Greetings from quit.snacks.humid

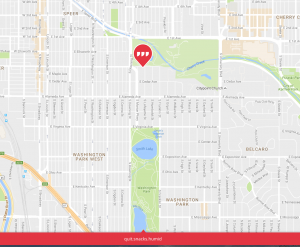

My house — quit.snacks.humid

How do you tell someone where you are? Most of us would use some form of a postal address to identify our location. But what if you’re in a place that doesn’t have a postal address? In other words … most of the world.

If there’s no postal address, I might use latitude and longitude. For instance, our home is located at 39.714549 latitude and -104.971346 longitude. If you understand the system, you’ll realize that my house is 39 degrees north of the equator and 104 degrees west of the prime meridian that passes through Greenwich, England.

(I have an 18th century French map that gives longitude as the number of degrees east or west of Paris. It was part of a long-running dispute about where, precisely, the center of the world is.)

Longitude and latitude give us precise locations, but they’re not human friendly. It’s like noting that the current temperature is 287.039 degrees Kelvin. That’s accurate but not terribly meaningful to most humans.

So, is there a way to map the world that would be easier for humans to manage? Well, how about we divide up the entire surface of the earth into squares that are approximately three meters per side? Each square is nine square meters or roughly 90 square feet. As you’ve no doubt calculated by now, we would need about 54 trillion such squares.

That may sound complicated but, really, how hard is it to manage 54 trillion squares? The researchers at What3Words – a start-up company in London – figured out that you only need 40,000 words in three-word combinations. That yields about 64 trillion combinations – enough to address the world and have a few trillion combinations left over.

In the world of What3Words, our home address is quit.snacks.humid. It’s easy to remember and precise enough to guide you to our front door. If I wanted to guide you to our driveway, I would instead use the words refuse.fake.limbs. If I wanted to send you to the highest summit in Colorado – a place that doesn’t have a postal address – I would send you to penned.metro.inspections.

According to What3Worlds, the system is already in use to deliver mail in unaddressed areas like Mongolia or the favelas of Brazil. Similarly, Steven Spielberg is using What3Words addresses to get his actors and crew to the right place at the right time as he films his latest movie. I can imagine Colorado’s Alpine Rescue Team guiding rescuers to acutely.jumbo.popcorn rather than saying, ”The injured party is about 3.3 miles northeast of the Mt. Elbert summit on the east flank of a small ravine.”

What3Words already has some interesting use cases and, if it develops fully, it should help us with logistics, emergency services, scheduling, and materials management. But its real potential comes from the fact that it’s released not as a solution but as a platform. As we know, (click here, here, and here) platforms are innovations that generate innovations. As other application developers adopt and adapt the platform, we could see a rich ecosystem of solutions that even the What3Words folks can’t imagine today.

By the way, I’m taking a few days off. If you need me, I’ll be at tent.quarrel.charm.

Are You A Super-Recognizer?

I recognize you!

If you met somebody from your third grade class, would you recognize her? How about someone you last saw a decade ago at a company where you used to work? How about a person you saw in a mug shot at the Post Office?

If you answered “yes” to any of these, you may be a super-recognizer. Super-recognizers literally never forget a face. They may also give us the next great leap forward in law enforcement.

We haven’t known about super recognizers for very long. Over the past 20 years or so, researchers have learned a great deal about the opposite condition known as prosopagnosia or face blindness. Some people – perhaps two percent of the population — just can’t remember faces. They’re “blind” to the faces around them. They can interact with you perfectly well while they’re with you but they won’t recognize you the next time they see you.

Researchers initially thought that this was a binary condition – either you were normal or you were face blind. Then someone had the bright idea that the ability to recognize faces might be distributed along a normal curve. If face blind people are clustered under one tail of the curve then the other tail should include people who are exceptionally good at recognizing faces – the super-recognizers.

It turns out that they were right. In 2009, Richard Russell and his colleagues published the first academic paper on the subject: “Super-recognizers: People with extraordinary face recognition ability”.

It seems like a typical academic topic but the story took an unusual twist when the Metropolitan Police Service in London took up the idea. As detailed in a recent story in The New Yorker, the Met experimented with super-recognizers as detectives. London has more security cameras than any other city in the world but couldn’t turn the images into a crime-fighting advantage. The city had millions of low-resolution images of potential criminals and nobody to interpret them.

The Met tried to change that with an organized team of super-recognizers. The super-recognizers browse through mug shots and then review footage from security cameras that have recorded a crime. In a surprising number of cases, the super-recognizer has an “aha” moment and links a miscreant to a mug shot.

How good are they? The Met calls super-recognizers “the third revolution in forensics” after fingerprints and DNA evidence. The Met solves about 2,000 cases a year with fingerprints and another 2,000 with DNA. By comparison, the super-recognizers solve about 2,500 cases.

