Strategy: Who’s Number 2?

The CEO is clearly the most important executive when it comes to creating and implementing organizational strategy. Who’s the second most important executive for strategy?

The standard answer is probably the Chief Operation Officer — especially in terms of carrying out the strategy. But I’m starting to think that the COO is only the third or fourth most important strategic officer. So, who’s number 2? I’m leaning towards the head of Human Resources. Let’s call him or her the Chief Human Resources Officer or CHRO.

I’m leaning toward the CHRO because I’ve always believed that the soft stuff is hard. It’s not easy to get your culture right or to motivate employees for the long haul. It is all too easy to get your strategy crosswise with your culture. As I’ve noted before , when it’s culture versus strategy, culture always wins.

Similarly, I’ve never seen a company falter because they couldn’t find enough “numbers guys”. Our B-schools just keep churning them out. On the other hand, I have seen companies falter because they couldn’t find good communicators and motivators. Understanding human behavior is much more difficult than understanding the numbers. While we can teach people the “soft arts,” it doesn’t seem to be a popular specialty at university.

What’s really pushing me toward the CHRO as strategy leader is Scott Keller and Colin Price’s book, Beyond Performance: How Great Organizations Build Ultimate Competitive Advantage. (Click here for the book or here for a white paper). Keller and Price argue that too many companies pay close attention to performance (“the numbers”) but not nearly enough attention to organizational health. Their “…central message is that focusing on organizational health — the ability of your organization to align, execute, and renew itself faster than the competition — is just as important as focusing on the traditional drivers of business performance.” This has everything to do with the “people-oriented aspects of leading an organization.” In my mind, that means the CHRO better be intimately involved.

Keller and Price present a lot of statistical evidence to buttress their case. (They are McKinsey guys, after all). There is a distinct correlation between organizational health and organizational performance. They also present five “frames” for viewing both health and performance during transformation change: 1) Aspire; 2) Assess; 3) Architect; 4) Act; 5) Advance. I’ll write more about these in the future but the bottom line is that you need to use these frames to view both performance and health to develop a sustainable, high performance organization.

While I think the CRHO could and should be a strategy leader, in my experience, it doesn’t happen very often. I’ve seen HR organizations launch very interesting programs but, too often, the programs exist in their own right rather than as strategic enablers. They don’t impede the strategy but they don’t help it either. I also see the numbers guys set the strategy and then turn to the CHRO and say, in effect, “OK, here’s the strategy, now get us the people we need.” (In technology, this happens to CIOs all the time). To be effective, the CHRO really needs to be at the strategy table.

Why wouldn’t the CHRO be invited to the strategy table? Perhaps because they understand the soft stuff but not the business. I’ve seen CHROs (and CIOs) make naive comments in strategy meetings, showing that they clearly don’t understand the business. The result is a bunch of numbers guys rolling their eyeballs and looking vaguely embarrassed. Numbers guys need to learn more about the soft stuff. By the same token, CHROs (and their staffs) need to learn more about the performance side of the business. Perhaps then, they can truly become strategy leaders.

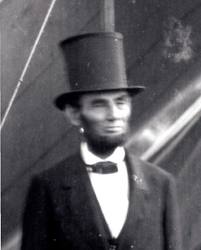

Little Life Lessons from Lincoln

On July 4, 1863, Robert E. Lee was leading a Confederate army in retreat from Gettysburg when they were trapped against the rain-swollen Potomac River. The Union army, commanded by General George Meade, pursued the rebels. Abraham Lincoln ordered Meade to attack immediately. Instead, Meade dithered, the weather cleared, the river shrank, and Lee and his army escaped. Lincoln was furious and penned this letter to Meade:

I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within our easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely. If you could not safely attack Lee last Monday, how can you possibly do so south of the river, when you can take with you very few— no more than two-thirds of the force you then had in hand? It would be unreasonable to expect and I do not expect that you can now effect much. Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.

