Does Poverty Cause Poverty?

Where can I buy 13 IQ points?

Which of the following propositions is more likely correct?

- People make bad decisions and, partially as a result, become poor.

- People who are poor make bad decisions and, partially as a result, stay poor.

If you had asked me about this a week ago, I’m not sure which proposition I would have chosen. But then I read, “Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function” by Anandi Mani et. al. in the August 30th edition of Science. The editorial summary is simple and striking: “Lacking money or time can lead one to make poorer decisions, possibly because poverty imposes a cognitive load that saps attention and reduces effort.”

The authors conducted two parallel studies. One was essentially a laboratory study conducted with people in New Jersey. The other was a field study conducted among Indian sugarcane farmers.

In the New Jersey study, participants were asked to consider various financial problems that might arise in their personal lives. They were then asked to describe how they would reason through a solution. At the same time (or immediately after) they were given tests of cognitive function. The tests measured fluid intelligence – “the capacity to think logically and solve problems in novel situations…”.

The researchers correlated family income to cognitive performance. They also repeated the tests under different conditions to control for extraneous factors such as math anxiety. The general conclusion was clear: “The poor performed worse than the rich overall.”

In India, the researchers used a “natural experiment” – sugarcane farmers are poor before their annual harvest and rich afterwards. (The participants earned at least 60% of their income from sugarcane). The researchers administered cognitive function tests both pre- and post-harvest. The results were quite similar to the New Jersey tests: the farmers performed significantly better after the harvest than before. (Again, the researchers performed a number of statistical manipulations to control for extraneous variables, such as anxiety and nutrition).

What’s it all mean? The authors sum it up nicely: “Being poor means coping not just with a shortfall of money but also with a concurrent shortfall of cognitive resources. … The findings are not about poor people but about any people who find themselves poor.”

How much cognitive load does poverty impose? The authors compare their findings with other research on cognitive loads. They conclude that the deficits they measured were roughly equivalent to the cognitive deficit imposed by missing an entire night’s sleep — roughly 13 IQ points. Think about staying up all night and then trying to make complicated decisions. Your ability to make good decisions would probably suffer significantly. That’s essentially the same load that poverty imposes.

The authors conclude by discussing various policy implications. I think there are branding implications here as well. “Poor people” have a brand just like Republicans or Democrats or college professors have distinct brands. To some observers, of course, the “poor brand” is largely negative. It may just be time to take studies like these and begin re-branding what it means to be poor.

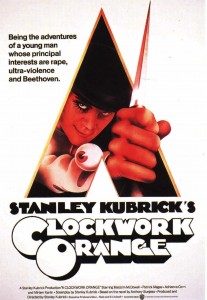

Super Sad Clockwork Orange

What would happen if we mashed up Super Sad True Love Story and A Clockwork Orange?

What would happen if we mashed up Super Sad True Love Story and A Clockwork Orange?

Published in 1962, A Clockwork Orange was set in the not-so-distant future when a gang composed of Alex and his droogs (friends) could wreak ultra-violence all about them. Super Sad True Love Story, published in 2010, was set in a “near-future dystopian New York … dominated by media and retail.” Could they be the same story?

I read A Clockwork Orange in college and re-read it last year when the 50th anniversary edition came out (with the missing last chapter). The author, Anthony Burgess, worried that a novel about the future would age badly if he used contemporary language. Just imagine reading about mods and rockers flipping you the bird while shouting, Climb it, Tarzan. It’s so 60’s

So Burgess famously invented a language – called Nadsat – that included roughly 600 words derived from Russian. Droogs are friends, a britva is a blade or razor, chepooka is nonsense, devotchka is a girl, polezny is useful, rot is a mouth, zheena is a wife, and horrorshow is cool, great, or super. It takes a little while to get used to Nadsat but, once you do, it flows easily.

I re-read A Clockwork Orange because I wanted to see how it had held up. Did Burgess’s trick work? Did Nadsat still sound futuristic? I have to say that it did; it still seemed to be a future language in an undefined but somewhat familiar landscape.

While the language held up, everything else seemed so 60’s. At one point, Alex and his droogs invade a house where an author has nearly finished typing a novel (called A Clockwork Orange). The gang seizes the typescript and shreds it in front of the author. It’s the only copy. The work is forever lost. But wait … a typewriter in the not-so-distant future? How lame is that? The language worked but the technology forecast didn’t.

Gary Shteyngart, the author of Super Sad True Love Story, may have the opposite problem, which is why a mash-up might work. I got to thinking of this when I read Shteyngart’s article, “O.K., Glass” in a recent issue of The New Yorker. The article recounts Shteyngart’s adventures as he wanders around New York wearing Google Glasses. (Shteyngart is one of the Google Glass Explorers, who are sometimes known as Glassholes).

