What We Don’t Know and Don’t See

It’s hard to think critically when you don’t know what you’re missing. As we think about improving our thinking, we need to account for two things that are so subtle that we don’t fully recognize them:

- Assumptions – we make so many assumptions about the world around us that we can’t possibly keep track of them all. We make assumptions about the way the world works, about who we are and how we fit, and about the right way to do things (the way we’ve always done them). A key tenet of critical thinking is that we should question our own thinking. But it’s hard to question our assumptions if we don’t even realize that we’re making assumptions.

- Sensory filters – our eye is bombarded with millions of images each second. But our brain can only process roughly a dozen images per second. We filter out everything else. We filter out enormous amounts of visual data, but we also filter information that comes through our other senses – sounds, smells, etc. In other words, we’re not getting a complete picture. How can we think critically when we don’t know what we’re not seeing? Additionally, my picture of reality differs from your picture of reality (or anyone else’s for that matter). How can we communicate effectively when we don’t have the same pictures in our heads?

Because of assumptions and filters, we often talk past each other. The world is a confusing place and becomes even more confusing when our perception of what’s “out there” is unique. How can we overcome these effects? We need to consider two sets of questions:

- How can we identify the assumptions were making? – I find that the best method is to compare notes with other people, especially people who differ from me in some way. Perhaps they work in a different industry or come from a different country or belong to a different political party. As we discuss what we perceive, we can start to see our own assumptions. Additionally we can think about our assumptions that have changed over time. Why did we used to assume X but now assume Y? How did we arrive at X in the first place? What’s changed to move us toward Y? Did external reality change or did we change?

- How can we identify what we’re not seeing (or hearing, etc.)? – This is a hard problem to solve. We’ve learned to filter information over our entire lifetimes. We don’t know what we don’t see. Here are two suggestions:

- Make the effort to see something new – let’s say that you drive the same route to work every day. Tomorrow, when you drive the route, make an effort to see something that you’ve never seen before. What is it? Why do you think you missed it before? Does the thing you missed belong to a category? Are you missing the entire category? Here’s an example: I tend not to see houseplants. My wife tends not to see classic cars. Go figure.

- View a scene with a friend or loved one. Write down what you see. Ask the other person to do the same. What are the differences? Why do they exist?

The more we study assumptions and filters, the more attuned we become to their prevalence. When we make a decision, we’ll remember to inquire abut ourselves before we inquire about the world around us. That will lead us to better decisions.

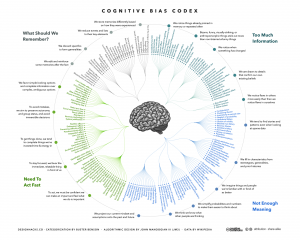

How Many Cognitive Biases Are There?

In my critical thinking class, we begin by studying 17 cognitive biases that are drawn from Peter Facione’s excellent textbook, Think Critically. (I’ve also summarized these here, here, here, and here). I like the way Facione organizes and describes the major biases. His work is very teachable. And 17 is a manageable number of biases to teach and discuss.

While the 17 biases provide a good introduction to the topic, there are more biases that we need to be aware of. For instance, there’s the survivorship bias. Then there’s swimmer’s body fallacy. And the Ikea effect. And the self-herding bias. And don’t forget the fallacy fallacy. How many biases are there in total? Well, it depends on who’s counting and how many hairs we’d like to split. One author says there are 25. Another suggests that there are 53. Whatever the precise number, there are enough cognitive biases that leading consulting firms like McKinsey now have “debiasing” practices to help their clients make better decisions.

The ultimate list of cognitive biases probably comes from Wikipedia, which identifies 104 biases. (Click here and here). Frankly, I think Wikipedia is splitting hairs. But I do like the way Wikipedia organizes the various biases into four major categories. The categorization helps us think about how biases arise and, therefore, how we might overcome them. The four categories are:

1) Biases that arise from too much information – examples include: We notice things already primed in memory. We notice (and remember) vivid or bizarre events. We notice (and attend to) details that confirm our beliefs.

