Tongue-tied On Valentine’s Day?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

Valentine’s cards intrigue me. Suellen and I exchange them every year. Some are sweet. Some are funny. Some are silly. Some are mildly sexy. But really, is there anything new in them? Have we come a long way, baby, or are we just recycling platitudes? And how did people in past centuries address their love, passion, and heartaches? What can we learn from our ancestors?

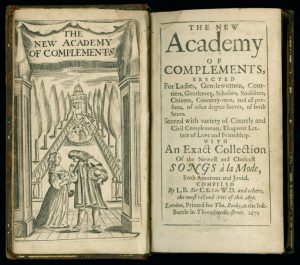

By happy accident, I discovered a partial answer in the Newberry Library in Chicago. The Newberry holds a copy of The New Academy of Complements published in London in the 17th century. The small book – easily tucked in a pocket — is addressed to “both Sexes” and contains a “variety of Courtly and Civil complements” as well as “Eloquent Letters of Love and Friendship … both amorous and jovial.” Happily, the compliments are compiled by “the most refined Wits of the Age.”

What were the best amorous compliments of 17thcentury England? Here are a few of my favorite selections. *

Complemental Expressions towards Men, Leading to The Art of Courtship.

Sir, Your Goodness is as boundless, as my desires to serve you.

Sir, You are so highly generous, that I am altogether senceless.

Sir, You are so noble in all respects that I have learn’d to love, as well as to admire you.

Sir, Your Vertues are so well known, you cannot think I flatter.

Complements towards Ladies, Gentlewomen, Maids, &c.

Madam, When I see you I am in paradice, it is then that my eyes carve me out a feast of Love.

Madam, Your beauty hath so bereav’d me of my fear, that I do account it far more possible to die, than to forget you.

Madam, Since I want merits to equallize your Vertues, I will for ever mourn for my imperfections.

Madam, You are the Queen of Beauties, your vertues give a commanding power to every mortal.

Madam, Had I a hundred hearts I should want room to entertain your love.

I don’t have room to quote many of the gems contained in the book, but here are a few of the categories. Each category provides several models of what to say or write to address the situation. Who knows – you might need one from time to time.

A Gentleman of good Birth, but small Fortune, to a worthy Lady, after she had given a denial.

The Ingratiating Gentleman to his angry Mistriss.

The Lover to his Mistriss, upon his fear of her entertaining a new Servant.

The Jealous Lover to his beloved. The Answer: A Lady to her Jealous Lover.

A crack’t Virgin to her deceitful Friend, who hath forsook her for the love of a Strumpet.

A Lover to his Mistriss, who had lately entertained another Servant to her bosom, and her bed. The Answer: The Lady to her Lover, in defence of her own Innocency.

As you can see, The Academy provides the words to address (and perhaps remedy) most any situation. Is a bald man bothering you? Here’s how to respond:

Sir…while I could be content to keep my Coaches, my Pages, Lackeys, and Maids, I confess I could never endure the society of a bald pate.

I think the Newberry might find an interesting niche market by publishing high quality Valentine’s cards with extracts from The Academy. I know I would buy some. In the meantime, I hope you can find an appropriate quote for whatever your needs are this Valentine’s Day

* The edition held by the Newberry Library was published in 1671. The selections in this article are drawn from the 1669 edition

Will AI Be The End Of Men?

A little over two years ago, I wrote an article called Male Chauvinist Machines. At the time, men outnumbered women in artificial intelligence development roles by about eight to one. A more recent report suggests the ratio is now about three to one.

The problem is not just that men outnumber women. Data mining also presents an issue. If machines mine data from the past (what other data is there?), they may well learn to mimic biases from the past. Amazon, for instance, recently found that its AI recruiting system was biased against women. The system mined data from previous hires and learned that resumés with the word “woman” or “women” were less likely to be selected. Assuming that this was the “correct” decision, the system replicated it.

Might men create artificial intelligence systems that encode and perpetuate male chauvinism? It’s possible. It’s also possible that the emergence of AI will mean the “end of men” in high skill, cognitively demanding jobs.

That’s the upshot of a working paper recently published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) titled, “The ‘End of Men’ and Rise of Women In The High-Skilled Labor Market”.

The paper documents a shift in hiring in the United States since 1980. During that time the probability that a college-educated man would be employed in a

“… cognitive/high wage occupation has fallen. This contrasts starkly with the experience for college-educated women: their probability of working in these occupations rose.”

The shift is not because all the newly created high salary, cognitively demanding jobs are in traditionally female industries. Rather, the shift is “….accounted for by a disproportionate increase in the female share of employment in essentially all good jobs.” There seems to be a pronounced female bias in hiring for cognitive/high wage positions — also known as “good jobs”.