At this point, you may be wondering just how good you are at recognizing faces. Here’s how to find out – the Cambridge Face Memory Test. Click here and you can take the same test that the Met uses to screen applicants for the super-recognizer team. If you get a high score, you might just apply for a position with your local police force.

Managing The Matrix

Task: Assemble the best team.

One of my largest clients is re-engineering its organization to focus on functions rather than geographies. It’s a classic move from top-down management to matrix management. I think it’s very much the right thing to do but it’s making some of the managers nervous. How does one shift from managing a team to managing a matrix?

I went through a similar transition at Lawson, the last major software company that I worked for. We transitioned from geographies – Sweden, Western USA, Australia/New Zealand – to global teams that focused on vertical markets like healthcare, food and beverage, and fashion. We focused on industries rather than geographies and became expert advisors to our customers.

And what did I learn about managing in a matrix? Here are the key ideas that stood out for me.

Connectors succeed – in a geographic organization, a manager gets to know her team and learns how to accentuate their strengths and minimize their weaknesses. Team members are often physically close to each other. There’s no need to connect them; they’re already connected. In a matrix, the ability to connect people is the most important single skill. People who are natural connectors are often the best matrix managers.

Diplomacy counts – diplomacy is a useful skill for any manager. It’s especially important in a matrix. In a top-down organization, a manager could simply give orders without much tact or diplomacy. Not so in a matrix. A matrix manager is forever building teams – one team to address Issue X, and another to address Issue Y. A matrix manager is always recruiting and needs a positive attitude, good diplomatic skills, and a good understanding of what motivates people.

A good manager can build all-star teams – let’s say I wanted to sell Lawson software to the Swedish fashion house, Filippa K. With the right diplomatic and connecting skills, I could assemble an all-star team to sell the account. My team might include a design expert from New Zealand, a cut-and-sew expert from New York, and a retail expert from Stockholm. I pull them together and focus them intently on the task of selling to Filippa K. Once they sell the account, the team dissolves and the team members reassemble — perhaps with other teammates – to focus on a different project. The good news is that a matrix manager gets to work with all-stars all the time. The not-so-bad news is that a successful matrix manager needs to continually assemble and re-assemble teams in ever-changing patterns.

Talent spotting becomes more important– in a geographic organization, employees do multiple things in a designated area. They become jacks-of-all-trades. In a matrix organization, employees are much more likely to specialize in a given function. They can master the skill. The successful matrix manager knows how to spot the most talented employees and recruit them to her (temporary) team.

Flexibility and adaptability count – flexibility is the strongest point of matrix organization. Managers can quickly assemble and re-assemble teams based on changing needs. This only works if managers are equally flexible. Managers must be fluid; they can’t stay attached to a permanent structure. There is no permanent structure.

Managers must work effectively with each other – in a matrix, an employee often has more than one manager on a given project. For instance, that retail expert from Stockholm would report to me temporarily while working on the Filippa K account. At the same time, she would also report to the overall head of the retail team, who might be located in Melbourne. It can get confusing and roles need to be clearly defined. At the same time, managers need to work effectively with their peers cross the matrix. If I have a beef with the manager in Melbourne, things will go downhill quickly. Again, diplomacy and good communication are key ingredients for success.

The matrix changes the culture – in geographic organizations, teams may easily fall into competition with each other. I would have no incentive to lend my retail expert to another geography. That would only crimp my chances of making my number. A matrix, on the other hand, emphasizes cooperation. If a manager doesn’t make her all-stars available, she doesn’t get access to other all-stars. Sharing becomes more important than competing.

Ultimately, good managers have nothing to be afraid of in a matrix organization. Even in traditional top-down organizations, good managers are likely to be effective communicators and motivators with good diplomatic skills. Those are the same skills that are required to succeed in a matrix.

Altruism and Sex

My genome is healthy.

Altruism is traditionally defined as: “behavior by an animal that is not beneficial to or may be harmful to itself but that benefits others of its species.” So here’s a simple question: why would anyone be altruistic?

One answer has to do with our relatives. Sociobiology suggests that all living creatures share one fundamental goal: to propagate our genes into future generations. Of course, the most direct way to propagate our genes is to reproduce.

But we can also propagate our genes by supporting our genetic relatives. So I might behave altruistically toward my sister because she shares much of my genome. If she reproduces successfully (and her children do as well), then some of my genetic heritage is passed on to future generations. So it pays to be nice to my sister. (It took me a long time to figure this out).

But why would anyone be altruistic toward someone who is not a genetic relative? According to Steven Arnocky’s recent paper in the British Journal of Psychology it has to do with another fundamental human drive: sex.

You may recall that competition for sex is a key element in maintaining the overall health of a species. When there is a fair amount of competition among males, females are remarkably good at picking out the best mates. What does “best” mean in this sense? The best men for producing healthy offspring who can in turn produce healthy offspring of their own.

