Perverse Incentives

But is it for the right thing?

Let’s say I’m a successful sales rep at a business-to-business software company that’s trying to improve customer satisfaction. The company wants me to take good care of my customers, tell the truth, and make them feel loved.

At the same time, the company pays me based on how much software I sell each quarter. It’s in my best interest to sell as much as I can even if I have to stretch the truth a bit and promise more than I can deliver. Of course, stretching the truth and failing to deliver often result in lower customer satisfaction. So the company is incenting me to behave in ways that defeat its own objectives.

In Britain, this is known as the principal-agent problem. In this case, the principal is the company. I’m an agent acting on the company’s behalf. The problem is that the agent’s incentive (my commission) is different than the principal’s objective. We’re working at cross-purposes.

Paul Nutt and other American writers generally refer to this situation as a perverse incentive. According to Wikipedia, a perverse incentive”… has an unintended and undesirable result which is contrary to the interests of the incentive makers.”

Examples abound. We may strive for smaller government but we typically pay government managers based on how many employees they have, not on the profits they generate (since they generate no profits). We encourage orphanages to place children with families, but we pay subsidies based on how many children are in the orphanage.

The examples may sound bizarre but perverse incentives are all too easy to create. Nutt gives a particularly perverse example: the company that proclaims, “We will not accept failure.” While that may sound bold and brave, it sets up a perverse incentive.

Every company fails from time to time. When a failure occurs, it’s in the company’s best interest to analyze it, understand it, and use it as a teachable moment. But companies that don’t accept failure will never get a chance to do this. Employees associated with the failure will bury it as deeply as they can. Otherwise, they’ll get fired.

What should you do when you inevitably encounter a perverse incentive? The first thing is to make sure it’s known. Many times executives set lofty goals (“we will never fail”) without realizing just how perverse they are. Calling attention to perversity is a useful first step.

Second, it’s time to discuss alignment. We often think of alignment in terms of focusing on the same goal. That’s good but only if the incentives for achieving that goal are also aligned. A comprehensive and detailed review of incentives will help identify areas of misalignment. This is when a good HR department is worth its weight in gold.

Proving Praise Is Not Productive

This will improve your performance.

Here’s a little experiment for your next staff meeting. All you need is an open space about ten feet long and maybe three feet wide, two coins, and a flip chart.

Once you’ve cleared the space, set a target on the floor at one end of the ten-foot length. The target can be a trashcan, a book, a purse … anything to mark a fixed location on the floor.

On the flip chart, write down four categories:

- P+ — praise works; performance improves

- P- — praise doesn’t work; performance degrades.

- C+ — criticism works; performance improves

- C- — criticism doesn’t work; performance degrades

Now have one of your colleagues stand at the end of the ten-foot space farthest away from the target and facing away from it. Give her the two coins. Ask her to take one coin and throw it over her shoulder, trying to get it as close as possible to the target.

Observe where the coin lands. If it’s close to the target, praise your colleague lavishly: “That’s great. You’re obviously a natural at this. Keep up the good work.” If the coin falls far from the target, criticize her equally lavishly: “That was awful. You’re just lame at this. You better buck up.”

Now have your colleague throw the second coin and observe whether it’s closer or farther away from the target than the first coin. Now you have four conditions:

- You praised after the first coin and performance improved. The second coin was closer. Place a tick in the P+ category.

- You praised after the first coin and performance degraded. The second coin was farther away. Place a tick in the P- category.

- You criticized after the first coin and performance improved. The second coin was closer. Place a tick in the C+ category.

- You criticized after the first coin and performance degraded. The second coin was farther away. Place a tick in the P- category.

Now repeat the process with many colleagues and watch how the tick marks grow. If you’re like most groups, Category 3 (C+) will have the most marks. Conversely, Category 1 (P+) will have the fewest marks.

So, we’ve just proven that criticism is more effective than praise in improving performance, correct? Well, not really.

You may have noticed that throwing a coin over your shoulder is a fairly random act. If the first coin is close, it’s because of chance, not talent. You praise the talent but it’s really just luck. It’s quite likely – again because of chance – that the second coin will be farther away. It’s called regression toward the mean.

Conversely, if the first coin is far away, it’s because of chance. You criticize the poor effort but it’s really just luck. It’s quite likely that the second coin will be closer. Did performance improve? No – we just regressed toward the mean.

What does all this prove? What you tell your colleagues is not the only variable. A lot of other factors – including pure random chance – can influence their behavior. Don’t assume that your coaching is the most important influence.

However, when we do studies that control for other variables, praise is always shown to be more effective at improving performance than criticism. I’ll write more about this soon. Until then, don’t do anything random.

(Note: I adapted this example from Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow. I think Kahneman may have adapted it from Edwards Deming’s experiment involving a fork and different colored balls.)

MOOCs and Me – 2

I can teach from anywhere.

So, what about it? Will MOOCs destroy academic life as we know it? Or will they be more like correspondence courses – an interesting niche but only a niche? As a teacher of MOOC-like courses, I do have an opinion. (See yesterday’s post for the background to this burning question).

Here’s what MOOCs are good for: transferring structured bodies of information and testing to see that it was accurately received. Actually, the testing is still a bit slippery. It’s not always clear who is actually taking the test. However, I think that will be worked out over the next couple of years with proctored exams and/or new forms of identification.