Why would that be? The researchers consider that “…women have a comparative advantage in tasks requiring social and interpersonal skills….” So, if industry is hiring more women into cognitive/high-wage jobs, it may indicate that such jobs are increasingly requiring social skills, not solely technical skills. The researchers specifically state that:

“… our hypothesis is that the importance of social skills has become greater within high-wage/cognitive occupations relative to other occupations and that this … increase[s] the demand for women relative to men in good jobs.”

The authors then present 61 pages on hiring trends, shifting skills, job content requirements, and so on. Let’s just assume for a moment that the authors are correct – that there is indeed a fundamental shift in the good jobs market and an increasing demand for social and interpersonal skills. What does that bode for the future?

We might want to differentiate here between “hard skills” and “soft skills” – the difference, say, between physics and sociology. The job market perceives men to be better at hard skills and women to be better at soft skills. Whether these differences are real or merely perceived is a worthy debate – but the impact on industry hiring patterns is hard to miss.

How will artificial intelligence affect the content of high-wage/cognitive occupations? It’s a fair bet that AI systems will displace hard skills long before they touch soft skills. AI can consume data and detect patterns far more skillfully than humans can. Any process that is algorithmic – including disease diagnosis – is subject to AI displacement. On the other hand, AI is not so good at empathy and emotional support.

If AI is better at hard skills than soft skills, then it will disproportionately displace men in good jobs. Women, by comparison, should find increased demand (proportionately and absolutely) for their skills. This doesn’t prove that the future is female. But the future of good jobs may be.

It’s Social Science. We’re Screwed.

What’s harder: physics or sociology?

We tend to lionize physicists. They’re the people who send spacecraft to faraway places, search for extraterrestrial life, and create modern wonders like virtual reality goggles. In short, many of us have physics envy.

On the other hand, we tend to make fun of sociologists. What they’re doing seems to be nothing more than fancified common sense. I once heard a derisive definition of a sociologist: “He’s the guy who needs a $100K federal grant just to find the local bookie.” Few of us have sociology envy.

But is physics really harder than sociology? I thought about this question as I listened to an episode of 99% Invisible, one of my favorite podcasts. The episode, titled “Built to Burn” is all about forest fires and how we respond to them.

We take a fairly simple approach to forest fires: we try to put them out. But this leads to unintended consequences. If we successfully fight fires, the forest becomes thicker. The next fire becomes more intense and more difficult to stop. As one forest ranger puts it: “A fire put out is a fire put off.”

A general question is: Why do we need to put out forest fires? The specific answer is that we need to protect homes and properties and buildings. We assume that we have to stop the fire to protect the property.

But do we? Enter Jack Cohen, a research scientist for the Forest Service. Cohen has studied forest fires intensively. He has even set a few of his own. His conclusion: we can separate the idea of stopping wildfires from the goal of protecting property.

Cohen’s basic idea is a home ignition zone that stretches about 100 feet in all directions around a house. By spacing trees, planting fire resistant crops, and modifying the home itself (no wood roofs), we can protect homes while letting nature takes its course. We no longer have to risk lives and spend millions if our goal is to protect homes.

Cohen has done the hard scientific work. So, can we assume that his ideas have caught on like … um, wildfire? Not so fast. People seem to understand the science but are still reluctant to change their behavior.

Cohen relates a conversation with a friend about the difference between fighting fires and saving homes. It goes something like this:

Friend: “Modifying homes to make them fire resistant isn’t rocket science.”

Cohen: “No. This is much harder. This is social science.”

Friend: “Oh, jeez. We’re screwed.”

Cohen has done the hard science but the hard work remains. As Albert Einstein, the most famous physicist of all, said: “It’s easier to smash an atom than a prejudice.” Perhaps it’s time to develop some sociology envy.

Critical Thinking — Ripped From The Headlines!

Daniel Kahneman, the psychologist who won the Nobel prize in economics, reminds us that, “What you see is not all there is.” I thought about Kahneman when I saw the videos and coverage of the teenagers wearing MAGA hats surrounding, and apparently mocking, a Native American activist who was singing a tribal song during a march in Washington, D.C.

The media coverage essentially came in two waves. The first wave concluded that the teenagers were mocking, harassing, and threatening the activist. Here are some headlines from the first wave:

ABC News: “Viral video of Catholic school teens in ‘MAGA’ caps taunting Native Americans draws widespread condemnation; prompts a school investigation.”

Time Magazine: “Kentucky Teens Wearing ‘MAGA’ Hats Taunt Indigenous Peoples March Participants In Viral Video.”

Evening Standard (UK): “Outrage as teens in MAGA hats ‘mock’ Native American Vietnam War veteran.”

