Cursed Without Cursive?

When preparing a speech, I encourage my clients to hand write their notes and scripts. There’s something about handwriting that helps you connect with your thoughts and themes. The technique is especially helpful when preparing slides for a speech. Rather than sitting down at a keyboard, start with a set of yellow sticky notes. Then write down your thoughts — one per page — and arrange the notes on a wall. You’ll think more clearly and connect thoughts more effectively. You’ll also create better slides, with less text and more flow.

When preparing a speech, I encourage my clients to hand write their notes and scripts. There’s something about handwriting that helps you connect with your thoughts and themes. The technique is especially helpful when preparing slides for a speech. Rather than sitting down at a keyboard, start with a set of yellow sticky notes. Then write down your thoughts — one per page — and arrange the notes on a wall. You’ll think more clearly and connect thoughts more effectively. You’ll also create better slides, with less text and more flow.

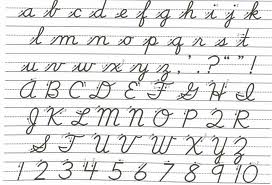

I never knew quite why handwriting worked so effectively. I just knew that it did. Then I stumbled across an article by William Klemm in Psychology Today about the importance of writing in cursive (as illustrated above). Klemm argues that learning to write cursive makes kids smarter. When learning cursive, “…the brain develops functional specialization that integrates both sensation, movement control, and thinking. Brain imaging studies reveal that multiple areas of the brain become co-activated during learning of cursive writing of pseudo-letters, as opposed to typing or just visual practice.” It also improves fine motor skills and gets kids to learn to pay attention more effectively.

Similarly, Susanne Baruch Asherson, writing in the New York Times, argues that “Cursive handwriting stimulates brain synapses and synchronicity between the left and right hemispheres, something absent from printing and typing.” Iris Hatfield, writing in New American Cursive, says there are ten reasons to learn cursive. Among them: increased speed, better fine motor skills, better self discipline, and improved self-confidence.

These articles are about teaching cursive to children. Do these benefits apply to adults? I encourage my clients to write drafts of their speeches (or press releases or white papers, etc.) by hand. I think most of them don’t take my advice — it just seems antiquated. But those that do, report positive results. Their communications are simpler and clearer. I also encourage my students to write drafts of their essays by hand. Again, most of them don’t take my advice. But I can generally guess which ones do. They turn in better papers.

So think about your communications. It’s a complex world and communicating effectively is a fundamental competitive advantage. Give cursive a chance. You may just find that you win more business.

Failed Business Fads: Top 10

Lucy Kellaway has an excellent column in the Financial Times in which she identifies the top 10 failed management fads. (Click here). Somehow the article reminded me of fashion fads, like Nehru jackets and leisure suits, that have come and gone. I sometimes cringe when I see old pictures of myself.

Lucy Kellaway has an excellent column in the Financial Times in which she identifies the top 10 failed management fads. (Click here). Somehow the article reminded me of fashion fads, like Nehru jackets and leisure suits, that have come and gone. I sometimes cringe when I see old pictures of myself.

I had to smirk at several of the management fads. I tried not to be my snarky, know-it-all self when the fads were in fashion but somehow I knew that they would never work. Now I have the warm satisfaction of knowing I was right all along.

There were, however, several fads that I actually believed in. In fact, I still do. So I’m distressed that Kellaway has declared them failures and asked us to bid them adieu.

I’m not tipping my hand because I’m interested in your opinions. Which of the fads have you experienced personally? Did any of them do any good at all? Is Kellaway right — are they all dead or do some of them still have legs?

Just leave your thoughts in the comments box below. In the meantime, I’ll be managing my employees by walking around them (or should I be walking them around?)

Appreciative Inquiry

When I encountered a problem as a manager, my natural inclination was to delve into it with sharply defined questions like:

- What went wrong?

- How did we get here?

- How did this happen?

- Who was responsible?

- What was the root cause?

The first thing you’ll notice about these questions is that they’re all in the past tense. As we know from studying rhetoric, arguments in the past tense are about laying blame, not about finding solutions. The very way that I phrase my questions lets people know that I’m seeking someone to blame. What’s the natural reaction? People become defensive and bury the evidence.

The first thing you’ll notice about these questions is that they’re all in the past tense. As we know from studying rhetoric, arguments in the past tense are about laying blame, not about finding solutions. The very way that I phrase my questions lets people know that I’m seeking someone to blame. What’s the natural reaction? People become defensive and bury the evidence.

The second thing you’ll notice is that all my questions are negative. The questions presuppose that nothing good happened. I don’t ask about what went right. I’m just not thinking about it. And neither is anyone else who hears my questions.

In many situations, however, a lot of things do go right. In fact, I would guess that in most organizations most things go right most of the time. Failures are caused by a few things going wrong. It’s rarely the case that everything goes wrong. Focusing on what’s wrong narrows our vision to a small slice of the activity. We don’t see the big picture. It’s self-defeating.

So, I’ve been looking for a systematic way to focus on the positive even when negative things happen. I think I may have found a solution in something called appreciative inquiry or AI.

According to Wikipedia, appreciative inquiry “is based on the assumption that the questions we ask will tend to focus our attention in a particular direction.” Instead of focusing on deficiencies, AI “starts with the belief that every organization, and every person in that organization, has positive aspects that can be built upon.” AI argues that, when people “in an organization are motivated to understand and value the most favorable features of its culture, [the organization] can make rapid improvements”.

The AI model includes four major steps:

- Discover – identify processes and cultural features that work well;

- Dream – envision processes that would work well in the future;

- Design – develop process that would work well in the culture;

- Deliver – execute the proposed designs.

The ultimate goal is to “build organizations around what works, rather than trying to fix what doesn’t”.

