What Makes You Creative? Part 1

I’m smart but also naive.

What makes people creative? Can you exercise your creative “muscles” to become more creative?

I’ve read a lot trying to answer these questions. The best single source of answers I’ve found is Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Creativity: Flow and The Psychology of Discovery and Invention. Csikszentmihalyi and his associates interviewed more than 100 people who had created fundamental changes in their domains.

After sifting and sorting the interviews, Csikszentmihalyi writes that the one word that best describes the creative personality is complexity. If you think of personality traits as continuums, creative people tend to show up at both ends. For instance, one continuum might run from energetic at one end to lazy at the other. Csikszentmihalyi observes that creative people are highly energetic and focused at some times but lethargic at other times. They can work very hard for extended periods of time but then “hibernate” to re-charge their batteries. Many interviewees noted that a daily nap is essential to their creative process.

Csikszentmihalyi identifies ten different pairs of opposing traits that occur commonly in creative personalities. Let’s look at three today. I’ll cover the rest in future posts.

Creative individuals have a great deal of physical energy, but they are also often quiet and at rest.

Creative individuals can work long hours while maintaining a high level of energy. According to Csikszentmihalyi, the most important aspect of this is that creative individuals can manage their energy levels more or less on their own. As Csikszentmihalyi writes, “When necessary they can focus it like a laser beam; when it is not, they immediately start recharging their batteries.”

Creative individuals tend to be smart, yet also naive at the same time.

How smart are they? Pretty smart but typically not geniuses. It seems that an IQ of about 120 is a dividing line. Up to 120, creativity seems to increase with intelligence. As IQ rises above 120, creativity seems not to increase much. Other factors are more important.

If intelligence (as measured by IQ) leads to convergent thinking – finding a well-defined answer to a well-defined problem – then naiveté leads to divergent thinking. Csikszentmihalyi defines this as “the ability to generate a great quantity of ideas…or the ability to switch from one perspective to another….”

An issue with divergent thinking is that it’s often difficult to distinguish a good idea from a bad idea. Several of Csikszentmihalyi’s respondents say that the main thing separating them from less creative individuals, is that they are better able to predict which problems are soluble and which are not.

A third paradoxical trait refers to the related combination of playfulness and discipline, or responsibility and irresponsibility. There is no question that a playfully light attitude is typical of creative individuals.

In Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman writes about the sheer joy of working with his colleague, Amos Tversky. They thought deeply – but differently — about the problems they studied and seemed to have a lot of fun.

As Csikszentmihalyi points out, doggedness is the necessary counterpart to playfulness. Being playful can get you started but it rarely gets you finished. Perhaps that’s why Edison said, “Invention is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration”

Can these traits be taught? Can we become more creative? Within limits, I think so. I suspect that intelligence can’t be radically altered but certainly we can learn to be naïve. Divergent thinking is taught in most creativity workshops. Playfulness shouldn’t be that hard to learn. Doggedness may be a bit more difficult but, with the proper motivation, it too can be mastered. As for energy management … well, how hard is it to learn to take a nap?

(To read the other articles in this series, click here and here).

Innovation, Persuasion, and Listening

I’m listening.

I struggle to be a good listener. When I’m engaged in an intense conversation, I’m often: 1) Framing my response; or 2) Thinking about a solution to the problem at hand. Of course, when I’m thinking about something else, I’m not really listening — I’m maneuvering. More importantly, I’m not being persuasive. If the other side thinks I’m not listening, they’re less likely to be persuaded to my point of view.

So I was pleased to find a recent McKinsey white paper by Bernard Ferrari titled “The Executive’s Guide to Better Listening”. (Click here). As Ferrari points out, “Listening is the front end of decision making.” If you want your company to be more innovative, you’ll need to make a number of critical decisions. If you’re a good listener, you’ll make better decisions and be more persuasive. That’s the best double play since Nellie Fox and Luis Aparicio.

So how do you become a good listener? Ferrari suggests three critical skills. First, show respect. Respect breeds confidence and trust. (This is essentially the same lesson that Greek rhetoric teaches — build trust first). If you’re a manager, you probably have a complex set of responsibilities. You can’t know everything about every facet of your domain. By respecting your teammates, you will naturally draw them into the conversation and learn from them. If you simply jump to a solution (as I sometimes do) you short circuit the entire process. Not only do you miss out on any advice about the current situation, you also teach your colleagues not to offer advice in the future. This doesn’t mean you should avoid incisive questions. Au contraire, the more the better to keep the conversation flowing.

