As we become more energy efficient, do we use less energy?

We buy my wife, Suellen, a new car every ten years whether she needs one or not. It’s always a red Volkswagen convertible with a  manual transmission. (She’s old school). We bought the first one in 1985, another one in 1995, and the current one in 2005. She just looks cute in a red convertible.

manual transmission. (She’s old school). We bought the first one in 1985, another one in 1995, and the current one in 2005. She just looks cute in a red convertible.

What struck me about these three cars was how power was deployed. The 1985 model had roll-up windows and a manually operated roof. The ’95 had power windows and a manual roof. The ’05 has both power windows and a power roof. The 2005 model is clearly more energy efficient than the ’85 model but does it use less energy?

I didn’t know it at the time but I had struck on something called Jevons paradox (also known as the rebound effect). Named after William Stanley Jevons (pictured), a British economist in the mid-19th century, the paradox states that increasing energy efficiency leads to greater energy use. It’s basically a cost curve. Increased energy efficiency means each unit of energy costs less. As costs decline, we buy more energy — just as we do with most commodities.

The result: instead of raising and lowering the convertible’s roof with arm power, we put in a little motor to do it for us. According to Jevons, the net effect is that we use more energy rather than less.

I’ll admit that I’m a tree hugger and that I’m concerned about global warming. I also study the processes of innovation and I generally applaud innovations that result in greater energy efficiency. But the more I ponder Jevons paradox, I wonder if we’ve aimed our innovations at the wrong target. Shouldn’t we be creating innovations that help us use less energy rather than more?

(If you want to read more about Jevons paradox, The New Yorker has a terrific article here. On the other hand, Think Progress says the paradox exists in theory but not in practice. That article is here. Interesting reading).

Strategy: What Wouldn’t You Do?

In many ways, strategy is simple. Yet we often want to make it more difficult and more complicated than it really is. We want it to sound powerful and provocative. We want to inspire our employees and investors with eloquent phrases and motivational messages. But strategy, in itself, is not inspirational. You can create inspirational messages about your strategy but the strategy itself simply says, “we do this; we don’t do that”.

In many ways, strategy is simple. Yet we often want to make it more difficult and more complicated than it really is. We want it to sound powerful and provocative. We want to inspire our employees and investors with eloquent phrases and motivational messages. But strategy, in itself, is not inspirational. You can create inspirational messages about your strategy but the strategy itself simply says, “we do this; we don’t do that”.

Be sure to separate the messaging (and the inspiring) from the strategy per se. A simple way to clarify your strategy is to focus on what you don’t do. By clearly defining what you don’t do, you can save yourself a lot of time and grief. You can invest that time into doing a better job of what you do do. That’s inspirational.

Learn more in the video.

Does Money Matter (Part 2)

When our mass media evolved to reach of millions rather than thousands, social scientists created new theories. How would the media influence people’s behavior and attitudes? Sociologists started with the “hypodermic needle” model of influence — media “injected” opinions, beliefs, and attitudes into passive audiences. Recipients had no control. Once they were injected, their opinions and beliefs started to sway. The more they were injected, the more likely they were to move in the specified direction. Pundits feared that, given enough exposure to propaganda, God-fearing, freedom-loving Americans could be converted to communist atheists.

When our mass media evolved to reach of millions rather than thousands, social scientists created new theories. How would the media influence people’s behavior and attitudes? Sociologists started with the “hypodermic needle” model of influence — media “injected” opinions, beliefs, and attitudes into passive audiences. Recipients had no control. Once they were injected, their opinions and beliefs started to sway. The more they were injected, the more likely they were to move in the specified direction. Pundits feared that, given enough exposure to propaganda, God-fearing, freedom-loving Americans could be converted to communist atheists.

If the hypodermic model were accurate, money really would make a difference in presidential elections. Whichever side could run more ads and “inject” more viewers would win. Spend more money, win more elections.

Our understanding of mass media has evolved, however. We now think of it as a two-step model. First, the media influence (but don’t “inject”) opinion leaders in a given social circle. Second, the opinion leaders influence other people in the group. Perhaps fortunately, opinion leaders have only limited spheres of influence. For instance, my friends think I’m an opinion leader on computing technology. They ask my opinion. On the other hand, they never ask my opinion on gardening.

Political campaigners (and advertisers) want desperately to reach opinion leaders. It’s not easy, however, because a leader on one topic is not a leader on another. Even someone who is well informed may not be influential. I have friends who are dedicated leftists and others who are confirmed rightists. They read a lot, they seem well informed, and they’re very sure of their own opinions. But, they always offer the same pat solutions. I don’t trust either of them to influence my opinion. They’re not thinkers; they’re believers.

