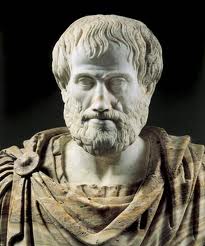

Aristotle, HBR, and Me

I love it when the Harvard Business Review agrees with me. A recent HBR blog post by Scott Edinger focuses on, “Three Elements of Great Communication, According to Aristotle“. The three are: ethos, logos, and pathos.

Ethos answers the questions: Are you credible? Why should I trust your recommendations? Logos is the logic of your argument. Is it factual? Do you have the evidence to back it up? (Interestingly, the more ethos you have,the less evidence you need to back up your logos. People will trust that you’re credible). Pathos is your ability to connect emotionally with your audience. If you have high credibility and impeccable logic, your audience might conclude that you could take advantage of them. Pathos reassures them that you won’t — your audience knows that you’re a good citizen.

When I teach people the arts of public speaking, I generally recommend that they start by establishing their credibility (ethos). The trick is to do this without overdoing it. If you come across as a braggart, you reduce your credibility rather than burnishing it. A good tip to remember is to use the word, “we” rather than “I”. “We” implies teamwork; “I” implies an egocentric psychopath.

After establishing your credibility, you proceed to the logic (logos) of your argument. What is it that you’re recommending and why do you think it’s a good solution for the audience’s needs? It’s often a good idea to start by defining the audience’s needs. Then you can fit the recommendation to the need. Keep it simple and use stories. Nobody remembers abstract logic and difficult technical concepts. They do remember stories.

Think about pathos both before the speech and in the conclusion. Ideally, you can meet the audience before your speech, ask insightful questions, and make personal connections. The more you can talk to members of the audience before the speech, the better off you’ll be. Look for anecdotes that you can use in your speech — that also builds your credibility. If nothing else, spend the last few minutes before your speech shaking hands with audience members and thanking them for coming to your speech. At the end of your speech, you can return to similar themes and express your appreciation. It’s also appropriate (usually) to point out how your recommendation will affect members of the audience personally. For instance, “We believe that our solution will help your company be more efficient. It will also help you build your career.”

Those of you who have followed my website for a while may remember my videos on ethos, logos, and pathos. I made them when I worked at Lawson Software and was teaching communication skills internally. Again, I’d like to thank Lawson for allowing me to use these videos on this website as I build my own practice.

By the way, all these suggestions apply to deliberative speeches. You present a logical argument and ask your audience to deliberate on it. On the other hand, you can also give a demonstrative speech where you throw the logic out altogether. They’re often called barn burners or stem winders. You can learn more here.

How To Be Unpersuasive

Not so fast!

Many of my articles focus on persuasion – how to persuade other people to do something because they want to do it. Today, let’s look at how not to be persuasive. I’ll again use Jay Conger’s article (click here), along with my own observations.

According to Conger, there are four common methods for being unpersuasive.

1) People attempt to make their case with the up-front hard sell. State your position and then sell it hard. When someone tries this on me, I just get stubborn. I’m not going to agree just because I don’t like their approach – even if I think there’s some merit to their argument. I push back simply because I don’t like to be pushed on.

2) They resist compromise. If you want me to agree with you, I first want to know that you take me seriously. I want to know that you’ll listen to me and accept my suggestions – at least some of them. If you blow off all my suggestions … well, no deal.

3) They think the secret of persuasion lies in presenting great arguments. I often run into this with technical people. They may think that the merits of their argument (or their product) are so clear and convincing, that they don’t need to “sell” the idea. It’s so obvious I’ll be compelled to agree. Again, I just don’t like to be compelled to do anything. Logic is necessary but not sufficient.

4) They assume persuasion is a one-shot effort. I’ve never been successful at selling much of anything with just one visit. The old wisdom still applies: listen first, establish your credibility, and then start to build your case … listening for concerns and suggestions as you do.

Bottom line: persuasion requires patience and persistence. Take your time.

Gross National Happiness

We’re happy in Denmark.

What’s with these Danes? On virtually every survey that purports to measure national happiness — or Gross National Happiness — Denmark scores number one. In fact, the Nordic countries — Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden — typically occupy half of the top ten “happy slots”. I’ve visited all the Nordic countries. They’re really nice but are they the happiest places in the world? Wasn’t Hamlet Danish? He didn’t seem so happy.

As you may have guessed, I’ve been reading the World Happiness Report published through The Earth Institute at Columbia University. (Click here). It’s about 170 pages long and makes for very interesting reading — enough so that I’m going to write about various facets of it from time to time. Here are some of the key questions:

- Is happiness a topic that we can take seriously? According to the study’s authors, there is enough empirical research coming from many different cultures that we can start to make useful comparisons and judgments. I’ll admit that I’m very curious about how to measure national happiness, so I’ll write about the method as well as the results.

