What Can We Learn From Europe?

Do you think that personal success results mainly from your own hard work or is it due to forces beyond your control? If you’re like 77% of Americans, you believe that success comes from hard work and personal responsibility. That shared belief cuts across all classes. It doesn’t really matter if you’re rich or poor, black or white, Republican or Democrat. No matter how you segment the American population, a majority of most every segment believes that hard work is the key to success.

Do you think that personal success results mainly from your own hard work or is it due to forces beyond your control? If you’re like 77% of Americans, you believe that success comes from hard work and personal responsibility. That shared belief cuts across all classes. It doesn’t really matter if you’re rich or poor, black or white, Republican or Democrat. No matter how you segment the American population, a majority of most every segment believes that hard work is the key to success.

That’s what known as a social contract. We may disagree on lots of hot button issues — gun control, gay marriage, abortion, deficits, etc. — but we fundamentally agree on how to be successful. We may think of ourselves as a fractured body politic but, on some very significant issues, we’re as close to unanimous as a country can be.

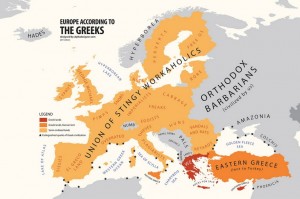

As Lexington points out in a recent column, that’s an important point to keep in mind. It’s also an important difference between America and Europe. When Pew Research asked the same question across Europe, they found a distinct north/south split. Northern Europeans — especially Britons and Germans — agreed that hard work is the key to success. Southern Europeans — especially French, Greeks, and Italians were more fatalistic — success is not because of you but because of the system. In other words, it’s undeserved. By extension, it should be shared with others.

In America, we look to Europe for both positive and negative examples. They’re sort of like us and, therefore, we should be able to learn from their experience. We can debate the merits of the euro or of austerity or of massive bailouts. But Lexington suggests that we’re missing the point. Europeans have fundamentally different world views and, as a result, they just plain don’t like each other. Lexington writes that “…America should fear the spread of the crudest poison paralysing Europe: mutual dislike between citizens.”

It seems so obvious. If we continually demonize each other, then the social contract begins to fray. But that’s exactly what we’re doing. We’re behaving more and more like Europeans. As Lexington puts it, Americans are developing an “ill-concealed contempt for an undeserving other: the feckless poor, the immoral rich …” and concludes: “Mutual dislike is the dirty secret that best explains European paralysis. American politicians have no business stoking it in their far more ambitious union.”

Let’s remember what we do agree on in America. Let’s not balkanize ourselves into another Europe. A little mutual respect would go a long way right about now.

Virtual Prisons

The USA locks up more citizens proportionally than any other country in the world. For every 100,000 people, we have 716 in jail. We’re followed closely by countries like Rwanda (527), Georgia (514), Cuba (510), and Russia (502). Nice company. At the other end of the spectrum we see those pesky Nordic countries again: Denmark (74), Norway (73), Sweden (70), Finland (59), and Iceland (47). (For a list of incarceration rates in 220 countries, click here).

We might think of this as an economic and technical problem. Prisons aren’t very efficient at converting criminals into model citizens. It costs a lot to keep so many people in jail and the recidivism rate is high. This can’t be helping us to balance the budget. So, the question becomes: are there more efficient, less costly ways to keep so many people off the streets?

As Evgeny Morozov points out in a recent article, this is exactly the way the consulting firm, Deloitte, framed the question in its recent report on virtual incarceration. The idea is simple: use technology to increase efficiency. By combining mobile phones with GPS and video cameras, we can lock up low-risk perps in their own homes. It’s less costly and certainly more efficient than current jails. If it can break the role of jails as the higher education centers of crime, it may also be more effective.

But Morozov asks a different question: is that really the problem we want to solve? Wouldn’t it be better to find solutions that would lower the incarceration rate? I’ve written a lot about disruptive innovations (and been the victim of a few), but Morozov writes that, “Smart technologies are not just disruptive; they can also preserve the status quo. Revolutionary in theory, they are often reactionary in practice.” Efficient incarceration is a good example. We’re not changing the fundamentals — we’re just making it easier, cheaper, more efficient to do the same old stuff.

I’ve always been a technical enthusiast. I remember reading Malthus in college. He wrote (in 1798) that, sooner or later, we would run out of resources to support a growing population. Society is improvable only up to a point; it’s certainly not perfectible. I essentially rejected the idea, assuming that technology would always stay a step ahead. If Malthus’ prediction hadn’t come true in 200 years, I thought we could safely ignore it.

Morozov is making a subtler point, however. It’s not just about resources. It’s also about our attitude and our ability to frame questions effectively. As he writes, “That we now have the means to make the most miserable experiences more tolerable should not be an excuse not to reduce the misery of those experiences.”

