Premature Commitment. It’s a Guy Thing.

There’s a widespread meme in American culture that guys are not good at making commitments. While that may be true in romance, it seems that the opposite — premature commitment — is a much bigger problem in business.

That’s the opinion I’ve formed from reading Paul Nutt’s book, Why Decisions Fail. Nutt analyzes 15 debacles which he defines as “… costly decisions that went very wrong and became public…” Indeed, some of the debacles — the Ford Pinto, Nestlé infant formula, Shell Oil’s Brent Spar disposal — not only went public but created firestorms of indignation.

While each debacle had its own special set of circumstances, each also had one common feature: premature commitment. Decision makers were looking for ideas, found one that seemed to work, latched on to it, pursued it, and ignored other equally valid alternatives. Nutt doesn’t use the terminology, but in critical thinking circles this is known as satisficing or temporizing.

Here are two examples from Nutt’s book:

Ohio State University and Big Science — OSU wanted to improve its offerings (and its reputation) in Big Science. At the same time, professors in the university’s astronomy department were campaigning for a new observatory. The university’s administrators latched on to the observatory idea and pursued it, to the exclusion of other ideas. It turns out that Ohio is not a great place to build an observatory. On the other hand, Arizona is. As the idea developed, it became an OSU project to build an observatory in Arizona. Not surprisingly, the Ohio legislature asked why Ohio taxes were being spent in Arizona. It went downhill from there.

EuroDisney — Disney had opened very successful theme parks in Anaheim, Orlando, and Tokyo and sought to replicate their success in Europe. Though they considered some 200 sites, they quickly narrowed the list to the Paris area. Disney executives let it be known that it had always been “Walt’s dream” to build near Paris. Disney pursued the dream rather than closely studying the local situation. For instance, they had generated hotel revenues in their other parks. Why wouldn’t they do the same in Paris? Well… because Paris already had lots of hotel rooms and an excellent public transportation system. So, visitors saw EuroDisney as a day trip, not an overnight destination. Disney officials might have taken fair warning from an early press conference in Paris featuring their CEO, Michael Eisner. He was pelted with French cheese.

In both these cases — and all the other cases cited by Nutt — executives rushed to judgment. As Nutt points out, they then compounded their error by misusing their resources. Instead of using resources to identify and evaluate alternatives, they invested their money and energy in studies designed to justify the alternative they had already selected.

So, what to do? When approaching a major decision, don’t satsifice. Don’t take the first idea that comes along, no matter how attractive it is. Rather, take a step back. (I often do this literally — it does affect your thinking). Ask the bigger question — What’s the best way to improve Big Science at OSU? — rather than the narrower question — What’s the best way to build a telescope?

Social Media for Business Leaders

As a marketing guy, I understand (sort of) the marketing aspects of social media. If you can start a conversation — and keep it interesting — you can engage your market in ways that are impossible with “interruption marketing”. You can exchange ideas, gather suggestions, support charities, and engage in positive social activities. Along the way, you can mention your products. You offer something of interest (or utility) and the products tag along for the ride.

As a marketing guy, I understand (sort of) the marketing aspects of social media. If you can start a conversation — and keep it interesting — you can engage your market in ways that are impossible with “interruption marketing”. You can exchange ideas, gather suggestions, support charities, and engage in positive social activities. Along the way, you can mention your products. You offer something of interest (or utility) and the products tag along for the ride.

But social media is not just about marketing. Executives should be able to use social media to enhance both internal and external communication. Yet, I haven’t found many examples in the literature. Fortunately, McKinsey just published an interesting case study based on GE’s experience. The authors, who are GE leaders themselves, point out that GE is not a “digital native” and its experiences may, therefore, be relevant to a wide range of organizations. They then outline six social media skills that all leaders need to learn. The first three are personal; the last three are strategic or organizational.

Producer — creating compelling content. Digital video tools are now widely available and easy to use. Even busy senior executives can weave them into their communications. As compared to traditional top-down communications, the emphasis shifts from high production quality to authenticity. The goal is to invite participation and collaboration. Speaking plainly and telling stories in an authentic voice invites participation much better than a highly produced video.

Distributor — leveraging dissemination dynamics. Instead of sending a message and expecting it be consumed, you now send a message and expect it to be mashed up. A successful social message will be picked up by people at all levels of the organization, commented on, “recontextualized”, and forwarded along. You want this to happen which means giving up a significant amount of control — not always an easy concept for executives. You also want to build up a followership within the organization long before you need it.

Recipient — managing communication overflow. We’re already drowning in information. Why take on social media? Because it’s more credible than top-down media. By learning to use filters effectively, you can also use social media to manage the flow of information to and from your desk. You should practice when and how to respond to postings and tweets. You don’t need to respond frequently but you do need to respond thoughtfully.