The second media wave provided a more nuanced view. Here are some more recent headlines:

New York Times: “Fuller Picture Emerges of Viral Video of Native American Man and Catholic Students.”

The Guardian (UK): “New video sheds more light on students’ confrontation with Native American.”

The Stranger: “I Thought the MAGA Boys Were S**t-Eating Monsters. Then I Watched the Full Video.”

So, who is right and who is wrong? I’m not sure that we can draw any certain conclusions. I certainly do have some opinions but they are all based on very short video clips that are taken out of context.

What lessons can we draw from this? Here are a few:

- Reality is complicated and — even in the best circumstances — we only see a piece of it.

- We see what we expect to see. Tell me how you voted, and I can guess what you saw.

- It’s very hard to draw firm conclusions from a brief slice-of-time sources such as a photograph or a video clip. The Atlantic magazine has an in-depth story about how this story evolved. One key sentence: “Photos by definition capture instants of time, and remove them from the surrounding flow.”

- There’s an old saying that “Journalism is the first draft of history”. Photojournalism is probably the first draft of the first draft. It’s often useful to wait to see how the story evolves. Slowing down a decision process usually results in a better decision.

- It’s hard to read motives from a picture.

- Remember that what we see is not all there is. As the Heath brothers write in their book, Decisive, move your spotlight around to avoid narrow framing.

- Humans don’t like to be uncertain. We like to connect the dots and explain things even when we don’t have all the facts. But, sometimes, uncertainty is the best we can hope for. When you’re uncertain, remember the lessons of Appreciative Inquiry and don’t default to the negative.

False Consensus and Preference Falsification

The Soviet Union collapsed on December 26, 1991. While signs of decay had been growing, the final collapse happened with unexpected speed. The union disappeared almost overnight and surprisingly few Soviet citizens bothered to defend it. Though it had seemed stable – and persistent – even a few months earlier, it evaporated with barely a whimper.

We could (and probably will) debate for years why the USSR disappeared, I suspect that two cognitive biases — false consensus and preference falsification — were significant contributors. Simply put, many people lied. They said that they supported the regime when, in fact, they did not. When they looked to others for their opinions, those people also lied about their preferences. It seemed that people widely supported the government. They said so, didn’t they? Since a majority seemed to agree, it was reasonable to assume that the government would endure. Best to go with the flow. But when cracks in the edifice appeared, they quickly brought down the entire structure.

Why would people lie about their preferences? Partially because they believed that a consensus existed in the broader community. In such situations, one might lie because of:

- A desire to stay in step with majority opinion — this is essentially a sociocentric bias. We enhance our self-esteem by agreeing with the majority.

- A desire to remain politically correct – this may be fear-induced, especially in authoritarian regimes.

- Lack of information – when information is scarce, we may assume that the majority (as we perceive it) is probably right. We should go along.

False consensus and preference falsification can lead to illogical outcomes such as the Abilene paradox. Nobody wanted to go to Abilene but each person thought that everybody else wanted to go to Abilene … so they all went. A false consensus existed and everybody played along.

We can also see this happening with the risky shift. Groups tend to make riskier decisions than individuals. Why? Oftentimes, it’s because of a false consensus. Each member of the group assumes that other members of the group favor the riskier strategy. Nobody wants to be seen as a wimp, so each member agrees. The decision is settled – everybody wants to do it. This is especially problematic in cultures that emphasize teamwork.

Reinhold Niebuhr may have originated this stream of thought in his book Moral Man and Immoral Society, originally published in 1932. Niebuhr argued that individual morality and social morality were incompatible. We make individual decisions based on our moral understanding. We make collective decisions based on our understanding of what society wants, needs, and demands. More succinctly, “Reason is not the sole basis of moral virtue in men. His social impulses are more deeply rooted than his rational life.”

In 1997, the economist, Timur Kuran, updated this thinking with his book, Private Truths, Public Lies. While Niebuhr focused on the origins of such behavior, Kuran focused more attention on the outcomes. He notes that preference falsification helps preserve “widely disliked structures” and provides an “aura of stability on structures vulnerable to sudden collapse.” Further, “When the support of a policy, tradition, or regime is largely contrived, a minor event may activate a bandwagon that generates massive yet unanticipated change.”

How can we mitigate the effects of such falsification? Like other cognitive biases, I doubt that we can eliminate the bias itself. As Lady Gaga sings, we were born this way. The best we can do is to be aware of the bias and question our decisions, especially when our individual (private) preferences differ from the (perceived) preferences of the group. When someone says, “Let’s go to Abilene” we can ask, “Really? Does anybody really want to go to Abilene?” We might be surprised at the answer.