- What makes people happy? Money helps but not as much as other factors like social cohesion, strong family ties, absence of corruption, and degree of personal freedom. Interestingly, giving money away seems to make people happier than receiving money.

- As countries get richer, do they get happier? Some do and some don’t. Apparently, the USA is one of those countries that hasn’t gotten happier as we’ve gotten richer. I’d like to dig into that.

- Is the world getting happier? Apparently we are, especially in areas where extreme poverty is being eliminated.

I’ll write occasionally on happiness studies and delve into what makes people happy and what doesn’t — and how all this affects the way we live. Feel free to send me any of your questions about happiness studies and I’ll try to get them answered.

In the meantime here are two questions for you:

- Taking all things together, how happy would you say you are? (0 = extremely unhappy; 10 = extremely happy)

- All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays? (0 = extremely dissatisfied; 10 = extremely satisfied).

In the Nordic countries, the average life satisfaction score is 7.6. If yours is lower than that, maybe it’s time to head to Denmark.

Persuasion and Self-Interest

Persuasive speakers often appeal to your self-interest. But which is more persuasive: appealing to your short-term or your long-term self-interest?

I’ve always guessed that the most persuasive arguments appeal to your short-term interests. I want results now … and I assume that most other people do, too. It just seems like common sense. But I haven’t had much empirical evidence to back up my position until I noticed an article on fitness and exercise by Jane Brody in today’s New York Times. (You can find it here).

I’ve always guessed that the most persuasive arguments appeal to your short-term interests. I want results now … and I assume that most other people do, too. It just seems like common sense. But I haven’t had much empirical evidence to back up my position until I noticed an article on fitness and exercise by Jane Brody in today’s New York Times. (You can find it here).

The article purports to be about exercise but it’s really about persuasion. How do you persuade people to take up exercise and stick with it? Traditionally we have “pitched” exercise either as a long-term benefit (“you’ll live longer”) or as a punishment (“you’re overweight; you have to work out”). As Brody points out, such messages are often sufficient to get people off the couch but rarely sufficient to keep them exercising long term.

Brody sums up the the need to focus on short-term benefits with a quote from Michelle Segar of the Univeristy of Michigan: “Immediate rewards are more motivating than distant ones. Feeling happy and less stressed is more motivating than not getting heart disease or cancer, maybe, some day in the future.”

So how does this affect your persuasive techniques? We’ve all experienced the difficulty of persuading people based on long-term interests. Perhaps you’ve tried to convince your children to study or save for the future. Or argued the politics of long-term environmental dangers. Or debated the future of programs like Social Security or Medicare. You’ll be more persuasive if you can focus your arguments on short-term benefits (and emotions) rather than long-term abstractions.

This may mean that you’ll leaven your argument with feelings and emotions more than facts and data. For instance, if you’re trying to persuade your children to save for the future, you might argue that, “If you save a little each day, your future will be secure.” That’s factual, future-oriented, and long-term. It’s also very abstract and fuzzy, especially to a young person. So you might try a different tack: “You’ll worry less and feel better if you know that your future is secure.” It’s more emotional and more immediate. It’s also more persuasive.

Activate Your Friends, Energize Your Enemies

In highly political situations, your ability to speak eloquently may actually work to your disadvantage. By speaking forcefully about a political objective, you may activate your friends but thoroughly energize your opponents. Your friends may support your objectives but without a great deal of energy. Your opponents, on the other hand, may be thoroughly alarmed by your presentations and highly  energized to oppose your initiative. You can provoke a strong immune response from your opponents that can swamp even the best laid plans.

energized to oppose your initiative. You can provoke a strong immune response from your opponents that can swamp even the best laid plans.

This happens regularly in political situations — especially during election campaigns. When one side speaks for something, the other side is motivated to increase the volume when speaking against it. Even if it’s a perfectly logical proposal, the mere fact that one side is pushing it hard may cause the other side to push back even harder.

Does this happen in business situations? All the time. But in business, the immune response is often cloaked. (In politics, the conflict is right out in the open — which may be healthier). If your business is highly political, you may find that speaking strongly for an initiative simply activates your opposition and weakens your position. If you think that’s happening to you, don’t stop speaking for your initiative but be sure to reach out to the opposition to look for common ground and areas of agreement. You need to make the first move — your opponents are not going to come to you. Look for private, face-to-face meetings with your opponents to clear the air and bridge the gap. You can learn more in the video.

By the way, the book I mention in the video is Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the U.S. Senate by France E. Lee. You can find it here on Amazon.