I think an increasing number of Americans is growing increasingly concerned about the number of people we lock up. We may be building a consensus for change. If we make incarceration less costly and more efficient, we may just undercut that consensus. Is that really what we want?

If Morozov is right, we may have to re-phrase Karl Marx’s classic aphorism. Reigion isn’t the opium of the people. Technology is.

(By the way, Morozov has also written a terrific book, To Save Everything Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism, which I’ll write about soon).

My Strategic Pause

It’s true. Every now and then, I get annoyed. I have a fairly long fuse but, when I get to the end of it, I become agitated, irritable, snarky, and overbearing.

It’s true. Every now and then, I get annoyed. I have a fairly long fuse but, when I get to the end of it, I become agitated, irritable, snarky, and overbearing.

I find that about half the time when I get to that stage, it’s because something external to me got me there. Another person gets my goat. Someone else screws up and I’m left holding the bag. A mechanical failure delays yet another flight and, no, I can’t get home tonight. As the saying goes, if it’s not one thing, it’s your mother.

If external factors cause about half of my annoyance attacks, where do the other half come from? Well …. from me. How do I know this? Because I keep track of my flaming e-mails. I live a lot of my life online. I process roughly 100 to 150 e-mails per day.

When I’m annoyed, I sometimes send flaming e-mails. It just feels good to send a self-righteous missive excoriating the recipient for innate stupidity. “Were you born stupid or is this a recent development?” About half the time, my analysis is correct (though my tactics are self-defeating). The other half of the time, I ultimately find out that my own stupidity caused the problem. I failed to check a box, or fill in a blank, or submit the paperwork on time and, therefore, it’s my fault. Then I really feel stupid.

So now when I get to the end of my rope, I take a strategic pause. That’s a fancy term that comes from the critical thinking world but it’s a technique that we all learned in grade school: count to ten before you start throwing fists.

Actually, I do more than count to ten. Here’s a summary of my thinking:

“OK, I’m really annoyed. I know that when I’m annoyed, I don’t always think clearly. I also know that about half the time when I’m annoyed, it’s my own damn fault. So, how am I going to figure out: a) who or what caused this annoyance; b) what I’m going to do about it? I might need some facts here.”

Then I turn to my “go-to” questions. I call them “go-to” questions because I’ve used them often enough that they’re always with me. I may forget the rules of logic, but I can always go to these questions. There are four of them. The first two are for me. I use the last two only after considering the first two and only if there is another person involved in the annoyance incident.

The first two are simply:

- How do I know that?

- Why do I think that?

By asking these two questions, I can go back to the beginning, recount the process that got me to where I got to, and decide whether I’m on firm ground or not. If not, I can start to make corrections. If I am on firm ground, I can ask the next two questions (of the other person):

- How do you know that?

- Why do you think that?

These questions have helped me avoid countless misunderstandings. I might say, “Why do you think that?” The other person might say, “Because you said XYZ.” I might then say, “Actually, I didn’t say XYZ. I said ZYX.” Rather than shooting first and asking questions later, we can ask questions and perhaps avoid shooting altogether. It’s a simple approach that often stops an argument before it comes to a boil.

I’ve developed my go-to questions based on years of experience. I always advise my critical thinking students to develop their own go-to questions. In class, we often discuss which questions are most effective in a strategic pause. So, now you can help me teach my class. What are your most effective go-to questions?

How Many Intelligences Do You Need?

When driving home from a party, I may ask Suellen a question like, “Why did Pat make that cutting remark about Kim?” Suellen will then launch into a thorough exegesis about relationships, personal histories, boyfriends, girlfriends, children, parents, gardening, the nature of education, and the tangled web we weave when first we practice to deceive. In the end, it will all make sense — even to me, a socially challenged kind of guy.

Suellen is great at answering questions like these. It’s often referred to as social or emotional intelligence. It’s about people and relationships and empathy. I’m generally better at academic intelligence and questions like how do you calculate the volume of a sphere? (I don’t mean to say that I’m better at academic intelligence than Suellen is … but that I’m better at academic intelligence than I am at social intelligence. I hope that’s clear… I wouldn’t want my lack of social intelligence to lead me to insult my own wife.)

For me, two intelligences — academic and social — have been quite enough. But not for Howard Gardner. In Five Minds for the Future, Gardner suggests that there are five different intelligences and, if education is to succeed in the future, we need to teach them all.

I’m fairly well versed in the tenets of critical thinking. Now I’m trying to understand Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. Why? Because I’d like to mash up critical thinking and multiple intelligences. I’m wondering if critical thinking works the same way in each intelligence. Can you think critically in say, academic intelligence, while thinking uncritically in social intelligence? That’s certainly the stereotype of the absent-midned professor.

