Critical Thinking, Framing, and Red Wine

What else should I have?

I like wine, especially red wine. My tastes range from elegant to earthy. In fact, I’m not terribly discriminating – I like to sample them all.

I also feel the need to justify my red wine indulgences. So I’m always looking for news about the positive health effects of drinking red wine. (This is a classic case of System 2 rationalizing a decision that was initially made – for entirely different reasons — in System 1. My System 1 made the decision; my System 2 justifies it.)

As you may know, there’s plenty of good news about red wine and good health. Generally, drinking red wine is associated with better health and longer life. It’s a J-shaped curve, “…light to moderate drinkers have less risk than abstainers, and heavy drinkers are at the highest risk.” Drink a little bit and you get healthier; drink too much and you get unhealthier.

Is there a cause-and-effect relationship here? It certainly hasn’t been proven. All we’ve been able to show so far is that there is a correlation. A change in one variable is correlated to a change in another variable. Just because variable A happens before variable B, doesn’t mean that A causes B. (That would be the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy as the President points out in West Wing).

Yet many scientists have assumed that there is a cause-and-effect relationship and framed their studies accordingly. The typical approach is to break down the various elements of red wine to isolate the ingredient(s) that cause the beneficial health results. Is it ethanol? Is it resveratrol? Notice the assumption: there is something in the wine that causes the beneficial health result. The studies are narrowly framed.

Is this good critical thinking? Maybe not. Maybe we’re framing too tightly and assuming too much. Maybe there’s a third variable that causes us to drink red wine and be healthier.

I started thinking about this when I stumbled across a study conducted in Denmark more than a decade ago. The Danish researchers didn’t study wine. Rather, they looked at human behavior. More specifically, they looked at 3.5 million grocery store receipts.

The Danish researchers asked three interrelated questions: 1) What do wine drinkers eat? 2) Is this different from what non-wine-drinkers eat? 3) If so, could the differences in overall diet be the cause of the health effect?

The researchers looked at several specific combinations:

- What else did people who bought wine – but not beer – buy at the grocery store? (This group comprised 5.8% of the 3.5 million receipts)

- What else did people who bought beer – but not wine – buy at the grocery store? (6.6% of the total receipts).

- What else did people who bought both beer and wine buy at the grocery store? (1.2% of the total receipts).

I won’t try to summarize everything but here’s the key finding:

“This study indicates that people who buy (and presumably drink) wine purchase a greater number of healthy food items than those who buy beer. Wine buyers bought more olives, fruit or vegetables, poultry, cooking oil, and low fat products than people who bought beer. Beer buyers bought more ready cooked dishes, sugar, cold cuts, chips, pork, butter, sausages, lamb, and soft drinks than people who bought wine. Wine buyers were more likely to buy Mediterranean food items, whereas beer buyers tended to buy traditional food items.”

So, does wine cause good health? Maybe not. Maybe we framed the question improperly. Maybe we’ve been studying the wrong thing. Maybe it’s the other things that wine drinkers do that improve our health. As usual, more studies are needed. While I wait for the results, I think I’ll have a nice glass of Priorat.

Maps, Isms, and Assumptions

Looks good to me.

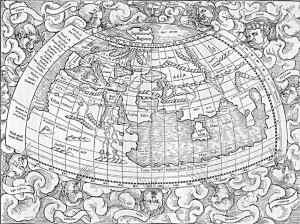

I have a map printed in Germany around 1530 that shows the world as it was seen by second century Greeks. Why would Europeans print a map that was based on sources roughly 15 centuries old? Because Europeans assumed the Greeks knew what they were doing.

Claudius Ptolemy, a Greek mathematician living in Alexandria, wrote a textbook called Geography in 150 AD. The book was so popular and reprinted so frequently – often in Arabic – that Ptolemy became known as the Father of Geography.

My map bears the heading, Le Monde Selons Ptol. or The World According to Ptolemy. It doesn’t include America even though it was printed roughly 40 years after Columbus sailed and roughly 25 years after the Waldeseemüller map became the first map ever to use the word “America”.

When my map was printed, Europe was going through an intellectual revolution. The basic question was: should we believe our traditional sources or should we believe our eyes? Should we copy Greek and Arabic sources or should we observe the world around us? Should we simply accept the Greek version of the world (as we have for so many centuries) or is “progress” something we can realistically aim for?