2) Not enough meaning – examples include: We fill in blanks from stereotypes and prior experience. We conclude that things that we’re familiar with are better in some regard than things we’re not familiar with. We calculate risk based on what we remember (and we remember vivid or bizarre events).

3) How we remember – examples include: We reduce events (and memories of events) to the key elements. We edit memories after the fact. We conflate memories that happened at similar times even though in different places or that happened in the same place even though at different times, … or with the same people, etc.

4) The need to act fast – examples include: We favor simple options with more complete information over more complex options with less complete information. Inertia – if we’ve started something, we continue to pursue it rather than changing to a different option.

It’s hard to keep 17 things in mind, much less 104. But we can keep four things in mind. I find that these four categories are useful because, as I make decisions, I can ask myself simple questions, like: “Hmmm, am I suffering from too much information or not enough meaning?” I can remember these categories and carry them with me. The result is often a better decision.

Arguing Without Anger

Red people and blue people are at it again. Neither side seems to accept that the other side consists of real people with real ideas that are worth listening to. Debate is out. Contempt is in.

As a result, our nation is highly polarized. To work our way out of the current stalemate, we need to listen closely and speak wisely. We need to debate effectively rather than arguing angrily. Here are some tips:

It’s not about winning, it’s about winning over – too often we talk about winning an argument. But defeating an opponent is not the same as winning him over to your side. Aim for agreement, not a crushing blow.

It’s not about values – our values are deeply held. We don’t change them easily. You’re not going to convert a red person into a blue person or vice-versa. Aim to change their minds, not their values.

Stick to the future tense – the only reason to argue in the past tense is to assign blame. That’s useful in a court of law but not in the court of public opinion. Stick to the future tense, where you can present choices and options. That’s where you can change minds. (Tip: don’t ever argue with a loved one in the past tense. Even if you win, you lose.)

The best way to disagree is to begin by agreeing – the other side wants to know that you take them seriously. If you immediately dismiss everything they say, you’ll never persuade them. Start by finding points of agreement. Even if you’re at opposite ends of the spectrum, you can find something to agree to.

Don’t fall for the anger mongers – both red and blue commentators prey on our pride to sell anger. They say things like, “The other side hates you. They think you’re dumb. They think they’re superior to you.” The technique is known as attributed belittlement and it’s the oldest trick in the book. Don’t fall for it.

Don’t fall into the hypocrisy trap – both red and blue analysts are willing to spin for their own advantage. Don’t assume that one side is hypocritical while the other side is innocent.

Beware of demonizing words – it’s easy to use positive words for one side and demonizing words for the other side. For example: “We’re proud. They’re arrogant.” “We’re smart. They’re sneaky.” It’s another old trick. Don’t fall for it.

Show some respect – just because people disagree with you is no reason to treat them with contempt. They have their reasons. Show some respect even if you disagree.

Be skeptical – the problems we’re facing as a nation are exceptionally complex. Anyone who claims to have a simple solution is lying.

Burst your bubble – open yourself up to sources you disagree with. Talk with people on the other side. We all live in reality bubbles. Time to break out.

Give up TV — talking heads, both red and blue, want to tell you what to think. Reading your own sources can help you learn how to think.

Aim for the persuadable – you’ll never convince some people. Don’t waste your breath. Talk with open-minded people who describe themselves as moderates. How can you tell they’re open-minded? They show respect, don’t belittle, agree before disagreeing, and are skeptical of both sides.

Engage in arguments – find people who know how to argue without anger. Argue with them. If they’re red, take a blue position. If they’re blue, take a red position. Practice the art of arguing. You’re going to need it.

Remember that the only thing worse than arguing is not arguing – We know how to argue. Now we need to learn to argue without anger. Our future may depend on it.

Are Men Bigger Risk Takers Than Women?

Most people (in America at least) would probably agree with the following statement:

Men are bigger risk takers than women.

Several research studies seem to have documented this. Researchers have asked people what risky behaviors they engage in (or would like to engage in). For instance, they might ask a randomly selected group of men and women whether they would like to jump out of an airplane (with a parachute). Men – more often than women – say that this is an appealing idea. Ask about driving a motorcycle and the response is more or less the same. Men are interested, women not so much. QED: men are bigger risk takers than women.

