The Art of Bouncing Back

Never, ever, ever, ever, ever give up.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. We’ve all heard the phrase and we know it’s true. It’s better to prevent something bad (cancer, terrorism) than it is to try to cure it after the fact.

But life is full of risks and we can’t prevent all of them. What happens when you can’t prevent something bad from happening? How well do you bounce back? It’s a question of resilience – our ability to manage stress rather than allowing it to manage us.

We aren’t resilient by nature; it’s not an inborn trait. We learn (or don’t learn) resilience through experience and practice. I’ve been reading up on resilience in a number of different articles (click here, here, here, and here). Here are some tips.

Cognitive reappraisal – we all do dumb things or fail at certain endeavors. Failures can leave lasting scars. We think of a dumb thing we did – even long, long ago – and we conclude that we’re just not up to snuff. The next time we do something dumb, it just shows how mediocre we are. We don’t bounce back effectively because, …. well, we’re just not good enough.

But we can also revisit and reinterpret our failures. For instance, I once wanted to be a baseball player. I was a good fielder but I couldn’t hit well. Ultimately, I failed and for a while I was crushed. Looking back on it, however, I realize how lucky I was to learn the lesson early. I refocused on my studies and did reasonably well. More recently, I’ve reappraised my baseball failure. Now when I fail at something, I think, “Well, maybe it’s like baseball….” That helps me bounce back more quickly.

Make connections – all the resilience research I’ve read says it’s easier to be resilient when you have a close network of friends and family. When I’m having a bad day, I sometimes just want to withdraw. But I find that I bounce back better when I’m around other people. Build your network early; you’ll need it sooner or later.

Think positively – it may sound trite but it works. If you think of yourself positively, then a failure is the exception, not the rule. Even a very stressful event isn’t really about you. Your self-image provides a protective layer. A bad thing happened but that doesn’t make you a bad person. If you still perceive yourself positively, it’s easier to bounce back. A major blow can even provide the motivation (“I’ll show them”) to bounce back strongly.

I’ve picked up some other tips about resiliency and I’ll cover them in future posts. What I’m really looking for, however, is the link between resiliency and creativity. I’ve noticed that some of my more creative moments come soon after a setback, a failure, or just a very bad day. I think that resiliency can contribute to creativity but I don’t know quite how. If you see a link between the two, let me know your thoughts.

Extrinsic, Intrinsic Creativity

I love my work.

When I think about motivating people, I often think about extrinsic factors. What can I do to provide incentives to guide another person’s behavior? This usually involves rewards of one type or another – perhaps money or praise or recognition.

If we want to stimulate creativity, however, Teresa Amabile argues that we need to pay more attention to intrinsic motivation. As Amabile writes, “When people are intrinsically motivated, they engage in their work for the challenge and enjoyment of it. The work itself is motivating.” (Amabile’s article, “How to Kill Creativity” is a classic).

So how do you improve intrinsic motivation? Basically, it’s about leadership, culture, and values. I used to think that intrinsic motivation – being internal – was not subject to external factors. But Amabile’s research leads her to conclude that, “…intrinsic motivation can be increased considerably by even subtle changes in an organization’s environment.” Amabile outlines six factors to consider.

Challenge – this is management’s ability to match the right job to the right person. The ideal job stretches a person but not to the breaking point. To do this successfully, managers need to understand their employees quite well.

Freedom – there are many ways to develop a road map of where we’re going. Whether employees are included in the process is not crucial to creativity. What is crucial is giving employees a lot of latitude in determining how they’re going to get there.

Resources – the big ones are time and money. Setting unrealistic deadlines can derail creativity. (For more about time as a resource, click here). Money can also affect creativity. As Amabile points out, keeping resources too tight, “…pushes people to channel their creativity into finding additional resources, not in actually developing new products or services.” On the other hand, beyond a certain “threshold of sufficiency”, more money doesn’t help.

Work group features – designing a diverse team is critical. If everyone on the team thinks alike, you won’t get creativity. If people from different disciplines collaborate, they may just mash up ideas in very innovative ways. You need diversity, but you also need someone who can help diverse people collaborate – not always an easy task. As Amabile points out, homogenous teams often have high morale but low creativity. Managing morale on a diverse team may be more difficult, but the dividend is creativity.