For centuries, Europeans assumed that the Greeks knew it all. There was no point observing the world and learning new tricks. One could live the best life by bowing to tradition, authority, and faith. This assumption held, in many quarters, until the early 16th century. Then it rapidly changed. You can see it in the maps. By 1570, most maps were in the style of tavola nuova — new maps — based on actual observations. The world had changed and, indeed, the tavolas nuovas look quite a bit like the maps we’re familiar with.

Let’s fast forward to 1900. What did we assume then? Three isms dominated our thinking: Darwinism, Marxism, and Freudianism. Further, we assumed that physics was almost finished – we had only a few final problems to work out and then physics would be complete. We assumed that we were putting the finishing touches on our knowledge of ourselves and the world around us.

But, of course, we weren’t. Today, Darwinism survives (with some enhancements) but Marxism and Freudianism have been largely cast aside. And physics is nowhere near complete. In fact, it seems that the more we learn, the more confused we become.

Even in my lifetime, our assumptions have changed dramatically. We used to believe that economics was rational. Now we understand how irrational our economic decisions are. We once assumed that the bacteria in our guts were just along for the ride. Now we believe they may fundamentally affect our behavior. We used to believe that stress caused ulcers. Now we know it’s a bacteria. Indeed, we seem to have gotten many things backwards.

And what are we assuming to be true today that will be proved wrong tomorrow? In the 16th century, we believed in eternal truths handed down for centuries. I suspect the 21st century won’t be a propitious time for eternal truths. The more we learn, the weirder it will get. Hang on to your hat. That may be all you’ll be able to hang onto.

Thinking, Feeling, Wanting

Wait! I’m thinking in German!

Yesterday, Suellen and I went to our yoga class, just like every other Monday morning for the past three years. We enjoy the class and especially like our teacher, Natasha. Unfortunately, Natasha wasn’t there.

Natasha had been called away on short notice so, without warning, we had a substitute. She swirled into the room, asking lots of questions about what we could and couldn’t do. Frankly, I wasn’t prepared and was a bit annoyed. Who was this person and why was she interrupting the routine that I was so comfortable with?

Though somewhat off balance, I thought about the three basic mental functions: thinking, feeling, wanting. Here’s how I was doing on each:

Feeling – I was feeling irritated and out of sync. My morning routine had been upset and I was barely even awake.

Wanting – I wanted Natasha to return and get things back to normal.

Thinking – I was thinking that the status quo was disrupted. Beyond that, I wasn’t thinking much. I was just feeling and wanting.

In my critical thinking class, we describe the thinking-feeling-wanting triad as our most basic mental functions. For me, feeling and wanting are deep down in the engine room of a big ship. The thinking system is the Captain’s bridge. When things are going well, the bridge controls the engine room.

Sometimes, however, the feeling/wanting system runs out of control and unhooks itself from the bridge. The engine room is running but nobody is steering the ship. Suellen calls this “getting your undies in a wad” and it’s a fairly common occurrence.

So, what to do when your undies are in a wad and the engine room is boiling over? (Yes, it’s a mixed metaphor). Too often we focus on what we’re feeling and wanting. The trick to regaining control is to return our attention to the thinking function. Feeling and wanting are about emotions, not about control. Only by returning to thinking can we regain a sense of control.

My go-to questions in such situations include, “Why am I feeling this way? Is it logical to feel this way? What assumptions am I making?” When I thought about these yesterday, my internal monologue went more or less like this:

I’m being biased. I don’t want anything to change. It’s the status quo bias. I like our Monday morning routine. It’s very comfortable. Change is uncomfortable. But it’s silly to be biased. Think about the opportunity. Change can be exciting. Get with the program.

I know that I’m describing a very minor disruption. Still, I think it’s instructive. The way to regain a measure of self-control is to understand the differences between feeling, wanting, and thinking. When your undies are in a wad, think about thinking.

By the way, we had a great yoga class.

(The engine room is better known as the limbic system. The bridge is the executive function. Just like the engine room and the bridge, the limbic system really is lower – physically and conceptually – than the executive function).

When Should You Name Your Baby?

University of Guanajuato

In 1980, Suellen and I moved to Mexico where I was invited to teach at the University of Guanajuato. A lovely mountain town about 200 miles northwest of Mexico City, Guanajuato is rich in history, culture, and tradition. It’s the heart of the Bajío, a broad, fertile region known as the breadbasket of Mexico. Graham Greene’s novel, The Power and The Glory, uses the Bajío as a backdrop.

