Information Science: Less Is More

If you’re following this year’s presidential campaign, you’re probably experiencing a fundamental law of information science: the more

frequently a signal is repeated, the less information it carries. The law has many practical implications. It’s why you can buy a vowel on Wheel of Fortune. Vowels are frequently repeated so they carry very little information. So you can buy one cheap.

The law is also why people start to ignore you if you keep repeating yourself. You’re adding no new information to the conversation, so why pay attention? This is a big problem for the presidential campaign. The two parties have been repeating essentially the same thing for two years now. The candidates have had nothing new to say for months. The talking heads repeat the same signals over and over but they’re adding no new information to the party. For many of us, it’s time to tune out.

There’s a difference, however, between signals and messages. Most companies should keep their core message consistent over time. Consistency builds trust and trust builds brands. To keep the message resonating with your audience, however, you’ll need to change the signal from time to time. In other words, you’ll need to find new ways to say the same thing. In brand building, this is what creativity is all about. You’re not trying to create a new message (in most cases). You’re trying to find new ways to deliver the same message so the audience will continue to listen.

Just think of how many times you’ve seen the signal, “Safety First”. It’s a good message but a tired signal. It’s become part of the wallpaper. We no longer pay attention to it. If you want us to behave safely, you’ll need to change the signal. How about this: “You Don’t Want to Die, Do You?”

Now it’s time for me to change the signal while keeping the message the same. Stop reading and click on the video.

Branding: Why Do They Buy?

When I lived in Stockholm, I was responsible for customers throughout Scandinavia. One of my favorite customers was Dale of Norway, the creators of richly patterned, thick wool sweaters. The sweaters are very popular with winter sport enthusiasts in my home state of Colorado. They’re stylish and they’re practical … and therein lies a tale.

I visited Dale of Norway’s headquarters and met their CEO. The company is located in a picturesque little town called Dale. (We call it Dale as in Chip and Dale but the Norwegians pronounce it Darla). When I met the CEO I mentioned that I was from Colorado and that my wife and I were both customers. The conversation went something like this:

CEO: “Let me guess. You have one sweater and your wife has three.”

Me (surprised): “Yes. How did you know?”

CEO: “Women see our sweaters as fashion statements and they’re willing to buy more than one. Men see them as a high quality product that will last a life time. If it will last a life time, why would you ever buy more than one?”

Me: “I wish I understood my customers as well as you understand yours.”

There are a couple of lessons here. First, sometimes a satisfied customer is just that: satisfied. I was a very satisfied Dale of Norway customer. If you did a customer satisfaction survey, I would be right at the top. But I was generating exactly zero revenue for the company.

One of Dale of Norway’s challenges was to overcome the satisfied customer curse. They needed to give me (and even my wife) more reasons to buy. To complement their heavy weight sweaters, they introduced two new product lines — mid-weight sweaters and lighter weight accessories. I’m now the proud owner of a mid-weight sweater and some long underwear. I’m still satisfied but, more importantly, I’ve generated new revenues for Dale of Norway.

The second lesson: different people buy for different reasons. Don’t ever assume that what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. To the maximum extent possible, live with your customers. When you see the world through their eyes, you’ll find that different groups see your product differently. There’s nothing surprising in that — it’s just segment marketing. Unless you understand how each segment thinks, you’ll never communicate effectively with them. One message does not fit all.

The third lesson? Dale of Norway makes great sweaters, gloves, mittens, and scarves. So get out there and buy one … or two … or three. You can find them here.

Dunbar’s Number: Why My Clients Hire Me?

I’ve noticed a pattern among my clients. Many of them are small software companies with good ideas that are growing rapidly. When they first call me, they have approximately 150 employees. I’ve often wondered, what is it that triggers a problem — and a call to an outsider — at 150 employees?

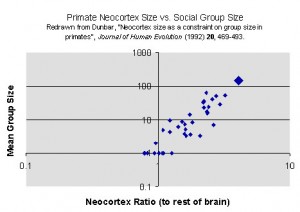

Then I discovered Dunbar’s number and the pattern started to make sense. Robin Dunbar, a British anthropologist, is an expert on the social lives of monkeys. (Wouldn’t you love to have a job like that?) Dunbar made an interesting observation: Monkeys with small brains have small social circles. Monkeys with larger brains have larger social circles. Actually, it’s not total brain size — it’s the size of the neocortex, the area of the brain where we do our abstract reasoning. In Dunbar’s charts, you’ll find a distinct up-and-to-the-right relationship between the size of the neocortex (relative to the rest of the brain) and the size of the social group.