Second, keep quiet. Ferrari suggest a variation of the 80/20 rule — let the other person speak about 80% of the time while you speak only 20% of the time. (This also works when you’re on a date — always encourage your partner to speak more than you do). This is a particularly hard one for me. I want to jump in and share my opinion because I know it’s … well, brilliant. But often times, I wind up answering the wrong question or chasing an irrelevant tangent because I’ve spoken too soon. As Ferrari notes, it’s important to take your time: “…if a matter gets to your level … it is probably worth spending some of your time on it.”

Third, challenge assumptions. This doesn’t just mean that you challenge other people’s assumptions. It also means that you encourage your colleagues to challenge your assumptions. As Ferrari writes, “… too many executives … inadvertently act as if they know it all … and subsequently remain closed to anything that undermines their beliefs.” Ultimately, “The goal is common action, not common thinking…” So, be explicit. Let your colleagues know that you don’t know everything and welcome their questions, especially the challenging ones.

I’ve found that it’s not easy to master these three skills. But when I do succeed, I learn more and, frankly, I have more fun. That makes me a better manager and a better teammate. And that makes my company more innovative.

Innovation: Five Trends

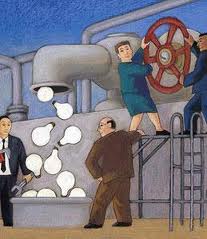

Good ideas. How do we integrate them?

We know a lot about what innovation looked like in the past. What does it look like in the future?

That’s the question that Arthur D. Little (ADL) researchers asked of more than 100 Chief Technical Officers and Chief Innovation Officers in a recently published white paper. (Click here). The ADL researchers identified five key trends that should drive innovation management over the next decade. Today, I’ll summarize the trends. In the future, I’ll to delve into each one in more detail.

The most important trend — as rated by the CIOs and CTOs –is customer-based innovation — “finding new and more profound ways to engage with customers and develop deeper relationships with them.” B2B companies have traditionally emphasized customer-based innovation. After all, B2B companies have relatively few but relatively deep customers relationships. According to ADL, however, even B2C companies are now focusing less on the product itself and more on the “ownership experience”.

The second trend is proactive business process innovation. I read widely on innovation and almost everything I see has to do with product innovation. ADL says this is changing but that “there is still much to be done to develop a convincing innovation management approach that is sufficiently systematic and repeatable to generate new, innovative business models.” The first objective is to deliver “thick value” — long-term relationships with multiple touch points as opposed to “thin value” transactions.

Third is frugal innovation which may be better known as reverse innovation. Rather than innovating in high-value (and high-cost) knowledge economies, frugal innovation uses low-cost emerging economies to create products with “less” rather than “more”. Developing a new idea in India, say, will often result in a lower cost product than developing the same idea in Europe. Frugal innovation often changes entire supply chains rather than individual products.

Fourth is high speed/low risk innovation. The CIOs and CTOs say they expect even more time-to-market pressure in the next decade. Additionally, they think that product life cycles will continue to accelerate. At the same time,the customer’s ability to identify and publicize flawed products has expanded dramatically. So, even as the pressure to accelerate continues, the pressure to deliver flawless products also increases. How do you deliver high quality products in ever faster cycles? You change your business process. ADL expects to see more gradual product rollouts coupled with more pervasive and proactive post-sales service.

Integrated innovation is the last major trend ADL identifies. The idea here is to take innovation processes out of the New Product Development (NPD) domain and integrate them into all business processes and strategies. Among other things, this requires collaboration across traditional functional divisions. Organizational development experts will focus on building horizontal layers to replace vertical silos. Creating an Enterprise Architecture (EA) to manage knowledge and information could drive this trend.

So, five trends in innovation management – each is interesting in and of itself. Over the next few weeks, I’ll delve into each one in more detail and identify the prerequisites for success in each one. Stay tuned.

Innovation: Boeing versus Airbus

To innovate successfully, you need a strong vision of the future. What will your customers want in ten or 20 or 30 years? If you can picture that, you can start creating innovations today that will put you in the right place when the future arrives.