But are we taking a conceptual leap here (without a parachute)? How do we know if something is true? What’s the operational definition of “risk”? Should we be engaging our baloney detectors right about now?

In her new book, Testosterone Rex, Cordelia Fine suggests that we’ve pretty much got it all backwards. The problem with using skydiving and motorcycle driving as proxies for risk is that they are far too narrow. Indeed, they are narrowly masculine definitions of risk. So, in effect, we’re asking a different question:

Would you like to engage in activities that most men define as risky?

It’s a circular argument. We give a masculine definition of risk and then conclude that men are more likely to engage in that activity than women. No duh.

Fine points out that, “In the United States, being pregnant is about 20 times more likely to result in death than is a sky dive.” So which gender is really taking the big risks?

As with so many issues in logic and critical thinking, we need to examine our definitions. If we define our variables in narrow ways, we’ll get narrow and – most likely – biased results.

Fine writes that many people believe in Testosterone Rex – that differences between man and women are biological and driven largely by hormonal effects. But when she examines the evidence, she finds one logical flaw after another. Researchers skew definitions, reverse cause-and-effect, and use small samples to produce large (and unsupported) conclusions.

Ultimately, Fine concludes that we aren’t born as males and females in the traditional way that we think about gender. Rather, when we’re born, society starts to shape us into society’s conception of what the gender ought to be. It’s a bracing and clearly argued point that seems to be backed up by substantial evidence.

It’s also a great example of baloney detection and a good case study for any class in critical thinking.

(I’m taking a risk here. I haven’t yet read Testosterone Rex. I based this commentary on four book reviews. You can find them here: Guardian, Financial Times, NPR, and New York Times).

Factory-Installed Biases

In my critical thinking class, we investigate a couple of dozen cognitive biases — fallacies in the way our brains process information and reach decisions. These include the confirmation bias, the availability bias, the survivorship bias, and many more. I call these factory-installed biases – we’re born this way.

But we haven’t asked the question behind the biases: why are we born that way? What’s the point of thinking fallaciously? From an evolutionary perspective, why haven’t these biases been bred out of us? After all, what’s the benefit of being born with, say, the confirmation bias?

Elizabeth Kolbert has just published an interesting article in The New Yorker that helps answer some of these questions. (Click here). The article reviews three new books about how we think:

- The Enigma of Reason by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber

- The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone by Steve Sloman and Philip Fernbach

- Denying To The Grave: Why We Ignore The Facts That Will Save Us by Jack Gorman and Sara Gorman

Kolbert writes that the basic idea that ties these books together is sociability as opposed to logic. Our brains didn’t evolve to be logical. They evolved to help us be more sociable. Here’s how Kolbert explains it:

“Humans’ biggest advantage over other species is our ability to coöperate. Coöperation is difficult to establish and almost as difficult to sustain. For any individual, freeloading is always the best course of action. Reason developed not to enable us to solve abstract, logical problems or even to help us draw conclusions from unfamiliar data; rather, it developed to resolve the problems posed by living in collaborative groups.”

So, the confirmation bias, for instance, doesn’t help us make good, logical decisions but it does help us cooperate with others. If you say something that confirms what I already believe, I’ll accept your wisdom and think more highly of you. This helps us confirm our alliance to each other and unifies our group. I know I can trust you because you see the world the same way I do.

If, on the other hand, someone in another group says something that disconfirms my belief, I know the she doesn’t agree with me. She doesn’t see the world the same way I do. I don’t see this as a logical challenge but as a social challenge. I doubt that I can work effectively with her. Rather than checking my facts, I check her off my list of trusted cooperators. An us-versus-them dynamic develops, which solidifies cooperation in my group.

Mercier and Sperber, in fact, change the name of the confirmation bias to the “myside bias”. I cooperate with my side. I don’t cooperate with people who don’t confirm my side.

Why wouldn’t the confirmation/myside bias have gone away? Kolbert quotes Mercier and Sperber: ““This is one of many cases in which the environment changed too quickly for natural selection to catch up.” All we have to do is wait 1,000 generations or so. Or maybe we can program artificial intelligence to solve the problem.