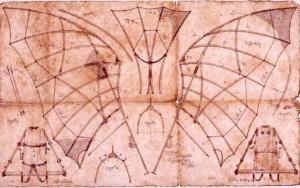

Was Leonardo Da Vinci Innovative?

Let’s tweak it, Leo.

We all know that Leonardo Da Vinci was a genius. But was he innovative?

The question draws a distinction between invention and innovation and between creativity and construction. As Wikipedia puts it, “[Da Vinci] conceptualized a helicopter, a tank, concentrated solar power, an adding machine, and the double hull, also outlining a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics. Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were even feasible during his lifetime….”

In other words, Leonardo had great ideas but many of them were never implemented. So, were they innovations?

That leads to another question: why did Britain lead the way in the Industrial Revolution? Other countries – notably France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden – had great universities and well established scientists and laboratories. Why did Britain create the industrial surge while others followed?

That’s the question that Ralf Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr address in their working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Their short answer: Britain didn’t have more geniuses than other countries, but it did have more tweakers and implementers.

Meisenzahl and Mokyr argue that Britain certainly had its fair share of “hall-of-fame” inventors. But many of those genius ideas would not have been turned into practical innovations if not for “…a group of skilled workmen who possessed the training and natural dexterity to … carry out the ‘instructions’ contained in the … blueprints, … build the parts … with very low degrees of tolerance, and … fill in the blanks when the instructions were inevitably incomplete.”

Meisenzahl and Mokyr try to distinguish between tweakers and implementers. Tweakers “…improved and debugged an existing invention.” Implementers were “…skilled workmen capable of building, installing, operating and maintaining, new and complex equipment.”

Meisenzahl and Mokyr identified 758 men and one woman (Elenor Coade “who invented a new process for making artificial stone…”) whom they could classify as tweakers or implementers. Each person in the database was born between 1660 and 1830. Meisenzahl and Mokyr studied the industries they worked in, what they did, how they were incented, and how they acquired their skills. Among their key findings:

- The apprenticeship system was critical – it produced not only knowledge but also the skill to produce finely tuned machines. It also provided talented youngsters with a stable environment while they acquired and honed their skills.

- Multiple incentives were available. Much has been made of the British patent system in spurring innovation. But the authors argue that a system of prizes was equally or more important. Organizations such as the Society of Arts offered prizes for the development of specific devices, such as a machine to manufacture lace. Many such prizes were awarded “on the condition … that no patent was taken out” – which allowed the innovation to spread more rapidly.

- A “mechanical culture” – the authors point out that, “The second half of the eighteenth century witnessed the maturing of the Baconian program, which postulated that useful knowledge was the key to social improvement. In that culture, technological progress could thrive.”

So Britain not only had its fair share of geniuses but also had a well organized cadre of people who could tweak, improve, and implement the ideas the geniuses handed on. Just think what Leonardo might have done.

Brain Porn

This is your brain on brain porn.

I like to think about our brains. The way the brain functions influences our creativity and communication. These influence our ability to innovate. Innovation influences our business success. It’s all linked together in one continuum, though teasing out how the links actually work is exceedingly difficult.

Since I’m not a neuroscientist by training, I read science-for-the-layperson materials. I enjoy Oliver Sacks, Daniel Kahneman, Peter Facione, Christopher Chabris, Daniel Simons, James Surowiecki, Steven Pinker, and James Gleick to name a few. But I often wonder just how much of what I read is accurate. Is some of it dumbed down for the non-scientist? What can we trust and what should we be suspicious of?

It turns out that there’s a lot of “brain porn” out there. Also known as “folk neuroscience”, this stuff oversimplifies and gives a false sense of certitude. It seems so clear, for instance, that a man who is short on oxytocin will have a rocky romantic life. After all, oxytocin is the “love hormone”. If you don’t have enough, how good a lover can you be?

We humans love to make up stories to explain cause and effect. Some of our stories are even true. In many cases, however, we don’t really know what causes what. It’s complicated. Still, we have a deep-seated need to create backstories that explain why we are the way we are. Neuroscience fits our need perfectly; it appears to give ultimate explanations. We behave a certain way because we’re “hardwired” to do so. We have an imbalance in our brain chemistry and therefore we behave antisocially (or immaturely or irrationally or generously, etc.)