Advisor and orchestrator — driving strategic social media utilization. Fundamentally, executives need to promote the use of social media and guide it to maturity. Your company may be enthusiastic but inexperienced. Or you may have leaders who wish to avoid it altogether. A good leader can harness the enthusiasm of “digital natives” and even use them as “reverse mentors” to build capabilities within the organization.

Architect — creating an enabling organizational infrastructure. On the one hand, you want to encourage collaboration and free exchange. On the other hand, you need some rules. It helps if you have well-established values of integrity, collaboration, and transparency. If your company hasn’t established these values, it’s time to get started. Social media will arise in your organization whether you’re ready or not.

Analyst — staying ahead of the curve. As your organization masters social media, something new will emerge. Perhaps, it’s the Internet of Things. As I’ve noted before, this could help us reduce health care costs. It could also have huge implications for your organization — both good and bad. Better stay awake.

And what do you get if your company’s leaders master these skills? The authors say it best: “We are convinced that organizations that … master … organizational media literacy will have a brighter future. They will be more creative, innovative, and agile. They will attract and retain better talent, as well as tap deeper into the capabilities and ideas of their employees and stakeholders.”

Want to Be More Innovative? Move to Boulder. Or Sweden.

In an earlier post, I pointed out that cities generate much more than their “fair” share of innovations. The reason is simple: there’s more opportunity to run into new ideas, concepts, and people. It turns out that innovation is even more concentrated than I thought. Just 20 of the America’s 370 metropolitan statistical areas — accounting for 34% of the population — produce 63% of the nation’s patents. The top five patent-producing metropolises in the U.S. (in order) are: San Jose, CA, Burlington, VT, Rochester, MN, Corvallis, OR, and Boulder, CO. These areas account for 12% of the U.S. population but 30% of American patents.

In an earlier post, I pointed out that cities generate much more than their “fair” share of innovations. The reason is simple: there’s more opportunity to run into new ideas, concepts, and people. It turns out that innovation is even more concentrated than I thought. Just 20 of the America’s 370 metropolitan statistical areas — accounting for 34% of the population — produce 63% of the nation’s patents. The top five patent-producing metropolises in the U.S. (in order) are: San Jose, CA, Burlington, VT, Rochester, MN, Corvallis, OR, and Boulder, CO. These areas account for 12% of the U.S. population but 30% of American patents.

The finding comes from a new Brooking’s Institute report on patents. Some other highlights:

- The pace of patenting in the U.S. continues to climb. The growth of patent applications slowed after the IT bubble burst but is now at an all time high.

- Though the pace has increased, the U.S. ranks ninth in the world in terms of patents per capita. The countries ahead of the U.S are (in order): Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, Israel, the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, and Japan. (Those pesky Scandinavians are at the top again).

- The average patent is worth about $500,000 in direct market value — and much more as it diffuses through the economy.

- The last period of great patent growth in the United States fell between the Civil War and the early 20th century. We “democratized” invention during that period — with many patents coming from blue-collar workers who were not professional researchers. Today, patents are more complicated, more difficult and expensive to obtain, and require more education. The ability to create patents is concentrated in fewer organizations in fewer places.

- The price per patent is rising in the U.S.. From 1953 to 1974, $1.8 million in R&D spending generated one patent. Since 1975, the cost has been $3.5 million (in inflation adjusted dollars).

- Almost half (48%) of the patents granted in the U.S. from 2006 through 2010 could be grouped into the Big Ten categories: Communications, Computer Software, Semiconductors, Computer Hardware, Power Systems, Electrical Systems, Biotech, Measuring & Testing, Information Storage, Transportation. The top five categories account for slightly more than 30% of all patents.

- Patent ownership has become broader and more competitive. Of the top ten patent producing companies from 1976 to 1980, only four were in the top 10 in 2011-2012: IBM, GE, GM, and AT&T.

- The federal government dominated R&D spending up to approximately 1970. By the late 1970s, the federal government share fell below half. In 2009, the government share of R&D spending was about one-third. Roughly 60% of federal R&D spending goes to private companies, 30% goes to universities (including university-administered national labs).

- Metropolitan areas that lead in patent production also lead the nation in terms of of productivity growth. They also enhance local employment opportunities and generate a disproportionate number of initial public offerings (IPOs).

The Brooking Report provides ample evidence that the research and innovation that lead to patents has a dramatic impact on local economies, employment, and growth. Bottom line: if you want your city to grow, don’t build a football stadium. Build a research university. Or move to Boulder.

Seven Strategies (But Not For Success)

What strategies don’t work? I had been trying to organize bad strategies into a mental map when I came across an article in The Economist that did the heavy lifting for me. In its own pithy way, The Economist names and shames six strategies that just don’t work. To that, I’ll add a seventh.

What strategies don’t work? I had been trying to organize bad strategies into a mental map when I came across an article in The Economist that did the heavy lifting for me. In its own pithy way, The Economist names and shames six strategies that just don’t work. To that, I’ll add a seventh.

Here are The Economist’s six along with my own pithy observations.