Interestingly, Lincoln never sent the letter — it was found among his papers after his death. Lincoln generally praised his colleagues for their positive accomplishments and said little or nothing about their failures. Apparently, he wrote letters like the one to Meade to relieve his own frustrations — and perhaps to leave a record for history — rather than to humiliate his colleagues and create public acrimony.

As Douglas Wilson, a Lincoln scholar, pointed out in a recent article (click here), Lincoln was great communicator but not necessarily in the way we think. Some tidbits on how he worked:

- He rarely spoke in public and when he did he was very well prepared. We think of the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural speech as great feats of oratory — and they were. But there weren’t many such feats; he gave relatively few speeches. And he almost never spoke off the cuff. He knew that people followed his words closely and he prepared meticulously. His speeches were extraordinary. Equally extraordinary is the fact that he almost never said anything stupid that he had to retract. Our politicians and executives today could learn a lot from him.

- He pre-wrote his speeches. Lincoln always had scraps of paper with him — which he often stored in his hat. When an idea — or an elegant way to phrase an idea — came to him, he jotted it down. He didn’t start thinking about his speeches when a deadline drew near. He was thinking about them virtually all the time.

- He was mercifully brief. The Gettysburg Address consisted of 267 words. By contrast, this post has about 600. Which one do you think will live longer?

- He cultivated the press before he needed them. In general, Lincoln got to know his audience before he spoke to them. He gave favors to journalists before he asked for favors in return. Getting to know your audience and letting them know that you genuinely care about them are always good strategies.

- He understood event jujitsu. The Civil War began with the crisis at Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. Lincoln could have sent in a fleet to shoot up the Confederate fortifications. Instead, he sent in a small re-supply mission. When the Confederates sought to block the mission, they fired the first shots of the war. It’s a small leap to conclude that the Confederates “started” the war. Thus, a small incident became a major victory in the battle to shape perceptions.

Lincoln has always been one of my favorite presidents and I certainly enjoyed the recent movie from Steven Spielberg. Lincoln communicated effectively and was an expert at shaping public opinion. As the movie showed, he was also adept at cutting deals and rolling logs to achieve his greater goals. Not bad for a kid from the prairies.

Bring Your Husband To Heel

It’s not so difficult.

Some years ago, Suellen and I were vacationing in England when we came across a tempest in a teapot in the local newspapers. It seems that a woman who was widely regarded as the best dog trainer in the country had written a book about husband training. Titled Bring Your Husband to Heel, the book suggested that training a husband was really not that different from training a dog. (Disclosure: I may have misremembered the book’s title. I can’t find it on the web.)

Letters to the editor in the local papers fell into three categories. The first group lamented, “This is terrible. It’s an insult to husbands.” The second group wrote, “This is terrible. It’s an insult to dogs.” The third group, which was composed only of women, wrote, “This is terrible. How dare she divulge our secrets?”

So what were the secrets? The essential advice was: Ignore bad behavior. Reward good behavior. As the author pointed out, dogs don’t really understand what they’ve done wrong, even if you tell them in a very loud voice. On the other hand, they do understand what it means to get a treat. If they need to behave a certain way to get a treat, then they’ll do it.

The secret to ignoring bad behavior is to not take it personally. With a dog, that’s easy. We usually don’t conclude that Fido is angry and vengeful just because he knocked over a lamp with a wagging tail. With a spouse, however, it’s harder. We may conclude that he or she is taking it out on us.

The author’s advice: get over it. Criticizing gets you nowhere. Telling a husband he’s messy doesn’t change the behavior. Besides, he probably already knew that. Telling him repeatedly doesn’t change the equation. So, ignore it and focus on rewarding the behaviors that you like. As “good” behaviors accumulate, they start to crowd out “bad” behaviors.