Our desire for an explanation is also a desire for a cure. If an imbalance in our brain chemistry causes antisocial behavior, then all we have to do is learn how to rebalance our brain chemistry. As in A Clockwork Orange, we might turn ultraviolent criminals into well-behaved citizens. All we need to do is understand the brain better and we can make ourselves “better”. A fundamental question is: who gets to define “better”?

So how wrong is brain porn? Vaughan Bell wrote an excellent article in The Guardian that itemizes some basic misunderstandings. For instance, it’s not true that the left-brain is rational and the right-brain creative. We really do need both sides of our brains if we want to be either rational or creative. Similarly, video games don’t “rewire” our brains into some permanently demented state. The brain is constantly changing. Video games may contribute some new connections but so does everything else we do. We can’t get stuck in video game dementia any more than our eyes can get stuck when we cross them.

Despite the brain porn out there, we can still learn a lot about behavior and creativity from neuroscience. In the next few days, for instance, I’ll review an article titled “Your Brain At Work” that really can teach us how to be more effective leaders and managers. I’ll do my best to write about neuroscience that’s well documented and substantiated. I believe there’s a lot of wheat out there. We just need to separate it from the chaff.

Beware The Toy That Destroys

It’s just a toy.

As Clayton Christensen pointed out more than a decade ago, disruptive technologies are often seen as inferior to the technologies they replace. Leading companies can easily dismiss them as toys and ignore them. That’s when the trouble starts.

We’ve seen two examples of this phenomenon in the last week. The first is BlackBerry. Just four years ago, the company had 51% of the North American market for smartphones. Today, it has 3.4%.

There are, of course, many factors behind the decline, but I’d have to guess that the iPhone is the primary disrupter. Here’s how the New York Times describes BlackBerry’s response to the iPhone, “…BlackBerry insiders and executives viewed the iPhone as more of an inferior entertainment device than a credible smartphone, particularly for users in BlackBerry’s base of government and corporate users.”

In other words, BlackBerry dismissed the iPhone as a toy. In fact, long-time readers of this website will remember that BlackBerry actually used the word “toy” in one of its ad campaigns. BlackBerry users, the ad claimed, needed “tools, not toys”. That’s when I concluded that BlackBerry’s future was dismal.

The second example this week is the Washington Post. The Post used to be one of the most influential newspapers in the world. But somehow it missed the Internet wave. I’m guessing that executives at the Post once dismissed the Internet as nothing more than fluff and entertainment. No self-respecting citizen would get serious news and analysis from such a source. It was a toy. It could be ignored.

Now, of course, Jeff Bezos has bought the Post for $250 million. (Critics say he overpaid by a factor of two or three). I admire the Post and I hope that Bezos can help save it. But I can’t imagine how. The Internet has already thoroughly disrupted the Post’s business model.

In an entirely different arena, I see another disruption looming. In higher education, Massively Open Online Courses (MOOCs) threaten to disrupt the genteel world of higher education. Why pay $50,000 a year for a college education when you can get it virtually free on the Internet?

Some leading colleges, of course, are jumping on the MOOC bandwagon and experimenting with different offerings. Other colleges seem to be dismissing MOOCs as inferior “toys”. Just look at what MOOCs don’t offer: a campus, buildings, athletics, football, school spirit, dormitories, etc. But perhaps that’s no longer what customers want. Brick-and-mortar colleges may not crash as fast as BlackBerry did but, if they dismiss MOOCs as toys, their future is just as dismal.

Did The Government Create The iPhone?

Government at its best.

I’ve enjoyed and admired Apple products since I got my first Macintosh in the mid-1980s. Apple products are intuitive; they’re designed for people rather than technologists. I think of the company as innovative and dynamic.

On the other hand, I often hear that our technology and pharmacy companies would be much more innovative if the government would just get out of the way. Critics claim that governments are meddlesome nuisances.

Not so, argues Mariana Mazzucato in her new book, The Entrepreneurial State. A professor at the University of Sussex, Mazzucato documents the government-funded research that enabled many of the great leaps forward in information technology and pharmaceuticals.

Mazzucato argues that the state is the true innovator, willing to invest in high-risk endeavors that can affect all aspects of society. By contrast, private companies are relatively non-innovative; they simply take the results of governmental research and commercialize them. In Mazzucato’s view, the government bears the risk while private companies take the profits.

