Delivering Student-Centric, Best-of-Breed Education

Passport to Education

So, how do we deliver student-centric, best-of-breed education? It’s a worthy goal and I think three things have to happen. Here they are … I’d love to hear what you think as well.

1) Develop the student passport – if education is invested in the student rather than the institution, we’ll need a way to track what students are doing over time. I think of it as a passport, in three different ways: 1) It’s kept by the individual rather than the institution. 2) It’s universally recognized. 3) It keeps track of all the individual’s educational experiences.

On the other hand, it’s probably not a physical booklet but rather an online system. The student is responsible for keeping it up to date and can choose to give access to it (or not) to educational institutions, potential employers, potential spouses, and so on.

2) Agree on the competency required – let’s say a student acquires a number of educational experiences and claims that the sum of those experiences is equivalent to an MBA. To decide whether the claim is accurate, we first need to have some agreement on what constitutes an MBA.

That may sound difficult to achieve but we’ve already made a lot of progress. Different schools may have different emphases but accrediting agencies have a sense of what the common competencies are. Indeed, we now have a vision of a Common Core Curriculum for public education in the United States – and that was certainly a politically fraught process. Deciding what competencies constitute an MA or and MBA or a Ph. D. should be simple by comparison.

Notice that I emphasize “competency” rather than “curriculum”. Schools today may teach the same curriculum but some teach it well and some teach it poorly. We get by with a rough-and-ready sense of the prestige of the institution granting the degree. For instance, we might value a degree from Stanford more than a degree from Princeton. But that’s a very slippery yardstick and a student-centric universe would value what’s in the student more than what’s in the institution.

3) Universal testing, certification, recognition – if we focus on competencies rather than curricula, we’ll also need some method to test and certify that a given student has a given competency. We already have this in professions like law, medicine, and architecture. In a student-centric world, we would extend the model to other disciplines and professions. Indeed, I’ve always wondered why we need to test and certify architects but not, say, captains of industry.

We already have a number of testing agencies at the national level. For instance, Educational Testing Services (ETS) administers admission exams such as the SAT and GRE in the United States. ETS seems to be well positioned to test other competencies the domestic market. I would argue, however, that the testing should be global rather than national. At the moment, I don’t see an institution that’s ready to take on a global role.

So there you have it. Just three small steps to flip the educational model and put the student at the center of the universe. Can we do it? Well, we’ve already done it with wine. More on that tomorrow.

Best of Breed Education

Baby Talk – Competency Level 1

When Elliot was a teenager, he went off to a weeklong sailing course approved by the Royal Yachting Association (RYA) in Britain. He passed with flying colors and received an International Certificate of Competence as a Sailing Crew Member – Level 1. The certificate attests to one’s “ability and provides documentary assurance from one government to another that the holder meets an agreed level of competence….”

With his certificate in hand, Elliot could serve on any sailing crew that requires Level 1 competency. He could also take his certificate to any other RYA-approved sailing school and immediately enter the course to achieve Level 2 competency. He could choose the next sailing school based on schedule or location or teacher or whatever. Not only does Elliot know something but his knowledge is also certified in a manner that’s globally recognized. That means he has a wide array of choice and options – he’s a free agent.

Why couldn’t higher education work the same way? Why can’t we flip the educational model to make it student-centric? Why can’t a student accumulate knowledge from a variety of sources and then have it certified in a globally recognized manner?

For instance, my online students at the University of Denver clearly want to acquire knowledge that will afford them broader skills and opportunities. Some are pursuing knowledge for the sake of knowledge. But many students also want that knowledge to be certified. Since the University grants the certification, students are incented to take courses only from one institution. It’s an institution-centric system.

Now the University of Denver is a great school but why couldn’t one of my students – perhaps living in Montana – also take online courses from New York University and the University of Toronto and the London School of Economics plus some on-campus courses at Montana State and have it all count toward a Master’s degree? In fact, why couldn’t she also acquire knowledge from workshops offered by the local Chamber of Commerce or a chapter of the Project Management Institute and also have that knowledge count toward a degree?

