities.” As the old saying goes, if you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it.

Let’s exercise a little time budgeting here. Most people read at about 200 words per minute. This article is about 600 words long. So you’ve been reading for three minutes. Time to get back to work.

Would you prefer to: 1) work the same number of hours and earn more money, or; 2) work fewer hours and earn the same money? According to Geert and Gert Jan Hofstede this question can help us ascertain whether a culture is “feminine” or “masculine”.

Would you prefer to: 1) work the same number of hours and earn more money, or; 2) work fewer hours and earn the same money? According to Geert and Gert Jan Hofstede this question can help us ascertain whether a culture is “feminine” or “masculine”.

The Hofstedes are academic researchers who study the influence of national cultures on organizational behavior. The Hofstedes write that there are five basic dimensions of culture: 1) power distance — the degree of equality/inequality in a culture; 2) individualist/collectivist continuum; 3) masculine/feminine; 4) Uncertainty avoidance — the degree to which we believe that what’s different is dangerous; 5) short-term/long-term orientation. I’ve written about the first two previously (here and here). Today, let’s talk about masculine/feminine. I’ll cover the other two in the near future.

According to the Hofstedes, the masculine/feminine dimension has mainly to do with the degree of differentiation between gender roles. In “masculine” cultures, “…gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.” In “feminine” cultures, “… gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.”

As with their other dimensions, the Hofstedes develop a scale (MAS) and rank order 74 countries. The five most “masculine” countries are Slovakia (MAS = 110), Japan (95), Hungary (88), Austria (79), and Venezuela (73). The most “feminine” countries are Sweden (MAS = 5), Norway (8), Netherlands (14), Denmark (16), Slovenia (19). The United States has an MAS score of 62, making it the 19th most “masculine” country on the list.

The masculine/feminine dimension is the only one of the five dimensions that is not correlated to national wealth. In general, wealthier nations tend to have smaller power distance (more egalitarian), lean toward individualism, are more comfortable with uncertainty, and have a long-term orientation. The masculine/feminine dimension, on the other hand, has no relationship to wealth. We see rich and poor masculine cultures and rich and poor feminine cultures in approximately equal proportions.

In very general terms, masculine cultures are about ego, feminine culture are about relationships. In masculine cultures, status purchases (expensive watches, jewelry) are common and people buy more nonfiction books. In feminine cultures, people buy more products for the home, invest more in do-it-yourself projects, and buy more fiction. In masculine societies, failure at school is a catastrophe and may lead to suicide. In feminine societies, school failure is a relatively minor incident. In masculine societies, competitive sports tend to be part of a school’s curriculum; in feminine societies, they are extracurricular.

In the workplace, the masculine/feminine continuum produces important differences in work content and management styles. In masculine cultures, we might hear people say, “I live to work”. In feminine cultures, we’re more likely to hear, “I work to live”. Answering the opening question (above), masculine societies tend to prefer more salary for the same hours; feminine societies prefer the same salary for fewer hours.

Job enrichment also varies by culture. In masculine societies, enrichment largely means more opportunities for advancement, recognition, and challenge. In feminine societies, enrichment is more about relationship building and mutual support. In feminine cultures, small is beautiful. In masculine cultures, bigger is better. In feminine societies, careers are optional for both genders. In masculine societies, careers are mandatory for men, optional for women.

You can find the Hofstede’s book here.

A spammer? Moi?

I run my little consulting business out of an expansive office in our basement. The business is going reasonably well — I have clients in both Sweden and the United States. Still, I have some slack time every now and again. I need to do some marketing to build the business.

So far, my marketing consists of this website, some social media, and some nice t-shirts. (If you want a t-shirt, send me your size). I maintain a Twitter feed, a Facebook page, and a Linked In page. I considered advertising on the Super Bowl but decided that the demographics were wrong. Then I noticed that my Facebook views had dropped dramatically. Even people who had “liked” my page weren’t seeing my posts. Facebook had apparently changed its algorithms to “suppress” views of pages that don’t advertise with the company. (For more on this, see Nick Bilton’s post in the New York Times).