Shteyngart uses his Glass experience to ruminate on Super Sad True Love Story. He notes, for instance that he set the novel in the near future because “…setting [it] in the present in a time of unprecedented technological and social dislocation seemed … shortsighted.”

Shteyngart is addressing the same problem as Burgess: how do you keep a novel fresh? Burgess approached it through language, Shteyngart through technology.

As Shteyngart admits, he didn’t solve the problem of predicting the far future. A lot of what he wrote has already come to pass. He writes that he feels like a “…very limited Nostradamus, the Nostradamus of two weeks from now.”

Still, I submit that Shteyngart did a better job on future technology than Burgess, while Burgess did a better job on future language. That’s why I’m proposing a mashup. Burgess died in 1993 so any mashup will have to come from Shteyngart. Plus, Shteyngart was born in Russia so Nadsat should be a snap for him. So what do you say, Gary? Would you give us a mashup of two great novels? It would be totally horrorshow.

Branding: Search, Experience, and Credence

She can influence experience goods.

As you think about branding, it’s useful to think about your goods (products or services) in one of three categories: search goods, experience goods, or credence goods.

Search goods are products whose “fitness” you can judge simply by looking at them. You can look at (and perhaps feel) an apple to tell whether it’s ripe and fit for purchase. With search goods, you can assess both the price and the value before you purchase it. Is it sturdy enough? Ripe enough? The right size? The right color? The right price?

Search goods typically are products rather than services and they’re more likely to attract price competition and substitution. If you can evaluate products simply by looking at them, you can fairly easily decide if you want to substitute one for another.

If you’re the price leader in a search good category, you’ll probably want to brand around your pricing. If you’re not the price leader, you’ll want to brand around other attributes, including secondary attributes. You may want to brand around the channel (“convenient, easy-to-find”) or the source (“a manufacturer you can trust”), longevity (“since 1916”) or geography (“Made in Boulder by Boulderians”). Packaging is also an important element in branding a search good. You want the packaging to stand out during the search.

Experience goods need to be experienced to understand how well they fit your needs. A bottle of wine is a good example – you can’t tell how good it is just by looking at it. You can identify the price but not the value. With an experience good — much more than a search good — you may assume that the price indicates the value.

You can only ascertain the value by consuming (experiencing) the product which, of course, happens well after the purchase decision. For this reason, experience goods typically have less price competition and elasticity. Indeed, a low price may be a subtle signal that there is something wrong with the product or service.

Branding an experience good often depends on reputation and word-of-mouth. People who have already consumed the product can provide useful testimony to those who are considering the purchase. This only works, of course, if the previous consumers are credible. Longevity may also play a role as potential consumers may assume that a well-established, long-lived brand offers more value than an upstart.

With credence goods, you can’t judge the value even after consuming the product or service. What’s the real value of your college degree? How successful was your hip surgery? Was it worth the price? Would it have been more successful if performed by another surgeon?

There’s no basis for comparison with credence goods. In some ways, they’re faith-based products. You need to trust your supplier. As The Economist points out, the more credulous you are, the more likely you are to be overtreated or overcharged.

In branding a credence good, previous consumers can be important but only up to a point. They can’t accurately judge value either. Let’s say a patient had the same surgery you’re considering and says he had good results with Dr. X. But how would he know if he might have had better results with Dr. Y? There’s a limit to the witness’s credibility.

For this reason, marketers of credence goods often add third-party ratings agencies (or government institutes) into their branding mix. If a neutral board of evaluators gives Dr. X a grade of 95% and Dr. Y a grade of only 94%, that’s a powerful brand differentiator for Dr. X. Note that this is true even if the differences (95% versus 94%) are small or if the rating scale doesn’t really measure what the consumer thinks it does. Most consumers rarely investigate the inner workings of third-party evaluations. A wise consumer evaluates the evaluator.

(I adapted this from Kevin Lane Keller’s excellent textbook, Strategic Brand Management).

Branding Versus Marketing

Consistent, Differentiable, Fits the Space Available

I teach a course on branding so I’m often asked to define the difference between branding and marketing. I usually have a fairly long-winded answer and I’ve noticed that the person who asked the question often leaves the conversation with a puzzled look.

Since I’m about to teach the course again, I thought I would do a web search to find a pithier answer. I wanted a simple mantra to cut through the clutter. Unfortunately, the search only added to the confusion.

Many of the sources I consulted confused marketing with selling. I’ve always thought that there were at least two parts to marketing:

- Understanding market dynamics, identifying underserved segments within markets, and developing products or services that people or companies in those segments will want to buy.