Why couldn’t she bundle it all together and have it certified as the equivalent of an MBA? We can certainly imagine that courses from multiple sources might offer a richer, more varied, and perhaps higher quality education. Every university has some good teachers and some not so good teachers. Why not select the best teachers and best courses from multiple institutions rather than taking all courses from only one school? Let’s call it best-of-breed education.

To deliver student-centric, lifelong, best-of-breed education, we’ll need to develop several new processes and agencies. The good news is that several of them are already under way. Let’s talk about them tomorrow.

Popping The Filter Bubble

Let’s say that I’m a vocal and vehement advocate of a flat tax. I’m adamant that implementing a flat tax will solve all the world’s problems. I read widely on flat tax theories … and I only read articles that agree with me. Why bother reading the opposite side? I already know they’re wrong.

Let’s say that I’m a vocal and vehement advocate of a flat tax. I’m adamant that implementing a flat tax will solve all the world’s problems. I read widely on flat tax theories … and I only read articles that agree with me. Why bother reading the opposite side? I already know they’re wrong.

What could be wrong with this? Well, two things. First, it could lead to dementia. The theory is that reading things that I agree with only reinforces existing connections in my brain. It doesn’t create new connections. Creating new connections seems to be a good way to forestall dementia. So, reading contrary opinions may lead to improved brain health.

Second, reading only things I agree with could lead to more extreme positions and greater animosity between people of different political convictions. The body politic polarizes. Does that sound familiar? Can we blame it all on the Internet? Maybe.

Now let’s extend the example. Let’s say that I use a search engine to find new articles about flat taxes. Let’s also assume that the search engine is smart enough to recognize that I only select articles that are positive about flat taxes. So, the search engine does me a “favor” and only presents positive articles. Not only do I not read contrary opinions, I’m not even aware that such opinions exist. Further proof that I must be right!

Several years ago, Eli Pariser coined the term “the filter bubble” to describe this phenomenon. Pariser argues that we live in bubbles that filter out important information, including information that would counter our opinions. (I typically use the term “echo chamber” for the same effect).

To my way of thinking (which may be filtered), this is a serious problem. Fortunately, according to a recent article in Technology Review, there may be ways to build recommendation engines that expose people to contrary ideas in such a way that they receive them with reasonably open minds.

Researchers in Barcelona built an engine based on the “idea that, although people may have opposing views on sensitive topics, they may also share interests in other areas. [The] recommendation engine … points these kinds of people towards each other based on their own preferences.”

According to the researchers who designed the engine, ““We nudge users to read content from people who may have opposite views … while still being relevant according to their preferences.”

The engine creates a “data portrait” for users and compares them. Users who have similar data portraits except for the “sensitive issue” (the flat tax, in our case) are connected to each other. They find that they share many interests even though they’re on opposite sides of the sensitive issue. However, because there is some common ground, the people are more willing to listen to each other.

It seems like a promising start and I’m going to try to use the recommendation engine to see what my data portrait looks like. I’ll report results as soon as I can. In the meantime, you can the original research article here.

Don’t Call Me Surely

Surely, this isn’t happening

I’ve written before about mental shortcuts called heuristics – rules of thumb that help us make a great majority of our decisions. Most of the time they work brilliantly. We recognize patterns subconsciously and make smart decisions automatically. Our conscious brain is free to deal with more difficult tasks. It’s like automatic pilot or highway hypnosis.

While heuristics help us get through the day, they can also make serious mistakes. (For a catalog of mistakes, click here, here, here, and here). It’s a fairly long list and surely most of us have made most of them. The more we’re aware of our heuristics, the more we can teach ourselves to avoid the errors inherent in automatic thinking. We can learn how to not trick ourselves.

But what about when someone else tries to trick us? Just like heuristics, the tools of disputation can lead us to believe things that just aren’t true (or disbelieve things that are true). You can always look to the evidence but you may be presented with evidence that’s biased or simply wrong. However, just as you can learn to recognize the ways that you deceive yourself, you can also learn to recognize the ways others deceive you.

Peter Facione can identify 17 ways in which our own heuristics can deceive us. On the other hand, Richard Paul and Linda Elder can identify 44 “foul ways to win an argument”. Surely the fact that there are so many more ways to deceive others (as opposed to ourselves) indicates that humans are innately devious. We’re not to be trusted.