I was reminded of the book by one of David Brooks’ recent columns in the New York Times. Brooks tells the story of another Briton, Nick Crews, who wrote a letter telling his three grown children that they were “bitter disappointments” and he was sick and tired of them. The letter went viral (it’s known as the Crews Missile) and many parents, apparently, wished they had written it. As Brooks’ points out, however, “…no matter how emotionally satisfying these tirades may be, they don’t really work…. There’s a trove of research suggesting that it’s best to tackle negative behaviors obliquely, by redirecting attention toward different, positive ones.”

So the dog trainer apparently had it right. Want a better-behaved husband? Easy. Just give him treats.

Three Things Not To Do

Yesterday, I wrote about four ways to be unpersuasive — in the broadest sense. Today, let’s narrow the focus and talk about three things not to do in public speaking. These are behaviors that I see all too frequently and they detract from your effectiveness and your persuasiveness. (For my tips on three things you should do, click here).

-

No ned to apologize.

Don’t fumble around — I see far too many presenters using the first five to ten minutes of their time fumbling around with their technology. As you’re trying to find your PowerPoint file, I’m reading your desktop — and I often find some very interesting tidbits. Show up early, make sure everything works, and be ready when the audience shows up. Even more radical — give a presentation without using PowerPoint. That simplifies everything.

- Don’t apologize — if you apologize for yourself, you undercut your own position. If you don’t take yourself seriously, why would anyone else? You have a right to be there. Step forward and seize the moment.

- Dont forget the housekeeping — the most important housekeeping items are to agree on the time and on how you’ll handle questions. If you’ve misunderstood how much time you have (or if your audience’s schedule has changed), you may have to adjust your presentation on the fly. Always double check what the audience expects of you in terms of time and feedback.

You can learn more in the video. Speaking of which, this is a good opportunity to acknowledge again that I started this video series when I was still an executive at Lawson. When I retired, Lawson very graciously permitted me to use the videos to build my own practice. I certainly appreciate it.

Where Does Credibility Come From?

According to the Greeks, a persuasive presentation consists of three major elements:

- Ethos (trust) — first you need to establish that you are a trustworthy person. (Click here for more).

- Logos (logic) — once you’re perceived as trustworthy (and only then), you can deliver the logic of your argument. (Click here).

- Pathos (emotion) — to sum up, you need to touch on the audience’s emotions. Why is your recommendation good for them? (Click here).

I’ve always wondered, how do you quickly establish that you’re a trustworthy person? It’s not easy to project trustworthiness to an audience. Credibility is certainly a key ingredient — but that just begs the question, how do you project credibility?

Then I re-read Jay Conger’s article (click here) and discovered that credibility comes from two sources: experience and relationships.

I intuitively understood the experience part. Whenever I speak to an audience, I briefly introduce the relevant details of my experience. I try not to overdo it as I don’t want to come across as arrogant or academic. I find that a little self-deprecation can help. This is typically a variant on, “I know a lot about the topic because I’ve made a lot of mistakes….” Ultimately, however, I want the audience to know that I have been successful. To do this, I often find it helpful to have someone else introduce me. They can brag about me in ways that I can’t.

Conger points out that credibility also includes open-mindedness. Persuasive people are often perceived as good listeners as well as good speakers. They can incorporate what their audience has to say and adjust their positions. This is the relationship aspect of credibility. People who are honest, even-keeled, and who “generously share credit” are perceived as more credible and trustworthy.

But what if your audience doesn’t know that you are honest, even-keeled, and appreciative? What if you’re speaking to the audience for the first time? I find it’s very useful to interview members of the audience before I give a presentation. Then I can discuss my experiences and what I’ve learned. I’m more credible simply because I listened before speaking.

I also like to speak to the audience’s customers before a presentation. Because I’m an outsider, I can ask “dumb” questions of customers. This often produces interesting, even unique, insights that I can pass on to the audience. That demonstrates that I’m open to interesting sources of information and that I have some interesting perspectives to share. That makes me more credible and more persuasive.

Before you approach an audience, think about how you’ll build your credibility and trustworthiness. If you establish that you’re trustworthy early in the presentation, you may well succeed. If you can’t establish your credibility, the rest of your presentation is just wasted time.