So how do females know which males will produce the best offspring? Some of it is physical. For instance, females strongly prefer males who are symmetric rather than asymmetric. Being symmetric is, apparently, a good marker of genetic health.

Behavior also plays a role. We know, for instance, that creativity plays a strong role in mate selection – for both men and women. Ornamental creativity is especially attractive. Strictly speaking, ornamental creativity is not essential to survival. So those who display this trait are effectively advertising “I have more than enough to survive plus some left over for ornamentation. I have an abundance of what you want.”

According to Arnocky’s paper, non-kin altruism plays a similar role to creativity. It’s a behavior that is desirable to the opposite sex. The study used two different methods to measure altruism and then correlated the degree of altruism with sexual activity. Those who scored higher on altruism, “…reported having more sex partners, more casual sex partners, and having sex more often within relationships.” The correlation was stronger for men than women, suggesting that altruism is more important for women selecting men than for men selecting women.

In an interview, Arnocky summed up the results by noting that, “”It appears that altruism evolved in our species, in part, because it serves as a signal of other underlying desirable qualities, which helps individuals reproduce.”

Based on Arnocky’s findings, we may have been defining altruism improperly. The classic definition says that altruism doesn’t benefit the individual but does benefit the species. But Arnocky’s paper points out a very direct benefit to the individual – better mates and more of them. Given this, we need to re-phrase our initial question. It probably should be: why wouldn’t everyone be altruistic?

(Less technical summaries of Arnocky’s paper are here and here).

Another Reason For Female Executives

Which gender norms should we adopt?

Want to get stuff done? You may need to compromise occasionally. Who’s better at that? Who do you think?

A recent study in the Journal Of Consumer Research (abstract here; pdf here) suggests that men working with men tend not to compromise. By contrast, men working with women or women working with women are more likely to find the middle ground.

The article, by Hristina Nikolova and Cait Lamberton – professors at Boston College and the University of Pittsburgh respectively — focuses on consumer behavior and is probably most relevant to marketing strategists. But I wonder if it doesn’t have much broader implications as well.

The study revolves around the compromise effect, which is well understood in marketing circles. Let’s say that you want to buy a car and you have two decision criteria: efficiency and prestige. Car X is clearly better on efficiency and OK on prestige. Car Y is clearly better on prestige and OK on efficiency. Car Y is also more expensive than Car X.

Which one do you buy? It’s a tough choice. So the salesperson introduces the even more expensive Car Z, which is even better on prestige than Car Y. Now Car Y is the compromise choice – it’s OK on efficiency and pretty good on prestige. With three choices available, Car Y is not the top of the line on either criterion but it’s acceptable on both criteria. The compromise effect suggests that you’ll buy Car Y.

The compromise effect has been demonstrated in any number of studies. Indeed, it’s why restaurants often add a very high-priced item to their menus. The item probably doesn’t sell very often but it makes everything else look more reasonable.

But what if you’re making the decision with another person? This hasn’t been studied before and Nikolova and Lamberton focus their attention on decisions made by two people acting together (also known as dyads). The authors looked at three different dyads:

- Male/male

- Female/male

- Female/female

Under five different conditions, Nikolova and Lamberton found essentially the same results. First, the compromise effect seems to work “normally” with female/female and female/male dyads. Second, the compromise effect has much less impact on male/male dyads. Such dyads tend to move toward one of the extremes – either Car X or Car Z in our example.

Why would this be? The authors suggest that it has to do with gender norms coupled with the act of being observed. They write, “Normative beliefs about women’s behavior suggest that women should be balanced, compassionate, conciliatory, accommodating, and willing to compromise….” Male gender norms, on the other hand require, “…men in social situations to be maximizers, assertive, dominant, active, and self-confident; their decisions should show leadership, … high levels of commitment … and decisiveness….”

For both genders, being observed influences the degree to which an individual adheres to the gender norms. If you know you’re being observed – and/or that you will need to defend your choice later – you’re more likely to behave according to your gender norm. Interestingly, men working with women tend to adopt more of the female gender norms.

Nikolova and Lamberton focus exclusively on consumer choice but I wonder if the same dynamic doesn’t apply in many other decision-making situations as well. Men may be willing to compromise but they don’t want to be seen as compromisers. If you need to compromise to get something done, it helps to add a woman into the mix.

Indeed, I was struck by the fact that the same day I discovered the Nikolova-Lamberton article, I also read about Tim Huelskamp, a Republican congressman from western Kansas. According to the New York Times, Huelskamp is a “hardline conservative member of the Freedom Caucus” who “quickly earned a reputation for frustrating Republican leaders…” after he was elected in 2010. Yesterday, a more moderate challenger defeated Huelskamp in the Republican primary. As one voter noted, ““I don’t mind [Huelskamp’s] independent voice, but you’ve got to figure out how to work with people.” Perhaps the good people of Kansas should elect a woman to replace him.