Featured

This week’s featured posts.

This week’s featured posts.

Over the past few days, we’ve talked about redundancy and repetition. Redundancy works if you need to make sure that a message sinks in fully. Ad agencies suggest that you need to repeat an advertisement to the same audience at least six times just to make sure that it’s noticed. (And, note that “noticed” is not the same as “understood”). Yet we also learned in information science that the more frequently a signal is repeated, the less information it carries. So redundancy works best when you can vary the signal while keeping the message the same. Volvo has done exactly that as they’ve built their brand. Volvo’s message is always “safety” but they deliver the message in many different ways.

What if a person keeps repeating himself? It could mean that he’s crazy. More likely, he thinks he hasn’t been heard. If he thinks you haven’t noticed and understood his message, he’ll continue to repeat himself — even to the point of being self-defeating. There’s a simple solution — just feed back what you’ve heard. You may have to do it more than once but, sooner or later, the person will acknowledge that he’s been heard — usually by nodding his head. Once you’ve established that the message was properly received, you can move on to new topics. Take a look at the video to practice the technique.

When I lived in Stockholm, I was responsible for customers throughout Scandinavia. One of my favorite customers was Dale of Norway, the creators of richly patterned, thick wool sweaters. The sweaters are very popular with winter sport enthusiasts in my home state of Colorado. They’re stylish and they’re practical … and therein lies a tale.

I visited Dale of Norway’s headquarters and met their CEO. The company is located in a picturesque little town called Dale. (We call it Dale as in Chip and Dale but the Norwegians pronounce it Darla). When I met the CEO I mentioned that I was from Colorado and that my wife and I were both customers. The conversation went something like this:

CEO: “Let me guess. You have one sweater and your wife has three.”

Me (surprised): “Yes. How did you know?”

CEO: “Women see our sweaters as fashion statements and they’re willing to buy more than one. Men see them as a high quality product that will last a life time. If it will last a life time, why would you ever buy more than one?”

Me: “I wish I understood my customers as well as you understand yours.”

There are a couple of lessons here. First, sometimes a satisfied customer is just that: satisfied. I was a very satisfied Dale of Norway customer. If you did a customer satisfaction survey, I would be right at the top. But I was generating exactly zero revenue for the company.

One of Dale of Norway’s challenges was to overcome the satisfied customer curse. They needed to give me (and even my wife) more reasons to buy. To complement their heavy weight sweaters, they introduced two new product lines — mid-weight sweaters and lighter weight accessories. I’m now the proud owner of a mid-weight sweater and some long underwear. I’m still satisfied but, more importantly, I’ve generated new revenues for Dale of Norway.

The second lesson: different people buy for different reasons. Don’t ever assume that what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. To the maximum extent possible, live with your customers. When you see the world through their eyes, you’ll find that different groups see your product differently. There’s nothing surprising in that — it’s just segment marketing. Unless you understand how each segment thinks, you’ll never communicate effectively with them. One message does not fit all.

The third lesson? Dale of Norway makes great sweaters, gloves, mittens, and scarves. So get out there and buy one … or two … or three. You can find them here.

I’ve noticed a pattern among my clients. Many of them are small software companies with good ideas that are growing rapidly. When they first call me, they have approximately 150 employees. I’ve often wondered, what is it that triggers a problem — and a call to an outsider — at 150 employees?

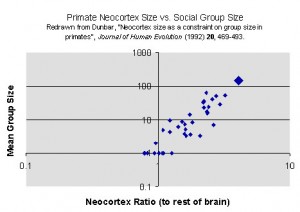

Then I discovered Dunbar’s number and the pattern started to make sense. Robin Dunbar, a British anthropologist, is an expert on the social lives of monkeys. (Wouldn’t you love to have a job like that?) Dunbar made an interesting observation: Monkeys with small brains have small social circles. Monkeys with larger brains have larger social circles. Actually, it’s not total brain size — it’s the size of the neocortex, the area of the brain where we do our abstract reasoning. In Dunbar’s charts, you’ll find a distinct up-and-to-the-right relationship between the size of the neocortex (relative to the rest of the brain) and the size of the social group.

So, you might wonder, how does this affect the lives of large-brained primates known as humans? How big is our “natural” social group? Funny you should ask. Dunbar frames the question this way: what’s the largest number of people in which it’s possible for everyone to know each other and also to know how everyone relates to everyone else? The answer is slippery but it seems to be around 150 people (plus or minus, oh, say 30).

How many for humans?