Over time, I plan to catalog all 44 methods of deception so we can compare the ways we trick others to the ways we trick ourselves. I wonder which causes which. Do others deceive us or do they simply confirm our own self-deceptions?

So, where to start? Well, I’ve already slipped the first one by you. It’s what I call the handily hidden assumption and is often preceded by the word “surely”. When a person says, “Surely you believe…” or “Surely we can agree…”, it’s time to suspect trickery. The person is trying to hide an assumption so you won’t question it. The conclusion may flow logically from the assumption, but the assumption may be fatally flawed. If you ignore the assumption, the argument may sound logical and convincing.

In logic, this is known as begging the question. In common parlance, we often use begging the question to mean raising the question. In fact, however, it means exactly the opposite. It really means that the question goes begging. The question of whether the assumption is correct goes begging. Nobody pays it the respect it deserves.

So be careful when you’re debating a point with a slippery sophist. Or, for that matter, when you’re reading my website. And don’t call me surely.

Disgustology

My mother used to say that good manners are like oil in an engine. If you have them, everything runs more smoothly.

My mother used to say that good manners are like oil in an engine. If you have them, everything runs more smoothly.

But is that all that manners are good for? Valerie Curtis, who might be called the Doyenne of Disgust, writes that manners evolved because we’re so… well, disgusting.

Curtis argues that one of the benefits of being a human is that we’re a very cooperative bunch. By collaborating with each other, we can accomplish great things. But only if we don’t die first. Curtis describes us as a “walking bag of microbes”. My microbes are probably not good for you and vice-versa. So we need to learn to keep our distance.

Curtis writes that manners are fundamental to human nature and evolved from two related systems. The first is the “disgust system, which motivates us to recognise and avoid potential pathogen hot zones.” The second is “the ability to feel shame.” Curtis surmises that feeling “shame if someone looks at us with a disgusted expression” is simply nature’s way of moderating our behavior to keep us from infecting one another.

Manners may have evolved to help us avoid diseases but they also helped us develop complex social systems. Curtis writes, “Humans became adept at looking for clues as to who was likely to cooperate and who was not. Manners provided an indicator. Those who were careful with hygiene were good candidates, as were those who put … the interests of others before themselves.”

While Curtis has a new book out on disgustology, the field has been growing for the past several decades. Other contributors include Daniel Fessler, Jonathan Haidt, Rachel Herz, Daniel Kelly, Paul Rozin, and Joshua Tybur Here are some key discoveries form their work:

It’s not all oral – different researchers proposed different typologies of disgust. Some suggest that there are nine different domains of disgust; others identify only seven. We might immediately identify disgusting smells and tastes. But we’re also disgusted by fleas and immoral behavior. The world is disgusting in many ways.

Liberals and conservatives view disgust differently – research suggests that liberals and conservatives are similar when it comes to the disgust of disease avoidance and immoral behavior. But conservatives are more disgusted by sexual topics.

Pregnant women are more sensitive to disgust – researchers found that, as progesterone levels increase, so does sensitivity to disgust. This seems particularly true in the first trimester, when the immune system is weakened. Apparently, our bodies protect us from low immunity by increasing our sensitivity to disgust.

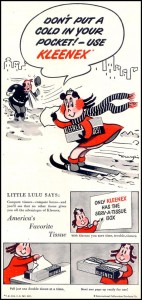

It works in advertising — though it hasn’t been studied formally, I can attest that disgust can create powerful advertising and branding campaigns. The Little Lulu illustration above is from a famous campaign that changed our behavior. Prior to Little Lulu’s warning – Don’t Put A Cold In Your Pocket — people often carried cloth handkerchiefs. They sneezed into them and then returned the handkerchief to their pocket. Ewww! If you don’t carry a cloth handkerchief today, you can thank Little Lulu.

Apparently, some of our campaigns have come full circle. Little Lulu changed our handkerchief behavior. Valerie Curtis aims to change out bathroom behavior — and wash our hands more often — with a campaign build around the slogan, Don’t Bring the Toilet With You. If it works as well as Little Lulu, we could all be cleaner and healthier.

(The Little Lulu ad comes from the Gallery of Graphic Design).