The Do-It-All strategy — don’t make the hard product choices. When you find market opportunities, pursue all of them. If you build enough products, something is bound to sell. This is sometimes known as the Food-Fight strategy — throw a bunch of food at the wall and see what sticks.

The Don Quixote strategy — launch a frontal attack on your strongest competitor. Take the fight right to them. It sounds bold — and everybody wants to be bold these days — but it’s well nigh suicidal. Its main advantage compared with the Do-It-All strategy: it’s over quickly. As Sergeant York taught us, don’t fire at the lead goose in the flying wedge. Fire at the last one and work your way forward.

The Waterloo strategy — fight on too many fronts at once. Rather than carving up the battlefield to your advantage, attack multiple enemies at once. That’ll teach ’em. Just like at Waterloo.

The Something-for-Everyone strategy — what’s our target market? Anyone who has money. This is often found in combination with the Do-It-All strategy. We’ve got lots of products, so let’s find lots of customers. One of the strengths of Lawson Software’s strategy is that we were very clear about who we served and who we didn’t. We turned down prospective customers who didn’t fit our profile. We couldn’t serve them successfully without distracting attention from our priority customers.

The Programme-of-the-Month strategy — first it was Pursuit of Excellence, then it was Built to Last, then it was … well, whatever the latest hot business book is. We’re dedicated to pursuing the fashionable strategy of the moment. Better to pick a simple strategy and stick with it.

The Dreams-That-Never-Come-True strategy — ambitious mission statements are never translated into clear choices. At some point, you have to come down out of the clouds and pursue this market (as opposed to that one) with this plan (as opposed to that one). It’s about making choices.

To The Economist Six, I’ll add a seventh:

The Military/Territorial strategy — the market is like a piece of territory that multiple armies are fighting over. There’s only so much territory; it can’t be expanded. If a competing army wins more of it, we will win less of it. It’s a zero sum. We have to stay focused on the competition and counter every maneuver. It’s a popular analogy but a bad one. War is about defeating the enemy. Business is about winning the customer. Focusing on the competition won’t get you there.

As I’ve written before, strategy is about what you don’t do. It’s about making hard choices that allow you to focus on markets or products or customers where you have the greatest chance of success. Forget everything else.

Strategy: Five Components

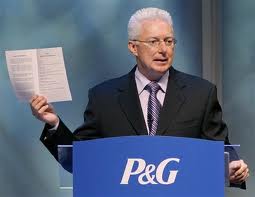

A.G Lafley is justifiably famous for taking over Procter & Gamble (P&G) and converting an insular company into a customer-centric, outward-looking culture known for a string of successful innovations. When Lafley became CEO in 2000, innovation was driven by thousands of in-house R&D designers, researchers, and engineers. They created neat stuff and “pushed” it to customers. Partially as a result, P&G’s success rate with new products and brands hovered around 15%. The R&D teams focused internally; only about 10% of new products came from outside the company.

Lafley essentially turned the company inside-out by putting the customer at the head of the innovation process. P&G called it Connect + Develop and emphasized collaboration with other departments, customers, and even outside research organizations. Lafley changed the culture from “not invented here” to “proudly found elsewhere”. P&G signed more than 1,000 collaborative agreements with outside organizations. It was a fundamental cultural change and the results were spectacular. According to a report from A.T. Kearney, “During Lafley’s tenure, sales doubled, profits quadrupled, and the company’s market value increased by more than $100 billion”.

Now Lafley has written a book, Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works, with Roger Martin, the Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the Univeristy of Toronto. Martin was Lafley’s “principal external strategy advisor”. In addition to Martin, Lafley built a brain trust of outside thinkers including designers and business professors. The eclectic nature of the group created many different “idea collisions” that generated process innovations as well as product innovations.

I’m sure that I’ll write a lot about the book in the future but it’s not quite out yet. It debuts in February. Today, I’m depending on the report from A.T. Kearney and a lengthy review from The Economist. One of the key insights is that P&G followed a strategy composed of five elements, each designed to help managers make the right decisions. These are:

- What does winning look like? What are we aiming for and what information do we look for along the way to help us understand if we’re making progress? Do we seek global domination, regional, or local?

- Which markets should we play in? Of course, this also implies another question: which markets should we ignore (or exit)? How do we determine which is which?

- How do we win? What’s our distinctive strategy in each market and category?

- What are our strengths and weaknesses and how do we deploy them in each market, against each competitor?

- What needs to be managed for the strategy to succeed? Of course, the inverse of this question is what doesn’t need to be managed? The Economist reports that one of Lafley’s “most important innovations was a slimmed-down strategy-review process … [that] replaced needlessly sprawling bureaucratic meetings….”

It’s a good story and an intriguing look at strategy. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have an entirely happy ending. The Economist reports that P&G has “stumbled badly” since Lafley left in 2009. Similarly, Martin’s consulting firm “got into financial difficulty and has been sold at a discount.” Still, the questions are relevant to any company’s strategy and the story is intriguing. I’ll report more soon.