- Once you have the product/service offering, effectively communicating its benefits (of the “whole product” not just what’s in the box) to the target market to make it an appealing purchase.

I’ve always thought of marketing as a “pull” operation while sales is a “push” process. With effective marketing, you create products that people want and pull them in. Here’s how Theodore Levitt put it in his classic article, “Marketing Myopia”:

Selling focuses on the needs of the seller, marketing on the needs of the buyer. Selling is preoccupied with the seller’s need to convert the product into cash, marketing with the idea of satisfying the needs of the customer by means of the product and the whole cluster of things associated with creating, delivering, and, finally, consuming it.

All too often, the sources I found on the web (for instance, here and here and here) focused on the “second half” of marketing. They effectively define marketing as an adjunct to sales, perhaps even a support service to sales. In my humble opinion, that’s far too narrow a definition of marketing.

So, if marketing is about identifying customer needs and satisfying them, what is branding about? It’s the process of planting a consistent, compelling, and differentiable image in the customer’s mind. You want to occupy a position in the customer’s brain. The customer’s brain is probably pretty full already so she’s not going to give you much room for your position. You need to keep it simple and consistent.

This definition is essentially the customer-based brand equity (CBBE) model pioneered by Kevin Lane Keller at Dartmouth. In short, CBBE suggests that it doesn’t matter what the brand owner thinks, it only matters what the customer thinks. The value of the brand lies in the customer’s mind. The process of branding is putting appealing, differentiable images into the customer’s mind that will fit the (small) space available.

Is there a simple, pithy way to summarize all this? Here’s the best I can do. Marketing is the process of developing products that people actually want to buy and communicating the whole product benefits. Branding is the process of putting an idea in someone else’s head. Marketing is what you do. Branding is what you are.

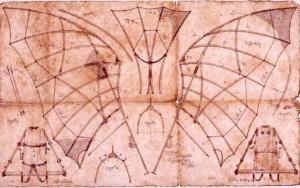

Was Leonardo Da Vinci Innovative?

Let’s tweak it, Leo.

We all know that Leonardo Da Vinci was a genius. But was he innovative?

The question draws a distinction between invention and innovation and between creativity and construction. As Wikipedia puts it, “[Da Vinci] conceptualized a helicopter, a tank, concentrated solar power, an adding machine, and the double hull, also outlining a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics. Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were even feasible during his lifetime….”

In other words, Leonardo had great ideas but many of them were never implemented. So, were they innovations?

That leads to another question: why did Britain lead the way in the Industrial Revolution? Other countries – notably France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden – had great universities and well established scientists and laboratories. Why did Britain create the industrial surge while others followed?

That’s the question that Ralf Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr address in their working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Their short answer: Britain didn’t have more geniuses than other countries, but it did have more tweakers and implementers.

Meisenzahl and Mokyr argue that Britain certainly had its fair share of “hall-of-fame” inventors. But many of those genius ideas would not have been turned into practical innovations if not for “…a group of skilled workmen who possessed the training and natural dexterity to … carry out the ‘instructions’ contained in the … blueprints, … build the parts … with very low degrees of tolerance, and … fill in the blanks when the instructions were inevitably incomplete.”

Meisenzahl and Mokyr try to distinguish between tweakers and implementers. Tweakers “…improved and debugged an existing invention.” Implementers were “…skilled workmen capable of building, installing, operating and maintaining, new and complex equipment.”

Meisenzahl and Mokyr identified 758 men and one woman (Elenor Coade “who invented a new process for making artificial stone…”) whom they could classify as tweakers or implementers. Each person in the database was born between 1660 and 1830. Meisenzahl and Mokyr studied the industries they worked in, what they did, how they were incented, and how they acquired their skills. Among their key findings:

- The apprenticeship system was critical – it produced not only knowledge but also the skill to produce finely tuned machines. It also provided talented youngsters with a stable environment while they acquired and honed their skills.

- Multiple incentives were available. Much has been made of the British patent system in spurring innovation. But the authors argue that a system of prizes was equally or more important. Organizations such as the Society of Arts offered prizes for the development of specific devices, such as a machine to manufacture lace. Many such prizes were awarded “on the condition … that no patent was taken out” – which allowed the innovation to spread more rapidly.

- A “mechanical culture” – the authors point out that, “The second half of the eighteenth century witnessed the maturing of the Baconian program, which postulated that useful knowledge was the key to social improvement. In that culture, technological progress could thrive.”

So Britain not only had its fair share of geniuses but also had a well organized cadre of people who could tweak, improve, and implement the ideas the geniuses handed on. Just think what Leonardo might have done.