In an extended example, Mazzucato analyzes Apple’s iPod, iPad, and iPhone and the technologies they incorporate. She identifies a dozen embedded technologies and traces the origin of each. In each case, the technology originated in government (or government-funded) projects.

Mazzucato documents government investments from around the world. For instance, we wouldn’t have the iPod if not for German and French investments in giant magnetoresistance (GMR) that enables tiny disk drives. In the United States, the multi-touch screen was developed at the University of Delaware (my alma mater) with funding from the NSF and the CIA.

Mazzucato argues that we do ourselves a disservice by denigrating governments as bumbling meddlers. Private companies invest for the short-term and are relatively risk averse. Governments can look much farther into the future and can accept much less sanguine risk/reward ratios. As I’ve argued before, governments can create fundamental platforms that many entrepreneurs can capitalize on.

Mazzucato struggles with but doesn’t quite resolve the fundamental issue of fairness. Should Apple pay the government back for all the technologies it has capitalized on? One view is that Apple already reimburses the government through taxes. However, the recent ruckus about Apple’s ability to avoid taxes suggests that the reimbursement may not be full or fair. Perhaps Mazzucato can develop a mechanism that will help reimburse governments adequately for fundamental breakthroughs.

As Mazzucato points out, we tend to tell only half the story. We point to the successes of private industry and the failures of the government. If half the story becomes the whole story, we will underfund government research and drive away talented researchers. We won’t take the big risks but only the incremental, short-term risks that private capital can afford. For all of us who love the iPhone, that would be a shame.

(Click here to watch Professor Mazzucato give a TEDx talk).

Extrinsic, Intrinsic Creativity

I love my work.

When I think about motivating people, I often think about extrinsic factors. What can I do to provide incentives to guide another person’s behavior? This usually involves rewards of one type or another – perhaps money or praise or recognition.

If we want to stimulate creativity, however, Teresa Amabile argues that we need to pay more attention to intrinsic motivation. As Amabile writes, “When people are intrinsically motivated, they engage in their work for the challenge and enjoyment of it. The work itself is motivating.” (Amabile’s article, “How to Kill Creativity” is a classic).

So how do you improve intrinsic motivation? Basically, it’s about leadership, culture, and values. I used to think that intrinsic motivation – being internal – was not subject to external factors. But Amabile’s research leads her to conclude that, “…intrinsic motivation can be increased considerably by even subtle changes in an organization’s environment.” Amabile outlines six factors to consider.

Challenge – this is management’s ability to match the right job to the right person. The ideal job stretches a person but not to the breaking point. To do this successfully, managers need to understand their employees quite well.

Freedom – there are many ways to develop a road map of where we’re going. Whether employees are included in the process is not crucial to creativity. What is crucial is giving employees a lot of latitude in determining how they’re going to get there.

Resources – the big ones are time and money. Setting unrealistic deadlines can derail creativity. (For more about time as a resource, click here). Money can also affect creativity. As Amabile points out, keeping resources too tight, “…pushes people to channel their creativity into finding additional resources, not in actually developing new products or services.” On the other hand, beyond a certain “threshold of sufficiency”, more money doesn’t help.

Work group features – designing a diverse team is critical. If everyone on the team thinks alike, you won’t get creativity. If people from different disciplines collaborate, they may just mash up ideas in very innovative ways. You need diversity, but you also need someone who can help diverse people collaborate – not always an easy task. As Amabile points out, homogenous teams often have high morale but low creativity. Managing morale on a diverse team may be more difficult, but the dividend is creativity.

Supervisory encouragement – we all need encouragement from time to time even if we’re intrinsically motivated by our work. A crucial factor is what happens to a new idea when it’s first proposed. Is it a positive experience? Or is the proposer raked over the coals? Do staff members show how “smart” they are by being critical? Does the idea become a political football? (The concept of Innovation Free Ports addresses this).

Organizational support – individual supervisors can be encouraging, but the entire organization needs to support creativity. This is all about leadership, culture, and values. For instance, information sharing is critical to creativity. If your company culture creates a competitive internal environment where information is hoarded rather than shared, you won’t get creativity. If your culture emphasizes “go along to get along”, you won’t get the diverse ideas that stimulate discussion and creativity (and discord, on occasion).

As you’ve probably guessed, it’s all about people. Take the time to understand people – and their desires and motivations – and you’ll be well rewarded.