What We Don’t Know and Don’t See

It’s hard to think critically when you don’t know what you’re missing. As we think about improving our thinking, we need to account for two things that are so subtle that we don’t fully recognize them:

- Assumptions – we make so many assumptions about the world around us that we can’t possibly keep track of them all. We make assumptions about the way the world works, about who we are and how we fit, and about the right way to do things (the way we’ve always done them). A key tenet of critical thinking is that we should question our own thinking. But it’s hard to question our assumptions if we don’t even realize that we’re making assumptions.

- Sensory filters – our eye is bombarded with millions of images each second. But our brain can only process roughly a dozen images per second. We filter out everything else. We filter out enormous amounts of visual data, but we also filter information that comes through our other senses – sounds, smells, etc. In other words, we’re not getting a complete picture. How can we think critically when we don’t know what we’re not seeing? Additionally, my picture of reality differs from your picture of reality (or anyone else’s for that matter). How can we communicate effectively when we don’t have the same pictures in our heads?

Because of assumptions and filters, we often talk past each other. The world is a confusing place and becomes even more confusing when our perception of what’s “out there” is unique. How can we overcome these effects? We need to consider two sets of questions:

- How can we identify the assumptions were making? – I find that the best method is to compare notes with other people, especially people who differ from me in some way. Perhaps they work in a different industry or come from a different country or belong to a different political party. As we discuss what we perceive, we can start to see our own assumptions. Additionally we can think about our assumptions that have changed over time. Why did we used to assume X but now assume Y? How did we arrive at X in the first place? What’s changed to move us toward Y? Did external reality change or did we change?

- How can we identify what we’re not seeing (or hearing, etc.)? – This is a hard problem to solve. We’ve learned to filter information over our entire lifetimes. We don’t know what we don’t see. Here are two suggestions:

- Make the effort to see something new – let’s say that you drive the same route to work every day. Tomorrow, when you drive the route, make an effort to see something that you’ve never seen before. What is it? Why do you think you missed it before? Does the thing you missed belong to a category? Are you missing the entire category? Here’s an example: I tend not to see houseplants. My wife tends not to see classic cars. Go figure.

- View a scene with a friend or loved one. Write down what you see. Ask the other person to do the same. What are the differences? Why do they exist?

The more we study assumptions and filters, the more attuned we become to their prevalence. When we make a decision, we’ll remember to inquire abut ourselves before we inquire about the world around us. That will lead us to better decisions.

Naive Realism and Open Mindedness

It’s an apple!

We all think that what we see is real. If I see an apple in front of me, it’s because there really is an apple in front of me. Under different lighting conditions, however, the apple may change colors or even its shape. I may see part of it and assume that the rest of it is there.

Further, I may perceive it quite differently when I’m hungry than when I’m full. Other people may see the apple differently than I do. They may perceive different shapes or colors. They may recognize that it’s a rare heirloom apple and have a much different experience of it than I do.

Or, I may be distracted (inattentional blindness) and not see the apple at all. Does the apple disappear from reality or just my perception of reality?

In my critical thinking classes, I ask students to wander around our building and observe the architecture. When they return to class, I ask if they could confidently describe what they saw. The typical answer is “Sure, why not?” Then I ask each student to draw a map. As you can probably guess, the maps don’t even remotely resemble each other. So, which student saw reality?

In truth, we build little models of reality in our heads. Suellen’s model includes a lot of plants. Mine includes fewer plants and more cars. Our models are different. We literally see different things. But she’s very confident that what she’s seeing is reality. So am I.

The idea that I can perceive reality directly – as opposed to building a mental model of it – is usually known as naïve realism. Most of us are naïve realists for most of our lives.

Like my students, naïve realists are very confident in their perception. They don’t doubt what they see. Why would they? They see reality. It’s external and objective.

Naïve realists are also quite confident about any inferences they draw about reality. They base their inferences on concrete, verifiable reality. They start with an assured vision of the world and build outward from there. Conclusions based on concrete reality certainly seem to be realistic.

Naïve realists are often the opposite of what we would call open-minded. They know what they know with little or no doubt. (All of which may contribute to the Dunning-Kruger effect).

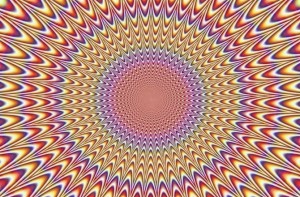

But what if you showed naïve realists optical illusions? What if you could show them that their perceptions differ from what other people perceive? What if you could show them illusions that demonstrate that they are creating reality as opposed to perceiving it? If you could, would they become more open minded?

It’s an interesting thought that William Hart and his colleagues recently pursued. The researchers randomly divided students into four different groups. One group completed an intelligence test, another read about chimpanzees, another read about naïve realism, and another read about naïve realism and then viewed a variety of optical illusions. (The original article is here; a less technical summary is here).

The researchers then asked all the students to read stories with ambiguous characters. Their personalities could be interpreted in multiple ways. Those who read about naïve realism and saw the illusions expressed more doubt about their interpretations and were more open to alternative explanations as compared to the other groups. They were more open-minded.

The study suggests that open mindedness may be fundamentally related to our perception of reality. Perhaps the more we learn about the ways we perceive reality, the more open-minded we’ll become. The Internet phenomenon, What color is this dress?, can only help.