So I decided to advertise on Facebook. I think I create some pretty good posts, so I simply paid Facebook to advertise them for me. I made a modest investment — $5 on some days and $10 on days when I addressed a really hot topic. The results were weird to say the least.

First the results were completely unpredictable. On the day before I bought my first ad, 29 people saw my post — though I have well over 500 friends on Facebook. With my first ad — a $5 day — 7,055 people saw my post and I got four “likes”. Here’s what happened on subsequent days:

I had asked Facebook to show my ads to people over 25 years of age who said that they enjoy reading. I didn’t change my criteria throughout the ten-day trial but I had no idea what to expect from day to day.

Then I started getting nastygrams (some very nasty) from other Facebook users. To advertise my work, Facebook simply takes one of my posts and inserts it into other users’ news feeds. A number of users, who don’t know me from Adam, took strenuous exception to this, posted obscene messages in my news feed, and reported me for spamming. I corresponded with one such user who asked me never to spam him again. I pointed out that I had bought an ad without the intention of spamming anybody. He considered it spam and had asked Facebook to “adjust their algorithm” to punish me as a spammer.

I wondered if Facebook would actually charge me for an ad and then downgrade my algorithm for spamming. That takes some chutzpah. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find out if this actually occurs. Frankly, I just don’t know whom to ask. Despite its name, Facebook is a rather faceless organization.

So, I’ve given up my Facebook ad campaign. I’m tired of the obscene responses. And, like the Super Bowl, I wasn’t reaching the right demographic. I did get more views and more “likes” but, after reading the profiles of those who “liked” me, I just don’t think any of them are going to buy my business-to-business consulting services. So, I’m looking for other ways to advertise my business. In the meantime, I still have some nice t-shirts.

Do you think that personal success results mainly from your own hard work or is it due to forces beyond your control? If you’re like 77% of Americans, you believe that success comes from hard work and personal responsibility. That shared belief cuts across all classes. It doesn’t really matter if you’re rich or poor, black or white, Republican or Democrat. No matter how you segment the American population, a majority of most every segment believes that hard work is the key to success.

Do you think that personal success results mainly from your own hard work or is it due to forces beyond your control? If you’re like 77% of Americans, you believe that success comes from hard work and personal responsibility. That shared belief cuts across all classes. It doesn’t really matter if you’re rich or poor, black or white, Republican or Democrat. No matter how you segment the American population, a majority of most every segment believes that hard work is the key to success.

That’s what known as a social contract. We may disagree on lots of hot button issues — gun control, gay marriage, abortion, deficits, etc. — but we fundamentally agree on how to be successful. We may think of ourselves as a fractured body politic but, on some very significant issues, we’re as close to unanimous as a country can be.

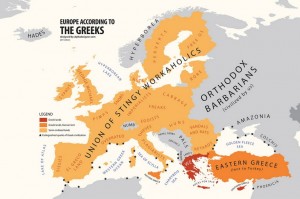

As Lexington points out in a recent column, that’s an important point to keep in mind. It’s also an important difference between America and Europe. When Pew Research asked the same question across Europe, they found a distinct north/south split. Northern Europeans — especially Britons and Germans — agreed that hard work is the key to success. Southern Europeans — especially French, Greeks, and Italians were more fatalistic — success is not because of you but because of the system. In other words, it’s undeserved. By extension, it should be shared with others.

In America, we look to Europe for both positive and negative examples. They’re sort of like us and, therefore, we should be able to learn from their experience. We can debate the merits of the euro or of austerity or of massive bailouts. But Lexington suggests that we’re missing the point. Europeans have fundamentally different world views and, as a result, they just plain don’t like each other. Lexington writes that “…America should fear the spread of the crudest poison paralysing Europe: mutual dislike between citizens.”

It seems so obvious. If we continually demonize each other, then the social contract begins to fray. But that’s exactly what we’re doing. We’re behaving more and more like Europeans. As Lexington puts it, Americans are developing an “ill-concealed contempt for an undeserving other: the feckless poor, the immoral rich …” and concludes: “Mutual dislike is the dirty secret that best explains European paralysis. American politicians have no business stoking it in their far more ambitious union.”

Let’s remember what we do agree on in America. Let’s not balkanize ourselves into another Europe. A little mutual respect would go a long way right about now.