To innovate successfully, you need a strong vision of the future. What will your customers want in ten or 20 or 30 years? If you can picture that, you can start creating innovations today that will put you in the right place when the future arrives.

That’s one of the reasons I’m fascinated by the dogfight between Boeing and Airbus. They clearly have very different visions of the future of commercial aviation. Different visions produce very different airplanes.

Let’s start with what they agree on. Both Boeing and Airbus believe that the future belongs to the efficient — as measured by cost per passenger mile. Boeing has chosen to work on numerator — operating cost — while Airbus is focused on the denominator — passenger miles. This produces two very different airline experiences: point-to-point for Boeing versus hub-and-spoke for Airbus.

Let’s say I want to fly from Denver to Brisbane, Australia. There’s some demand for travel between the two cities but it’s not huge. So how would the experience differ on Airbus versus Boeing? In the Airbus scenario, I would fly to a regional hub — maybe Los Angeles — and then join 800 other passengers on an A380. The huge number of passengers dramatically lowers the cost per passenger mile. I would then fly the A380 to another regional hub — say Sydney — and then transfer for a short flight to Brisbane.

Boeing takes a different tack. Boeing essentially says, if there’s not much demand, let’s build a smaller plane that airlines can operate profitably on “long, thin routes”. Thus, the Boeing 787 — a light weight, twin engine, long distance plane. In the Boeing vision, I would board a 787 in Denver and — 15 hours later — get off in Brisbane. I can fly from point to point rather than transferring in mega-hubs.

Personally, I prefer the Boeing vision. But that’s not really the point here. The point is that your vision leads you to the type of innovations you deliver. Boeing and Airbus clearly have different visions of the future. Thus, they’re building very different planes. It may be that one is right and the other is wrong. Or maybe there’s room for both. No matter how it plays out, both Airbus and Boeing are making bet-the-company gambles on their visions.

So what’s your vision of the future? What will your customer want in one year? Or five years? Or 20 years? You can’t predict the future — at least not the details — but you can create a strong vision of what services and products your customers will want. That can help you create the innovations that will get you safely to the future.

By the way, the first long, thin route from Denver starts in mid-2013 — a non-stop flight from Denver to Tokyo on a 787. That’s a flight that Suellen and I need to take.

Leadership and Motivation

Napoleon once said, “When I realized that men were willing to die for bits of colored ribbon, I knew I could rule the world.” It’s a wholly cynical sentiment but Napoleon was famous for creating and distributing military awards, citations, ribbons, medals, and orders. And for many years, it worked — his troops were highly motivated.

Several hundred years after Napoleon, Tony Blair said something quite similar (though I can’t find the exact quote). A journalist noted

Over to you, Tony.

that Blair was quite the egalitarian and asked if he might not abolish the English system of knighthoods and lordships. Blair responded (more or less), “You must be joking. The system is the most productive, least costly innovation engine in the world. It’s amazing how hard people will work for a tap on the shoulder from the Queen.”

Surprised that the English and the French might agree on something? Perhaps they’re on to something. The moral of the story is that praise and recognition can motivate people even more than money can. I’m surprised that we don’t use it more. I’ve seen far too many managers who are slow to recognize achievements and grudging with their compliments. I’m surprised because, as Tony Blair notes, praise is an inexpensive and productive way to motivate people.

Here’s an experiment. Ask a married couple what percentage of the house work each one does. Ask them separately so one doesn’t hear the other’s answer. Add the two percentages together. Almost certainly, the sum will be greater than 100%. Why? Because each member of the couple has a very good subjective sense of how hard they work. On the other hand, they don’t have that same sense for the other member of the couple. Each one knows how hard they work. It’s quite common that each one feels they deserve more recognition.

Similarly, after a complex project is concluded, ask each member of the team, “What percentage of the value did you personally deliver?” (Again, ask them separately). If the project team has six or more members, when you sum the responses the answer will very likely be greater than 200%. Each person has an inflated sense of how much they contributed.

As a manager, what should you do? The simple answer is to give more praise than you think is absolutely necessary. In fact, give about twice as much as you would normally do. After all, the French and English can’t both be wrong.