My students were in their twenties and getting married and having babies. During our year in Guanajuato, Suellen and I were invited to any number of “baby welcoming” parties. About a month after a baby arrived, the parents would host a party to introduce the baby to family, friends, and neighbors. It was like being a very small debutante.

The parties were quite touching. Attendees took note of the fact that a new member of the community had arrived. We implicitly agreed to help the child grow and prosper. We also told stories, offered advice, and gave presents.

At many of the parties, the baby did not yet have a name. I often asked about this: “Why haven’t you named the baby yet?” The more-or-less standard response: “We’ve only just met him. We need to live with him for a while to learn which name fits him best.”

I sometimes noted that, in the United States, we typically named our babies well before they arrived. To which one of my students remarked, “No wonder you gringos are so screwed up. You all have the wrong names!”

So when should you name your baby? It was a question I had never considered before… and that’s the point here. A central tenet of critical thinking is that we should question our own assumptions. As the world has changed, have our assumptions changed as well? Are they still valid? Were they ever?

But how do you question your assumptions if you don’t realize that you’re making assumptions? I assumed that one should name a baby before it arrives. I never questioned it. Why would I? It’s the natural order of things, isn’t it?

So, how do you uncover your unknown assumptions? Here are a few things that have worked for me:

- Learn a new language – many assumptions are bound up in our language; especially the metaphors we use. Learn a new language and you’ll pick up new metaphors and identify hidden assumptions.

- Travel to a different country – paraphrasing Yogi Berra, you can learn a lot just by observing.

- Talk to people who aren’t like you – living in a diverse community (or working in a diverse company) helps you think more clearly. You probably won’t suffer from groupthink.

- Study history – it’s amazing what people used to think.

- Ask yourself a simple question – why do I think that?

Questioning your assumptions doesn’t necessarily mean that you should change them. You may find that they still work quite well. We didn’t change our baby naming assumptions, for instance. We named Elliot well before he arrived and he turned out just fine (I assume).

A Joke About Your Mind’s Eye

Here’s a cute little joke:

The receptionist at the doctor’s office goes running down the hallway and says, “Doctor, Doctor, there’s an invisible man in the waiting room.” The Doctor considers this information for a moment, pauses, and then says, “Tell him I can’t see him”.

It’s a cute play on a situation we’ve all faced at one time or another. We need to see a doctor but we don’t have an appointment and the doc just has no time to see us. We know how it feels. That’s part of the reason the joke is funny.

Now let’s talk about the movie playing in your head. Whenever we hear or read a story, we create a little movie in our heads to illustrate it. This is one of the reasons I like to read novels — I get to invent the pictures. I “know” what the scene should look like. When I read a line of dialogue, I imagine how the character would “sell” the line. The novel’s descriptions stimulate my internal movie-making machinery. (I often wonder what the interior movies of movie directors look like. Do Tim Burton’s internal movies look like his external movies? Wow.)

We create our internal movies without much thought. They’re good examples of our System 1 at work. The pictures arise based on our experiences and habits. We don’t inspect them for accuracy — that would be a System 2 task. (For more on our two thinking systems, click here). Though we don’t think much about the pictures, we may take action on them. If our pictures are inaccurate, our decisions are likely to be erroneous. Our internal movies could get us in trouble.

Consider the joke … and be honest. In the movie in your head, did you see the receptionist as a woman and the doctor as a man? Now go back and re-read the joke. I was careful not to give any gender clues. If you saw the receptionist as a woman and the doctor as a man (or vice-versa), it’s because of what you believe, not because of what I said. You’re reading into the situation and your interpretation may just be erroneous. Yet again, your System 1 is leading you astray.

What does this have to do with business? I’m convinced that many of our disagreements and misunderstandings in the business world stem from our pictures. Your pictures are different from mine. Diversity in an organization promotes innovation. But it also promotes what we might call “differential picture syndrome”.

So what to do? Simple. Ask people about the pictures in their heads. When you hear the term strategic reorganization, what pictures do you see in your mind’s eye? When you hear team-building exercise, what movie plays in your head? It’s a fairly simple and effective way to understand our conceptual differences and find common definitions for the terms we use. It’s simple. Just go to the movies together.