If you search the topic on the web, you’ll find a number of observers arguing for a higher number. (I didn’t find any arguing for a lower number). On the other hand, you’ll also find observers who claim that 150 occurs frequently and “naturally” in traditional societies. Apparently, the Roman Legions were divided into companies of 150 men. Church parishes in 18th century England contained 150 people. If your parish grew bigger, the bishop would campaign for an additional church.

How does Dunbar’s number affect organizations? Generally speaking, a smaller organization can be fairly loosey-goosey. We all know each other and we all know how we relate to each other. We don’t need a lot of structure. Above 150, however, organizations start to get more bureaucratic. According to Wikipedia, “…analysts assert that organizations with populations of people larger than Dunbar’s number … generally require more restrictive rules, laws, and enforced norms, to maintain a stable, cohesive group.”

Maybe this is why companies call me when they reach about 150 employees. They’re growing up and they’re feeling the growing pains. It’s not as simple as it used to be. In fact, it’s getting rather complicated. I hope they keep calling me. I’m becoming a bit of a specialist.

You can find Dunbar’s original article here.

An employee has generated a good idea. Your company’s Idea First Responders have accepted the idea, stabilized it, and started to transport it to the next phase of your innovation process. And where should they take it? One good place is the Free Port.

Free Ports of old accepted ships of all nations and gave them safe harbor. That’s a good model for harboring and developing new business ideas. An Idea Free Port may be as simple as a department manager’s “good idea” file. Or it may be a prestigious, cross-departmental committee tasked with the development and implementation of good ideas. Your Free Port should adopt rules that conform to your company culture. Here are some guidelines:

Free Ports can get bogged down in bureaucratic red tape. To avoid this, keep meetings brief and keep measurements rough. (New ideas are notoriously hard to measure. Don’t overdo it.) Also, keep the CEO involved. She can resolve disputes quickly and make the many judgment calls that need to be made. Her presence will also remind people of how important the Free Port really is.

Long, long ago when I was a graduate student, I was working late in the computer lab trying to solve a complex programming problem.

Though I had written most of the code I needed, I just couldn’t figure out how to code the crux of the problem. After several hours of hit-and-miss programming, I gave up and walked home.

During my 15-minute walk, the answer popped into my head. I made two observations: 1) I had a good idea while I was walking; 2) I’m not a very good programmer — the problem wasn’t so terribly difficult.

The second idea helped me re-plan my career. Maybe I shouldn’t be a programmer after all. The first idea helped me be successful in my career.

I don’t claim to be a very creative thinker. But I do have a good idea every now and again. When I do, I try to note and remember my circumstances. I figure that there’s something about the environment that promotes creative thinking. Conversely, there are some environments that seem to inhibit — perhaps prohibit — creative thinking. To stimulate my creative processes, I need to insert myself into more of the former environments and fewer of the latter.

Here’s what I’ve found. I have a lot of my good ideas — perhaps a majority — when I’m walking. I’m a visual thinker and there’s a lot to see when I’m out for a walk. It’s stimulating. Yet it doesn’t require so much attention that I can’t process things in the back of my mind. If I’m walking with my wife, she often points out things that I might have missed. Then I can ask myself, “why did I see X but not Y?” That can stimulate interesting thoughts as well.

Other activities that seem to stimulate creativity (for me, at least) include riding a bike, light exercise at the gym, flying in an airplane, riding a train, taking a shower, and cooking oatmeal. It’s an odd combination. The common thread seems to be that I’m doing something that takes part of my attention but not all of it.

Here are some places where I never have good ideas: airports, commuting in heavy traffic, watching TV, and sitting in business meetings. It’s ironic that good ideas don’t come to me in business meetings. Basically, I’m trying to keep up with the conversation. If I’m a good listener, then I’m paying attention to other people rather than processing interesting thoughts myself.

I find brainstorming sessions useful though I rarely have a good idea when I’m in one. It’s like thinking of a good joke. If you ask me to tell a good joke, my mind goes blank. If my mind is wandering, however, I can think of a dozen jokes. It’s the same in brainstorming sessions. I try to follow the conversation and the various social interactions. That means I’m not processing stray, random, and perhaps interesting thoughts. For me, brainstorming sessions are useful for enhancing group communication and building trust. That creates the conditions for creating ideas.

I’m not at all sure that my “creative” activities will work for you. So here’s a suggestion: keep an idea log. Don’t just jot down the idea. Jot down where you were and what you were doing when the idea occurred to you. Sooner or later, you’ll see a pattern. Then you can create more “creative” experiences. In the meantime, I’m going for a walk.