How Many Cognitive Biases Are There?

In my critical thinking class, we begin by studying 17 cognitive biases that are drawn from Peter Facione’s excellent textbook, Think Critically. (I’ve also summarized these here, here, here, and here). I like the way Facione organizes and describes the major biases. His work is very teachable. And 17 is a manageable number of biases to teach and discuss.

While the 17 biases provide a good introduction to the topic, there are more biases that we need to be aware of. For instance, there’s the survivorship bias. Then there’s swimmer’s body fallacy. And the Ikea effect. And the self-herding bias. And don’t forget the fallacy fallacy. How many biases are there in total? Well, it depends on who’s counting and how many hairs we’d like to split. One author says there are 25. Another suggests that there are 53. Whatever the precise number, there are enough cognitive biases that leading consulting firms like McKinsey now have “debiasing” practices to help their clients make better decisions.

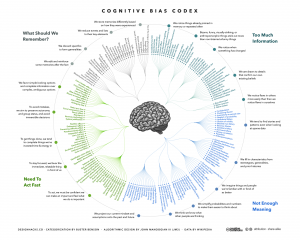

The ultimate list of cognitive biases probably comes from Wikipedia, which identifies 104 biases. (Click here and here). Frankly, I think Wikipedia is splitting hairs. But I do like the way Wikipedia organizes the various biases into four major categories. The categorization helps us think about how biases arise and, therefore, how we might overcome them. The four categories are:

1) Biases that arise from too much information – examples include: We notice things already primed in memory. We notice (and remember) vivid or bizarre events. We notice (and attend to) details that confirm our beliefs.

2) Not enough meaning – examples include: We fill in blanks from stereotypes and prior experience. We conclude that things that we’re familiar with are better in some regard than things we’re not familiar with. We calculate risk based on what we remember (and we remember vivid or bizarre events).

3) How we remember – examples include: We reduce events (and memories of events) to the key elements. We edit memories after the fact. We conflate memories that happened at similar times even though in different places or that happened in the same place even though at different times, … or with the same people, etc.

4) The need to act fast – examples include: We favor simple options with more complete information over more complex options with less complete information. Inertia – if we’ve started something, we continue to pursue it rather than changing to a different option.

It’s hard to keep 17 things in mind, much less 104. But we can keep four things in mind. I find that these four categories are useful because, as I make decisions, I can ask myself simple questions, like: “Hmmm, am I suffering from too much information or not enough meaning?” I can remember these categories and carry them with me. The result is often a better decision.

Business School And The Swimmer’s Body Fallacy

He’s tall because he plays basketball.

Michael Phelps is a swimmer. He has a great body. Ian Thorpe is a swimmer. He has a great body. Missy Franklin is a swimmer. She has a great body.

If you look at enough swimmers, you might conclude that swimming produces great bodies. If you want to develop a great body, you might decide to take up swimming. After all, great swimmers develop great bodies.

Swimming might help you tone up and trim down. But you would also be committing a logical fallacy. Known as the swimmer’s body fallacy, it confuses selection criteria with results.

We may think that swimming produces great bodies. But, in fact, it’s more likely that great bodies produce top swimmers. People with great bodies for swimming – like Ian Thorpe’s size 17 feet – are selected for competitive swimming programs. Once again, we’re confusing cause and effect. (Click here for a good background article on swimmer’s body fallacy).

Here’s another way to look at it. We all know that basketball players are tall. But would you accept the proposition that playing basketball makes you tall? Probably not. Height is not malleable. People grow to a given height because of genetics and diet, not because of the sports they play.

When we discuss height and basketball, the relationship is obvious. Tallness is a selection criterion for entering basketball. It’s not the result of playing basketball. But in other areas, it’s more difficult to disentangle selection factors from results. Take business school, for instance.

In fact, let’s take Harvard Business School or HBS. We know that graduates of HBS are often highly successful in the worlds of business, commerce, and politics. Is that success due to selection criteria or to the added value of HBS’s educational program?

HBS is well known for pioneering the case study method of business education. Students look at successful (and unsuccessful) businesses and try to ferret out the causes. Yet we know that, in evidence-based medicine, case studies are considered to be very weak evidence.

According to medical researchers, a case study is Level 3 evidence on a scale of 1 to 4, where 4 is the weakest. Why is it so weak? Partially because it’s a sample of one.

It’s also because of the survivorship bias. Let’s say that Company A has implemented processes X, Y, and Z and been wildly successful. We might infer that practices X, Y, and Z caused the success. Yet there are probably dozens of other companies that also implemented processes X, Y, and Z and weren’t so successful. Those companies, however, didn’t “survive” the process of being selected for a B-school case study. We don’t account for them in our reasoning.

(The survivorship bias is sometimes known as the LeBron James fallacy. Just because you train like LeBron James doesn’t mean that you’ll play like him).

So we have some reasons to suspect the logical underpinnings of a case-base education method. So, let’s revisit the question: Is the success of HBS graduates due to selection criteria or to the results of the HBS educational program? HBS is filled with brilliant professors who conduct great research and write insightful papers and books. They should have some impact on students, even if they use weak evidence in their curriculum. Shouldn’t they? Being a teacher, I certainly hope so. If so, then the success of HBS graduates is at least partially a result of the educational program, not just the selection criteria.

But I wonder …