So, you might wonder, how does this affect the lives of large-brained primates known as humans? How big is our “natural” social group? Funny you should ask. Dunbar frames the question this way: what’s the largest number of people in which it’s possible for everyone to know each other and also to know how everyone relates to everyone else? The answer is slippery but it seems to be around 150 people (plus or minus, oh, say 30).

How many for humans?

If you search the topic on the web, you’ll find a number of observers arguing for a higher number. (I didn’t find any arguing for a lower number). On the other hand, you’ll also find observers who claim that 150 occurs frequently and “naturally” in traditional societies. Apparently, the Roman Legions were divided into companies of 150 men. Church parishes in 18th century England contained 150 people. If your parish grew bigger, the bishop would campaign for an additional church.

How does Dunbar’s number affect organizations? Generally speaking, a smaller organization can be fairly loosey-goosey. We all know each other and we all know how we relate to each other. We don’t need a lot of structure. Above 150, however, organizations start to get more bureaucratic. According to Wikipedia, “…analysts assert that organizations with populations of people larger than Dunbar’s number … generally require more restrictive rules, laws, and enforced norms, to maintain a stable, cohesive group.”

Maybe this is why companies call me when they reach about 150 employees. They’re growing up and they’re feeling the growing pains. It’s not as simple as it used to be. In fact, it’s getting rather complicated. I hope they keep calling me. I’m becoming a bit of a specialist.

You can find Dunbar’s original article here.

Barry and Mitt — Who Won?

Though nobody landed a knockout blow in tonight’s debate, Mitt Romney did exactly what he wanted to do: position himself as a legitimate alternative to the president. Romney came across not as some right-wing crank but as a thoughtful, intelligent candidate who is reasonably articulate. Surprisingly, Romney actually seemed more human than President Obama who came across as wonkish and overly abstract. Obama looked rusty to say the least.

I expected the President to play defense but he seemed downright tentative at times. His body language suggested that he really didn’t want to be there. On the split screen, he rarely looked at Romney. He also had many more verbal tics than Romney — more hemming and hawing and umms. He also said “I tried” far more often than necessary. “I tried to do this”, “I tried to do that”. It seems to me that the President of the United States should say “I did” more than “I tried”. He seemed apologetic rather than confident.

As several commentators have mentioned, this was a “wonkfest”. The satirist, Andy Borowitz, suggested that we join him in watching the Weather Channel — much more interesting. Twitter lit up with discussion about whether Romney would really kill Big Bird. Twitter was almost universal in criticizing Jim Lehrer. More than one Twitter commentator asked if he was a replacement ref.

I found Intrade much more interesting to follow than Twitter. The last time I wrote about Intrade (back in July) the prediction market gave Obama a 56.2% chance of being re-elected. Since the conventions and various mis-steps by Romney, the market has trended toward Obama. Last week, Intrade betting predicted an almost 80% chance of Obama winning. The line started to drift back during the week and was in the low 70’s when the debate started. As the debate got under way, Obama’s stock started to fall and stayed down. I checked a few moments ago and Obama’s chances had dropped to about 66% — down almost 6% for the day. Clearly, the prediction markets think Romney won the debate though they’re still saying that Obama has a 2/3 chance of being re-elected. I’m sure Obama will be sharper in the next two debates but Romney has shifted the dynamic and given his campaign a lift. Now the race is on.

Barry and Mitt: Body Language

I spend a lot of time studying rhetoric and the logic of giving a persuasive presentation. Many of my posts on this website deal with the content and organization of a good speech. I’ve written a bit about body language (here) and I can usually help a speaker feel comfortable in front of an audience. (That’s well over half the battle).

Today, however, let’s learn from the experts: Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. The New York Times has an excellent article, including interactive graphics, on gestures and movements that these orators make to emphasize points and to gain agreement with the audience. They both appear to be masters of the art — so take a peek here.