Featured

This week’s featured posts.

This week’s featured posts.

Jorge Luis Borges once wrote a story about a unicorn that no one saw. The unicorn grazed widely in the town where it lived and made no effort to hide itself. No one saw the unicorn because no one expected to see a unicorn. We see what we know, Borges seems to say. If we don’t know that something exists, we can’t possibly see it. It’s invisible.

I recently bought a car and decided to get it in flamenco red. I liked the color but I also thought it was unique. I hadn’t seen any flamenco red cars. As soon as I ordered the car, I started seeing flamenco red cars everywhere I looked. I hadn’t seen them before because I didn’t know they existed.

If we only see what we know, we’re going to miss a lot of reality. Worse, we’re going to miss many opportunities to be more creative. If we believe that politicians are liars, then every time we see a newspaper article about a lying politician, we’ll see it and register it. If we see an article about a politician telling the truth, we may just miss it altogether. We didn’t know that such a species existed. We’re missing a chunk of reality and an opportunity to open our minds and see and do things differently.

How do you learn to see what you don’t typically see? Here are some pointers:

As you learn to see more fully, you should also get more creative. You’ll see connections — and opportunities — that you might have missed before. I sometimes wonder if Jorge Luis Borges was so creative precisely because he sees the world so differently. After all, he was blind.

See more in the video.

You’ve told your employees you want more innovation. You’ve sponsored brainstorming sessions. You’ve sponsored mixers to break  down departmental barriers. You’ve offered prizes. You’ve put up motivational posters. You’ve created t-shirts and coffee mugs with all the right slogans.

down departmental barriers. You’ve offered prizes. You’ve put up motivational posters. You’ve created t-shirts and coffee mugs with all the right slogans.

So what do your employees do? They offer up good ideas. Yikes! Now what? If your company is like most, your employees have lots of ideas on how to improve your company, your products, and your services. Give them a little encouragement to open up and share their thoughts, and you’ll get a boatload of suggestions.

What could be wrong with that? Well…. unless you plan ahead, you could create a company full of cynics. Your employees will almost certainly come up with too many ideas. You won’t be able to process them all much less implement them all. As a result, you could easily cause the dreaded Cynical Rebound.

The Cynical Rebound is the natural (and universal) reaction that occurs when one is asked for suggestions and then ignored. You can hear the frustration in phrases like, “If you’re not going to listen to me, then why did you ask my opinion?” “They said they wanted fresh ideas but I guess they didn’t want mine.” “I offered up a good idea and never heard anything. That’s the last time I’ll do that.” If allowed to spread, the Cynical Rebound will bring all of your innovation processes to a screeching halt.

How to avoid the Cynical Rebound? Before you begin an innovation campaign, be sure to set expectations appropriately. Let everyone in the company know that there probably will be too many ideas. You won’t have the bandwidth to pursue all good ideas immediately. You’ll need to stockpile some for future consideration. The keep the communication lines open. One of the major goals of the Innovation Free Port is to communicate the status of good ideas as they wend their way through the process. If an idea is stockpiled, be sure to let everyone know– especially the originator.

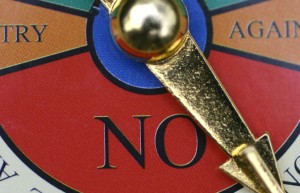

You can also prevent the Cynical Rebound by using the Grateful No. You’ll need to turn down some ideas. Just do it gracefully. The Grateful No starts by separating the person from the idea. The person is wonderful; the idea less so. Express your gratitude to the person and encourage them to continue to offer new ideas. Then explain — clearly and simply — why you’re not going to pursue the idea in the near term. You need to give a real reason; it can’t be fluff. Continue the explanation until you see the person nodding her head. Then stop — you’ve got the sale so quit selling.

The Grateful No closes the loop. The originator knows that you’ve seriously considered the idea but can’t act on it now. She also knows the reason — which could help her formulate better ideas in the future.

Once it gets started, the Cynical Rebound is very hard to stop. So plan ahead. Set expectations appropriately and make sure you have a working Free Port before launching an innovation initiative. Be sure that your managers are trained in the Grateful No technique. A little planning could save you a lot of pain.

If you have a fairly simple product — like soda pop — you can often communicate directly with your market. You figure out who’s likely to buy and craft messages that will appeal to them. Nothing stands between you and your audience. It’s like talking with someone standing nearby on a calm, clear day.