Here’s what classroom-based education is good for: growing up. MOOCs can’t teach you much about integrity, social interaction, clear thinking, mature judgment, and the responsibilities of adult life. Campus education – especially residential campus education – can teach you far more about living than MOOCs ever could. As David Brooks points out, morality is a group activity.

People who want to grow up will continue to choose campus-oriented higher education. People who want to earn professional credentials may find MOOCs are a much better choice.

What does this mean in practice? I think undergraduate schools will be relatively unaffected by MOOCs. There will always be good reasons to ship your kids off to college.

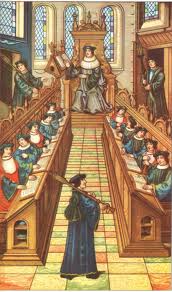

Further, some skills are more readily taught face-to-face, including negotiation, mediation, critical thinking, disputation, public speaking, rhetoric, and writing. Undergraduate schools will place increasing emphasis on these foundational skills. In this sense, they’ll be more like colleges of the 1930s and 40s than those of the 1980s and 90s.

Graduate education, on the other hand, is about to get Amazoned. Why would a student take a course in, say artificial intelligence, from a local professor when they could cover the same material (for free) from a world-renowned expert? When it comes to transferring a structured body of knowledge, MOOCs are hard to beat.

Is there any value of going to graduate school on campus? Well, foundational skills are still important. I teach Master’s students and I can attest that they would benefit by improving their ability to negotiate, speak persuasively, and write effectively. Additionally, on-campus programs may be better at helping students develop life-long networks. Actually, I’m a little skeptical that this is a significant advantage – social networks can fill the same need. Still, there’s probably a modest benefit from meeting your co-conspirators on campus.

To survive, I think that many graduate schools will shift their emphasis away from codified bodies of knowledge and toward the foundational skills. They can offer the bodies of knowledge through MOOCs. In their on-campus courses, they’ll focus on teaching the “softer” skills. In my experience, these are far more valuable than structured bodies of knowledge.

In terms of market positioning, I think it’s simple. The best grad schools in the future will position themselves along these lines: Any MOOC can teach you how the world works. We can also teach you how to work in the world.

(By the way, these opinions are my own and not those of any of my clients or employers).

MOOCs and Me – 1

Nothing’s changed.

As an adjunct professor at the University of Denver, I teach in University College (UCOL), the school’s professional and continuing education program. UCOL focuses on non-traditional students, especially people who have been out of school for some time and are returning to study for an advanced professional degree.

I teach at the Master’s level and most of my students are in their 30s and 40s. Many see the Master’s degree as a key to greater career opportunity. They’re mature and motivated. They’re focused on acquiring certified knowledge, not on growing up.

I teach my courses in two completely different formats: on campus and online. The on-campus courses meet one night a week. The online courses never meet at all – we interact with each other through a web-based electronic college.

I’ve taught on-campus courses off and on for many years. I know what I’m doing and I feel comfortable and confident in the classroom. On the other hand, when I started teaching online – two years ago – I felt very unsure of myself. Though I was very familiar with the technology, I didn’t know how to use it to teach effectively.

Two years later, I feel much more comfortable teaching through the web. In fact, in some ways, I prefer it. The major advantage is that I don’t have to be anywhere at any specific time. As long as I have an Internet connection, I can teach my class.

The same is true for my students. In my online classes, I typically have students in six to eight different states and two to three different countries. Through the magic of the web, I can potentially reach hundreds, even thousands of students.

And that brings us to MOOCs – the Massive Open Online Courses that are roiling college campuses across the country. MOOCs take some of some of our best professors — often from places like Stanford, MIT, and Harvard – put them in front of a camera and ask them to teach thousands of students across the web.

MOOCs are massive; some enroll 50,000 students or more. They’re open; anyone with an Internet tap can register. They’re also free. Yikes!

MOOCs challenge virtually everything we do in universities today. A fundamental problem of higher education is that it hasn’t increased productivity for 700 years or so. While every other industry has increased productivity and thus can offer more for less, higher education offers the same for more. Without productivity increases, tuition will always rise at least as fast as inflation.

MOOCs promise to change that. Put a great professor online and – presto! – we can educate the masses. We can also save a lot of money. Why should states pay millions to support brick-and-mortar campuses? Why should students spend thousands to attend schools with second-string faculty? Why indeed?

So, will MOOCs destroy academic life as we know it? Or will they be more like correspondence courses – an interesting niche but only a niche? As a teacher of MOOC-like courses, I do have an opinion. But, let’s talk about that tomorrow.

Cicadas and Prime Numbers

Here in the United States, we’re suffering through a cicada plague. The insects lie dormant for 17 years, then dig themselves out of their little holes, mature, mate, lay eggs, and die. The little ones lie dormant for 17 years before repeating the process.

Here in the United States, we’re suffering through a cicada plague. The insects lie dormant for 17 years, then dig themselves out of their little holes, mature, mate, lay eggs, and die. The little ones lie dormant for 17 years before repeating the process.

When I read about the 17-year cycle, I thought to myself, “Hmmm… 17 is a prime number. I wonder if there’s any significance to that?” It turns out that it’s very significant. By coming out on a prime year, the cicadas avoid predators that arrive in two-, four- and eight-year cycles. Read more about it here.