Paul Nutt compares appreciative inquiry to solving a mystery. To get to the bottom of a mystery, we need to know about everything that went on, not just those things that went wrong. Nutt writes that, “A mystery calls for appreciative inquiry, in which skillful questioning is used to get to the bottom of things.”

I’m still learning about appreciative inquiry (and about most everything else) and I’m sure that I’ll write more about it in the future. In the meantime, if you have examples of appreciative inquiry used in an organization, please let me know.

Proving Praise Is Not Productive

This will improve your performance.

Here’s a little experiment for your next staff meeting. All you need is an open space about ten feet long and maybe three feet wide, two coins, and a flip chart.

Once you’ve cleared the space, set a target on the floor at one end of the ten-foot length. The target can be a trashcan, a book, a purse … anything to mark a fixed location on the floor.

On the flip chart, write down four categories:

- P+ — praise works; performance improves

- P- — praise doesn’t work; performance degrades.

- C+ — criticism works; performance improves

- C- — criticism doesn’t work; performance degrades

Now have one of your colleagues stand at the end of the ten-foot space farthest away from the target and facing away from it. Give her the two coins. Ask her to take one coin and throw it over her shoulder, trying to get it as close as possible to the target.

Observe where the coin lands. If it’s close to the target, praise your colleague lavishly: “That’s great. You’re obviously a natural at this. Keep up the good work.” If the coin falls far from the target, criticize her equally lavishly: “That was awful. You’re just lame at this. You better buck up.”

Now have your colleague throw the second coin and observe whether it’s closer or farther away from the target than the first coin. Now you have four conditions:

- You praised after the first coin and performance improved. The second coin was closer. Place a tick in the P+ category.

- You praised after the first coin and performance degraded. The second coin was farther away. Place a tick in the P- category.

- You criticized after the first coin and performance improved. The second coin was closer. Place a tick in the C+ category.

- You criticized after the first coin and performance degraded. The second coin was farther away. Place a tick in the P- category.

Now repeat the process with many colleagues and watch how the tick marks grow. If you’re like most groups, Category 3 (C+) will have the most marks. Conversely, Category 1 (P+) will have the fewest marks.

So, we’ve just proven that criticism is more effective than praise in improving performance, correct? Well, not really.

You may have noticed that throwing a coin over your shoulder is a fairly random act. If the first coin is close, it’s because of chance, not talent. You praise the talent but it’s really just luck. It’s quite likely – again because of chance – that the second coin will be farther away. It’s called regression toward the mean.

Conversely, if the first coin is far away, it’s because of chance. You criticize the poor effort but it’s really just luck. It’s quite likely that the second coin will be closer. Did performance improve? No – we just regressed toward the mean.

What does all this prove? What you tell your colleagues is not the only variable. A lot of other factors – including pure random chance – can influence their behavior. Don’t assume that your coaching is the most important influence.

However, when we do studies that control for other variables, praise is always shown to be more effective at improving performance than criticism. I’ll write more about this soon. Until then, don’t do anything random.

(Note: I adapted this example from Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow. I think Kahneman may have adapted it from Edwards Deming’s experiment involving a fork and different colored balls.)

My Klout Is Growing

I’m happy to report that my Klout has grown 430% since I first began monitoring it in October 2011. Clearly, I’m an influential guy.

I’m happy to report that my Klout has grown 430% since I first began monitoring it in October 2011. Clearly, I’m an influential guy.

Klout is an application that purports to measure how influential I am in the world of social media. It’s based on the two-step theory of mass communication. In step one, a mass marketing campaign influences a relatively small number of people. Let’s call them the target audience. In step two, members of the target audience reach out to their social circles and influence them.

Let’s say you’re trying to recruit volunteers to work for a political party. You launch a massive advertising campaign. A lot of people see the campaign but only a few are moved to action. These people, however, through their web of friendships and acquaintances, can move a much larger number of people.

Unfortunately, you pay for the total number of people who see the campaign, not the (much smaller) number of influential people. Wouldn’t it be nice if you only paid for reaching influential people? The question is: how do you find them?

That’s where Klout comes in. Klout measures my impact in social media. It tracks what I do on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, LinkedIn, and a few others. It notes how many followers and friends I have. It also tracks my impact. It’s good to have a large number of followers and friends. It’s even better when those followers “like” my posts, forward my articles, and re-tweet my tweets.

The result of all this counting and measuring is a Klout score that ranges between zero and 100. The higher the score, the more influential you are. The higher the score, the more valuable you are to advertisers.

Remember that we’re talking about social media here – not influence in the real world. Thus, it’s not too surprising that Justin Bieber’s Klout score is 100 whereas Barack Obama’s is 88. President Obama can move people. Bieber can move merchandise.

Klout doesn’t “sell” high scoring individuals to advertisers. It’s a bit more subtle. It uses “perks” to attract people to sign up and to link them marketers.

When I first registered with Klout, my score was 10. That’s pathetic and no advertiser wanted to connect with me. As I’ve built my social media empire, my Klout score has risen to a much more respectable 53.

Now advertisers are interested in me. They want to give me “perks” that will keep their products at the top of my mind. In fact, I just cashed in a perk and received a free subscription to Red Bulletin, a splashy magazine published by the energy drink, Red Bull.

The makers of Red Bull seem to believe that, if I read Red Bulletin, I will exercise my massive influence and cause my circle of social media friends to drink more Red Bull. I’m not sure that’s going to happen. By and large, the people I influence are just not in the Red Bull demographic. Perhaps the makers of Geritol would be better served by “perking” me.

I’m going to keep track of my Klout score largely because I use it in my marketing classes. I’ll report on it every now and then. I hope you’ll help me keep my Klout score high by “liking” my posts and re-tweeting my tweets. Of course, you could also buy some Red Bull.