When you have a complicated product or service, on the other hand, you’ll need to deal with an embedded commentariat of current customers, gurus, analysts, pundits, kibbitzers, journalists, and competitors. Each layer of the commentariat can distort your message. It feels like yelling at a person 100 meters away on a windy, foggy, rainy day.

Let’s say you’re introducing a next generation product. You’ll go through an early customer acceptance test to sort out last-minute issues. Once you have everything sorted, you can just put out a press release, right? Wrong.

The issue is that your product is complicated — nobody understands it fully. If your product is very innovative, you have a doubly difficult problem. First, nobody understands it. What does it do? Second, nobody understands its category. What’s it supposed to do? Potential buyers will ask you lots of questions but will then turn to the commentariat to seek verification and validation. So, before you talk to the market, you need to ensure that the commentariat thoroughly understands what you’re doing.

Think of an ice cream cone — it’s wide at the top and narrow at the bottom. The trick with ice cream cone communication is to analyze from the top down but communicate from the bottom up. The top of the cone — the widest part — represents your market. It’s big and broad and tempting. Communicating with the market is your ultimate goal. To get there, you’ll need to work your way through the commentariat.

To organize your communications, work from the top down, with a simple question, “Whom do they trust?” So, who would potential customers trust? It’s a good bet that they would trust the trade press. So take your story to the trade press before you take it to potential customers. Who do the trade press trust? Well, they’ll probably ask to speak to some gurus or analysts who have studied the issue in more detail. So brief the analysts before you take the story to the trade press. Who do the analysts trust? Customers. Analysts want to hear directly from customers, preferably without you in the room. So, prepare your early customers to talk to analysts and then make sure they meet.

And customers — whom do they trust? They’ll talk to many of your employees. Let’s say you’ve told a customer, Angela, that your new product is the best thing since sliced bread. Then Angela talks to John, her favorite consultant on your support line. Angela asks about the hot new product. John says, “I’ve never heard of it”. Unwittingly, John has just undercut the entire communication chain. Angela loses confidence in the product and may even jump to the conclusion that you’re lying.

So always start your communications with your own employees. They’re the narrow, bottom section of the ice cream cone. Make sure they understand the key messages associated with the product. Then work your way upward and outward in the cone, to the interlinked audiences of the commentariat. It will take some time to get to the top of the cone — your target market – but it’s well worth the effort.

The best articles I’ve found in the past week (or so):

True progressivism — an economic agenda that reduces inequality while not stifling growth. A middle way that just might work. From The Economist. Click here.

True progressivism — an economic agenda that reduces inequality while not stifling growth. A middle way that just might work. From The Economist. Click here.

The re-branding of Mitt Romney as Mitt the Moderate in the Financial Times. Click here.

Presenteeism — do people who show up at the office fare better than those who work at home? The Economist says they do. Click here.

Will universities get Amazoned? How online education could wreck the hallowed ivy halls. By Nicholas Carr, the man who wrote “IT Doesn’t Matter”. In Technology Review. Click here.

How Jesus’ wife found her man in The New Yorker — a very funny story. Click here.

I like to read books. Lately, however, it’s making me feel old.

I recently submitted an article to an online magazine that I occasionally write for. I made what I thought was a provocative argument about tall buildings and mental illness. The gist of the argument is that people who live in tall buildings are often isolated from others and become depressed (or worse). The point: get out more often and mix it up with fellow human beings — it’s good for you. I based the argument on research published in 1977 in a book called A Pattern Language which is often described as a classic in the design literature. My son, the architect, recommended it to me. Despite its powerful provenance, my editors rejected the piece because they couldn’t find anything on the Internet to substantiate the argument.

So I went back to my copy of A Pattern Language, scanned the appropriate pages with the relevant citations, and sent them to the editors. They still rejected my article. As they pointed out, 1977 was a long time ago. Things may have changed. If the basis of the argument were still true, it should be somewhere in the Internet.

I’m now wondering what to do with all my old books. Should I toss them out? Are all my old Dave Barry books no longer funny? And Jorge Luis Borges — was he just a ficción of my imagination? I’m just now re-reading A Clockwork Orange — it’s the 50th anniversary. Should I just assume that it’s no dobby chepooka and brosay it into the merzky mesto? Wouldn’t that be horrorshow?

I’ve always wondered, how do we know what we know? Perhaps we can simplify the rules now and say, for something to be known, it must first appear on the Internet. That would simplify our lives — and our education systems. What’s your opinion? When does old information become irrelevant information?

By the way, I re-purposed my original article and published it here.