Supervisory encouragement – we all need encouragement from time to time even if we’re intrinsically motivated by our work. A crucial factor is what happens to a new idea when it’s first proposed. Is it a positive experience? Or is the proposer raked over the coals? Do staff members show how “smart” they are by being critical? Does the idea become a political football? (The concept of Innovation Free Ports addresses this).

Organizational support – individual supervisors can be encouraging, but the entire organization needs to support creativity. This is all about leadership, culture, and values. For instance, information sharing is critical to creativity. If your company culture creates a competitive internal environment where information is hoarded rather than shared, you won’t get creativity. If your culture emphasizes “go along to get along”, you won’t get the diverse ideas that stimulate discussion and creativity (and discord, on occasion).

As you’ve probably guessed, it’s all about people. Take the time to understand people – and their desires and motivations – and you’ll be well rewarded.

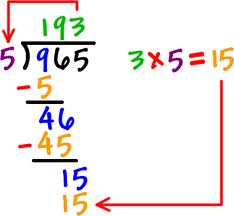

The Beauty of Long Division

Remember long division? You have a big number and want to divide it by a small number. You draw a little house, put the big number in it, and the small number outside it. Then you start guessing. Roughly how many times will the small number go into the large number?

Remember long division? You have a big number and want to divide it by a small number. You draw a little house, put the big number in it, and the small number outside it. Then you start guessing. Roughly how many times will the small number go into the large number?

You’ll be wrong the first time but it doesn’t matter. You start refining. If your first guess is close, you can refine it in a few steps. If your first guess is way off, you’ll need to take more refining steps. Either way, the method works. In fact, it’s pretty much foolproof. Even fourth graders can do it.

I got this example from an elegant little book I’m reading called Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking by the philosopher, Daniel Dennett. The general idea is that thinkers, like blacksmiths, have to make their own tools. We’ve used some tools for millennia; others are of more recent vintage.

As long division illustrates, one tool is approximation. (Technically, it’s known as heuristics). In the real world, we don’t always have to be precise. We start with a guess and then refine it. The important thing is to make the guess. That’s the ante for getting into the game.

It’s surprising how often this works. In fact, now that I’m thinking about it, I realize that I make guesses all the time. Guessing is certainly a good management tool. In the hurly burly of commerce, it’s not always clear precisely what’s happening. It usually takes accountants four to six weeks to figure out precisely what happened in a given quarter. In the meantime, it’s useful for day-to-day managers to make educated guesses. Learning to make such guesses is a critical skill.

I realized that I also apply this to my writing. I sometimes get writer’s block. I know the argument I want to make but I don’t know how to frame it. I can’t get started. When that happens, I make an effort to just write something, even if it’s sloppy and poorly phrased. Once I have something written down, I can then shift gears. I’m no longer writing; I’m editing. Somehow, that seems much easier.

As you think about thinking, think about guessing. In many cases, you’re more likely to get to a clear thought through approximation than through a brilliant flash of insight.

Are Creative People Weird?

Can’t you just focus?

I’ve always been proud of my ability to focus. In many situations, I can quickly distinguish between what’s relevant and what’s not. I can then block out irrelevant information and focus, for long periods of time, on what’s important. It’s a handy skill for a manager.

Like most skills, however, it comes at a price. First, it makes me a bit of an absent-minded professor. I may lose track of “irrelevant” details like anniversaries and birthdays. However, the more costly price may be a loss of creativity.

When I focus intently on something, I’m doing what a neuroscientist would call “cognitive inhibition.” In simple terms, I’m blocking out. I’m inhibiting information from entering my consciousness. I block out a lot of irrelevant stuff but I may also block out information that could lead to a creative solution.

We often think of creative people as being uninhibited. We use the term to describe their behavior rather than their thinking processes. They may dress unfashionably, behave eccentrically, write strident manifestos, and generally seem at odds with the mainstream culture. This is not a new phenomenon; Plato commented about the odd behavior of poets and playwrights.

