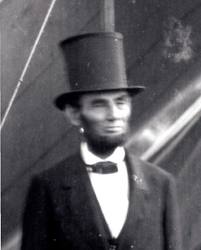

Little Life Lessons from Lincoln

On July 4, 1863, Robert E. Lee was leading a Confederate army in retreat from Gettysburg when they were trapped against the rain-swollen Potomac River. The Union army, commanded by General George Meade, pursued the rebels. Abraham Lincoln ordered Meade to attack immediately. Instead, Meade dithered, the weather cleared, the river shrank, and Lee and his army escaped. Lincoln was furious and penned this letter to Meade:

I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within our easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely. If you could not safely attack Lee last Monday, how can you possibly do so south of the river, when you can take with you very few— no more than two-thirds of the force you then had in hand? It would be unreasonable to expect and I do not expect that you can now effect much. Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.

Interestingly, Lincoln never sent the letter — it was found among his papers after his death. Lincoln generally praised his colleagues for their positive accomplishments and said little or nothing about their failures. Apparently, he wrote letters like the one to Meade to relieve his own frustrations — and perhaps to leave a record for history — rather than to humiliate his colleagues and create public acrimony.

As Douglas Wilson, a Lincoln scholar, pointed out in a recent article (click here), Lincoln was great communicator but not necessarily in the way we think. Some tidbits on how he worked:

- He rarely spoke in public and when he did he was very well prepared. We think of the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural speech as great feats of oratory — and they were. But there weren’t many such feats; he gave relatively few speeches. And he almost never spoke off the cuff. He knew that people followed his words closely and he prepared meticulously. His speeches were extraordinary. Equally extraordinary is the fact that he almost never said anything stupid that he had to retract. Our politicians and executives today could learn a lot from him.

- He pre-wrote his speeches. Lincoln always had scraps of paper with him — which he often stored in his hat. When an idea — or an elegant way to phrase an idea — came to him, he jotted it down. He didn’t start thinking about his speeches when a deadline drew near. He was thinking about them virtually all the time.

- He was mercifully brief. The Gettysburg Address consisted of 267 words. By contrast, this post has about 600. Which one do you think will live longer?

- He cultivated the press before he needed them. In general, Lincoln got to know his audience before he spoke to them. He gave favors to journalists before he asked for favors in return. Getting to know your audience and letting them know that you genuinely care about them are always good strategies.

- He understood event jujitsu. The Civil War began with the crisis at Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. Lincoln could have sent in a fleet to shoot up the Confederate fortifications. Instead, he sent in a small re-supply mission. When the Confederates sought to block the mission, they fired the first shots of the war. It’s a small leap to conclude that the Confederates “started” the war. Thus, a small incident became a major victory in the battle to shape perceptions.

Lincoln has always been one of my favorite presidents and I certainly enjoyed the recent movie from Steven Spielberg. Lincoln communicated effectively and was an expert at shaping public opinion. As the movie showed, he was also adept at cutting deals and rolling logs to achieve his greater goals. Not bad for a kid from the prairies.

Where Does Credibility Come From?

According to the Greeks, a persuasive presentation consists of three major elements:

- Ethos (trust) — first you need to establish that you are a trustworthy person. (Click here for more).

- Logos (logic) — once you’re perceived as trustworthy (and only then), you can deliver the logic of your argument. (Click here).

- Pathos (emotion) — to sum up, you need to touch on the audience’s emotions. Why is your recommendation good for them? (Click here).

I’ve always wondered, how do you quickly establish that you’re a trustworthy person? It’s not easy to project trustworthiness to an audience. Credibility is certainly a key ingredient — but that just begs the question, how do you project credibility?

Then I re-read Jay Conger’s article (click here) and discovered that credibility comes from two sources: experience and relationships.

I intuitively understood the experience part. Whenever I speak to an audience, I briefly introduce the relevant details of my experience. I try not to overdo it as I don’t want to come across as arrogant or academic. I find that a little self-deprecation can help. This is typically a variant on, “I know a lot about the topic because I’ve made a lot of mistakes….” Ultimately, however, I want the audience to know that I have been successful. To do this, I often find it helpful to have someone else introduce me. They can brag about me in ways that I can’t.

Conger points out that credibility also includes open-mindedness. Persuasive people are often perceived as good listeners as well as good speakers. They can incorporate what their audience has to say and adjust their positions. This is the relationship aspect of credibility. People who are honest, even-keeled, and who “generously share credit” are perceived as more credible and trustworthy.

But what if your audience doesn’t know that you are honest, even-keeled, and appreciative? What if you’re speaking to the audience for the first time? I find it’s very useful to interview members of the audience before I give a presentation. Then I can discuss my experiences and what I’ve learned. I’m more credible simply because I listened before speaking.

I also like to speak to the audience’s customers before a presentation. Because I’m an outsider, I can ask “dumb” questions of customers. This often produces interesting, even unique, insights that I can pass on to the audience. That demonstrates that I’m open to interesting sources of information and that I have some interesting perspectives to share. That makes me more credible and more persuasive.

Before you approach an audience, think about how you’ll build your credibility and trustworthiness. If you establish that you’re trustworthy early in the presentation, you may well succeed. If you can’t establish your credibility, the rest of your presentation is just wasted time.

Winning vs. Winning & Losing

How is winning an argument different from winning a baseball game? In baseball, you have a winner and a loser. In an argument, you need more than just good communication skills — if you’re smart — you can have two winners. It all depends on how you play the game after you’ve “won”. Being a good winner this time will make you even more persuasive next time. Learn more in the video.

Disagreeing Effectively

Let’s say you’re having an argument and your opponent has stated his position clearly. You’d like to persuade him to change his position. But you’re working against the consistency principle — once your opponent has stated a position, inertia keeps him from changing it. Your argument needs to be clear and compelling but it also needs to provide a way for your opponent to change positions gracefully. While it may be tempting, making your opponent feel small or cornered is usually unsuccessful. Remember, you’re interested in persuading, not humiliating. Similarly, making your argument overly abstract doesn’t do much good. You need to get personal and stay positive. Learn more in the video.

This tip has a lot to do with the consistency principle — and how to overcome it. You can find more on the consistency principle here.