If politicians can’t count on their true believers to influence others voters’ opinions, what can they do? How do they target their messages? Fortunately or unfortunately, they can’t target very well. So they just carpet bomb. They’re using a hypodermic model in a two-step world. It doesn’t work. It never did. What a waste of money.

Does Money Matter? (Part 1)

In the Citizens United case in 2010, the Supreme Court effectively removed all constraints on spending for political advertising. The Supremes argued — in a 5-4 decision – that the First Amendment prohibits the government from restricting free speech or, by extension,  from spending money to speak freely. For all practical purposes, this means that corporations, unions, and just plain rich people can spend as much as they want to promote a candidate or a cause.

from spending money to speak freely. For all practical purposes, this means that corporations, unions, and just plain rich people can spend as much as they want to promote a candidate or a cause.

As a result, we’ve seen a tidal wave of money — and a few bizarre billionaires — injected into this year’s presidential campaign. My question is: does it matter?

I come from the tech world and I can think of many examples where a small, poorly funded company took on a well-entreched giant and ate not only their lunch but also their breakfast and dinner. Think of SUN Micro versus IBM. Or Google versus Microsoft. In the political world, the Arab Spring revolts in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt suggest that money (and even coercion) can’t stop a good idea once it starts spreading.

I’ve also seen many expensive promotional campaigns that yielded little or nothing. A recent example from the tech world is Nokia’s big push for the Lumia 900 smart phone. A massive promotional campaign yielded minimal sales. (Anybody remember the Lumia 900?) A well-documented example in the political world was George Bush’s big push in 2004/5 to partially privatize Social Security. Bush launched a well-funded, well-coordinated nationwide campaign and spoke on at least 65 occasions to promote the idea. The more he spoke, the less popular the idea became. (I have an article in the works on this topic).

I see a big difference between changing your mind and changing your values. (In fact, this is a major insight of classical rhetoric). I don’t think many people will change their values just because they see a 30-second commercial. An angry commercial may activate people (and that’s important) but I don’t think it will change people. In fact, an angry and cynical ad may push people in the opposite direction. I’ll discuss reasons for this in my next article.

Of course, if I were running a political campaign, I would prefer to have more money than my opponent. But money isn’t everything. For instance, I’ve worked for small companies battling against larger companies for my entire career. I wouldn’t say that all my adventures ended happily but many of them did.

So, will the massive spending in the 2012 election affect the outcome? It’s a grand experiment. One possible — perhaps probable — outcome is that we’ll get to November 7 and find the politicos saying, “Wow, we just spent a massive amount of money and it had no impact whatsoever. There must be a better way to spend our money.” If that happens, the 2016 election will be a lot more pleasant.

(Speaking of 2016, what do you think? Condoleezza versus Hillary?)

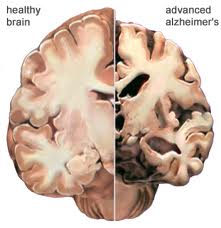

Is Alzheimer’s Type 3 Diabetes?

I normally write about topics related to strategy, innovation, branding, and communication. I just spotted an article about new research  on Alzheimer’s, however, and thought I would pass it on. (My Mom had Alzheimer’s so I’m interested). In the latest edition of New Scientist magazine, an article titled “Food For Thought” traces the connection between insulin and Alzheimer’s.

on Alzheimer’s, however, and thought I would pass it on. (My Mom had Alzheimer’s so I’m interested). In the latest edition of New Scientist magazine, an article titled “Food For Thought” traces the connection between insulin and Alzheimer’s.

We’ve known for some time that insulin plays a role in regulating sugars and fats in the body. It turns out that insulin also helps the brain manage its consumption of glucose — and the brain sucks up a lot of glucose. The “Type 3” hypothesis posits that disrupting our insulin management system (as in Type 2 diabetes) can lead to plaques that are typical of Alzheimer’s. If that’s true — and it’s certainly not proven yet — then taking steps to reduce Type 2 diabetes could help reduce future cases of dementia.

You can find the New Scientist article here. I looked up some other references as well. The Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology notes that “there is a rapid growth in the literature pointing toward insulin deficiency and insulin resistance as mediators of … neurodegeneration” and then proceeds to review the literature. The conclusion: “…these studies provide strong evidence in support of the hypothesis that AD represents a form of diabetes mellitus that selectively afflicts the brain.”

An article from Rhode Island Hospital, notes that one of its researchers, Suzanne de la Monte, M.D., “has found a link between brain insulin resistance (diabetes) and two other key mediators of neuronal injury that help Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to propagate.” An article in Emax Health suggests that “Recent research has found that insulin resistance also develops in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s, which scientists sometimes call “brain diabetes.””

So, what to do? Nothing has been proven so Im not sure that there’s anything specific to do. But the New Scientist article does suggest that regular exercise can reduce the chance of dementia by as much as 40%. So I’m going for a bike ride. Anyone want to come along?