We use the term uninhibited to describe behavior, but we should also apply it to thinking processes. In fact, a neuroscientist would call it “cognitive disinhibition”. Essentially, it means that we loosen the filters and allow a variety of thoughts to float to the surface. Fewer thoughts are inhibited or blocked out. Some people seem naturally to have fewer filters.

According to Shelley Carson in her article “The Unleashed Mind”, cognitive disinhibition is the basis of both eccentric behavior and of creativity. Carson defines cognitive disinhibiton as “…the failure to ignore information that is irrelevant to current goals or to survival.” Sometimes, this simply leads to bizarre thoughts and psychosis. For people with high IQs and large working memories, on the other hand, it can lead to creative eccentricity. Carson proposes a “shared vulnerability model” that underlies creativity, eccentricity, and high functioning “normal” performance.

The way we talk about creativity gives a clue to Carson’s model. When we have an “aha” moment, we often describe it as a “breakthrough”. We have literally broken through something – in this case, our cognitive inhibition. If we can lower the resistance to a breakthrough – by reducing our inhibitions – we can become more creative … and, perhaps, more eccentric.

Some moths ago, I wrote a brief article about sleep and creativity. We’re more creative when we’re sleepy. Carson’s model explains why: when we’re sleepy our cognitive inhibitions are lower. I’ve also written about caffeine and creativity. Caffeine keeps us focused. By doing so, it also reduces our creativity.

As it happens, I’m a huge consumer of caffeine. Perhaps that’s why I can focus intently on relevant information. Maybe it’s time to take a caffeine break to see if I can be more creative … and maybe a bit more eccentric.

Thinking and Health

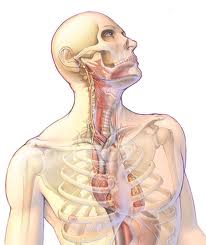

Does the mind influence the body or vice-versa? It seems that it happens both ways and the vagus nerve plays a key role in keeping you both happy and healthy (and creative).

Does the mind influence the body or vice-versa? It seems that it happens both ways and the vagus nerve plays a key role in keeping you both happy and healthy (and creative).

Also known as the tenth cranial nerve, the vagus nerve links the brain with the lungs, digestive system, and heart. Among many other things, the vagus nerve sends the signals that help you calm down after you’ve been startled or frightened. It helps you return to a “normal” state. A healthy vagus nerve promotes resilience — the ability to recover from stress. (The vagus nerve is not in the spinal cord, meaning that people with spinal cord injuries can still sense much of their system).

The vagus also helps control your heartbeat. To use oxygen efficiently, your heart should beat a bit faster when you breathe in and a bit slower when you breathe out. The ratio of your breathing-in heartbeat to your breathing-out heartbeat is known as the vagal tone.

Physiologists have long known that a higher vagal tone is generally associated with better physical and mental health. Most researchers assumed, however, that we can’t improve our vagal tone. Some lucky people have a higher vagal tone; some unlucky people have a lower one. It’s determined by factors beyond our control.

Then Barbara Fredrickson and Bethany Kok decided to see if that was really true. Their research – published in Psychological Science – suggests that we can improve our vagal tone. By doing so, we can create a virtuous circle: improving our mental outlook can improve vagal tone which, in turn, can make it easier to improve our mental outlook. (For two non-technical articles on this research, click here and here).

In their experiment, Fredrickson and Kok randomly divided volunteers into two groups. One group was taught a form of meditation (loving kindness meditation) that engenders “feelings of goodwill”. Both groups were also asked to keep track of their positive and negative emotions.

The results were fairly straightforward: “All the volunteers … showed an increase in positive emotions and feelings of social connectedness – and the more pronounced this effect, the more their vagal tone had increased ….” Additionally, those who meditated improved their vagal tone much more than those who didn’t.

The virtuous circle seems to be associated with social connectedness, which Fredrickson refers to as a “potent wellness behavior”. The loving kindness meditation promotes a sense of social connectedness. That, in turn, improves vagal tone. That, in turn, promotes a sense of social connectedness. Bottom line: it pays to think positive thoughts about yourself and others.