To mash up critical thinking and the five minds, let’s first look at Gardner’s theory. The five minds are:

Disciplined mind — to master the way of thinking associated with a specific discipline — say, economics, psychology, or mathematics. I think (hope) it’s also broader than that. I’m certainly trained in the Western way of thinking. I categorize and classify things without even thinking about it. I’m now looking at Zen as a different way of thinking — one that destroys categories rather than creates them. That’s certainly a different discipline.

Synthesizing mind — the ability to put it altogether. Gardner points out that memorization was important in times characterized by low literacy. In today’s era of Big Data, synthesis is much more important and memorization much less important.

Creating mind — proposing new ideas, fresh questions, unexpected answers. As I’ve noted before in this blog, a new idea is often a mashup of multiple existing ideas. To propose something that doesn’t exist, you need to be well versed in what does exist.

Respectful mind — “… notes and welcomes differences between human individuals and between human groups….” This is very similar to the concept of fair mindedness as used in critical thinking. This could be our first mashup.

Ethical mind — how can we serve purposes beyond self-interest and how can “citizens…work unselfishly to improve the lot of all.” Again, this is quite similar to concepts used in critical thinking, including ethical thinking and the ability to overcome egocentric thinking.

Today, I simply want to introduce Gardner’s five minds. In future posts, I’ll try to weave together critical thinking, Gardner’s concepts of multiple intelligences, and the Hofstedes’ research on the five dimensions of culture. I hope you’ll tag along.

By the way, the volume of a sphere in 4/3∏r³.

How Do You Know If Something Is True?

I used to teach research methods. Now I teach critical thinking. Research is about creating knowledge. Critical thinking is about assessing knowledge. In research methods, the goal is to create well-designed studies that allow us to determine whether something is true or not. A well-designed study, even if it finds that something is not true, adds to our knowledge. A poorly designed study adds nothing. The emphasis is on design.

I used to teach research methods. Now I teach critical thinking. Research is about creating knowledge. Critical thinking is about assessing knowledge. In research methods, the goal is to create well-designed studies that allow us to determine whether something is true or not. A well-designed study, even if it finds that something is not true, adds to our knowledge. A poorly designed study adds nothing. The emphasis is on design.

In critical thinking, the emphasis is on assessment. We seek to sort out what is true, not true, or not proven in our info-sphere. To succeed, we need to understand research design. We also need to understand the logic of critical thinking — a stepwise progression through which we can discover fallacies and biases and self-serving arguments. It takes time. In fact, the first rule I teach is “Slow down. Take your time. Ask questions. Don’t jump to conclusions.”

In both research and critical thinking, a key question is: how do we know if something is true? Further, how do we know if we’re being fair minded and objective in making such an assessment? We discuss levels of evidence that are independent of our subjective experience. Over the years, thinkers have used a number of different schemes to categorize evidence and evaluate its quality. Today, the research world seems to be coalescing around a classification of evidence that has been evolving since the early 1990s as part of the movement toward evidence-based medicine (EBM).

The classification scheme (typically) has four levels, with 4 being the weakest and 1 being the strongest. From weakest to strongest, here they are:

- 4 — evidence from a panel of experts. There are certain rules about such panels, the most important of which is that it consists of more than one person. Category IV may also contain what are known as observational studies without controls.

- 3 — evidence from case studies, observed correlations, and comparative studies. (It’s interesting to me that many of our business schools build their curricula around case studies — fairly weak evidence. I wonder if you can’t find a case to prove almost any point.)

- 2 — quasi-experiments — well-designed but non-randomized controlled trials. You manipulate the independent variable in at least two groups (control and experimental). That’s a good step forward. Since subjects are not randomly assigned, however, a hidden variable could be the cause of any differences found — rather than the independent variable.

- 1b — experiments — controlled trials with randomly assigned subjects. Random assignment isolates the independent variable. Any effects found must be caused by the independent variable. This is the minimum proof of cause and effect.

- 1a — meta-analysis of experiments. Meta-analysis is simply research on research. Let’s say that researchers in your field have conducted thousands of experiments on the effects of using electronic calculators to teach arithmetic to primary school students. Each experiment is data point in a meta-analysis. You categorize all the studies and find that an overwhelming majority showed positive effects. This is the most powerful argument for cause-and-effect.

You might keep this guide in mind as you read your daily newspaper. Much of the “evidence” that’s presented in the media today doesn’t even reach the minimum standards of Level 4. It’s simply opinion. Stating opinions is fine, as long as we understand that they don’t qualify as credible evidence.